100 Times (A Memoir of Sexism), by Chavisa Woods [Seven Stories Press]

In 100 Times (A Memoir of Sexism), Chavisa Woods chronicles the systematic sexism and gender oppression she’s experienced over the course of her life. From childhood chidings, to work-based gender inequality, to unsolicited groping, to harrowing accounts of toxic masculinity and rape, Woods’ text pinpoints the pervasive threat that is institutionalized sexism. Regardless of a woman’s age, location, gender performance or any other type of cultural condition, Woods reiterates the threat is inescapable and, hence, completely relatable.

Yet Woods refuses to be victimized. Several of her memories are underscored by consciousness-raising and the development of individual agency. Her experiences are multifaceted yet relatable, her writing is conversational and responsive. As such, 100 Ways is the perfect tool for inciting the rage needed to subvert gender inequality. – Elisabeth Woronzoff

Read more about this book here PopMatters.

’68: Mexican Autumn of the Tlatelolco Massacre, by Paco Ignacio Taibo II [Seven Stories Press]

Paco Ignacio Taibo II has been called Mexico’s “de facto minister of culture”. A literary icon with over 80 books to his name, he was recently appointed director of the Mexican government’s national publishing house, Fondo de Cultura Economica – a move which has been described as akin to “a somewhat younger Noam Chomsky being appointed US Secretary of State.”

Five decades ago, in 1968, he was cowering in a tiny room with a poster of Tokyo’s Ginza district on the wall, unable to sleep for fear the Mexican army would burst into the house and arrest him. His fears were shared by hundreds of thousands of other Mexican students – the ones who hadn’t already been arrested or murdered by the army, that is. In the wake of a tremendous 123-day long student protest movement for democratic reforms, crushed only by the gunfire of Mexican soldiers and the arrest and torture of thousands of activists, Taibo was fortunate to have miraculously avoided either fate. ‘68: The Mexican Autumn of the Tlatelolco Massacre, is a powerful reminder of the resilience of democracy. – Hans Rollmann

Read more about this book here on PopMatters.

American Carnage: On the Front Lines of the Republican Civil War and the Rise of President Trump, by Tim Alberta [HarperCollins]

Many books have already been written trying to determine just what the hell has been going on with Republicans in America the last few years. The problem is, many of the books have been written by, if not outright liberals, then people without an insider’s take on the conservative movement. While American Carnage is not necessarily a great political book, it is probably one of the most necessary of the past few years, given former National Review writer Tim Alberta’s ability to embed himself in the GOP’s nerve center.

Beginning with the revolt that almost killed TARP—the financial relief bill thrown together to head off the Great Recession, Alberta tracks with precision and wry irony the party’s spiraling descent into today’s Fox News-enabled know-nothingism. The devolution of the conservative movement into nihilism is rendered with vivid detail and a kind of sickening dread as the avatar of this chaos, Donald Trump, takes control of a party whose leadership does little or nothing to stop it. Alberta keeps his judgement to the side mostly, but for a few sharp jabs of the knife, such as the description of Paul Ryan’s “deal with the devil” (not criticizing Trump in exchange for his long-wanted tax cuts) as being one he “did not think twice about making.” – Chris Barsanti

A Beginner’s Guide to Japan, by Pico Iyer [Alfred A. Knopf]

Finding a feeling of belonging in a place is a theme in Iyer’s work, as his life is one of perpetual dislocation. Iyer’s observations and provocations are packaged in spare but descriptive prose, so fitting for the minimalist tradition in Japanese art and literature. – Linda Levitt

Read more about this book here on PopMatters.

Angry Queer Somali Boy: A Complicated Memoir, by Mohamed Abdulkarim Ali [University of Regina Press]

Mohamed Abdulkarim Ali’s Angry Queer Somali Boy is a harrowing read, a blunt hammer of a book which holds nothing back in its graphic depiction of racist violence and sexual abuse. It would be easy to feel a combination of deep pity and profound respect for its author, but a more appropriate emotion to feel would be shame on behalf of the society which makes such stories possible; and even worse, common. It’s a harrowing read, but a vitally important one.

If white folks wish to be woken from their stupor and understand the ways in which their societies cultivate the sustained ruin of the lives of non-white refugees and immigrants, this book will do it. It’s a masterpiece of memoir, but also a cultural critique of the first order. Ali’s is an angry, queer Somali voice that has a great deal of important things to say and says them in wise, compelling prose. It is a voice that North America urgently needs to hear more of. – Hans Rollmann

Read more about this book here on PopMatters.

Be With Me Always, by Randon Billings Noble [University of Nebraska Press]

Randon Billings Noble’s Be With Me Always is a tender, graceful collection of essays from a writer whose mission seems clear. Who are we within the context of our desires and longings? How do we function within bodies that are regularly changing? Through the process of viewing ourselves outside the shell of our beings, Noble does not seem to be suggesting that we can or even should live outside the limits of our corporeal essence, but we can try.

Reading these essays is tantamount to dancing between lines of longing, looking without seeing, constructing and deconstructing our very essence, and understanding that nothing is really ever as it seems unless and until we see it again, with a fresher and sharper perspective. – Christopher John Stephens

Read more about this book here on PopMatters.

Belonging, by Nora Krug [Scribner / Simon & Schuster]

Where some contemporary comics drop tantalizingly big ideas but fail to follow through with sufficient thoroughness to do their subjects merit, Nora Krug’s work lies at the opposite end of the spectrum. In graphic memoir Belonging, she takes a single idea – her family’s involvement in the Second World War – and pursues it with relentless, forensic determination.

Krug’s forensic reconstruction of her family history, and the history of the city of Karlsruhe, in which they lived, is remarkable. Through repeat visits to Germany, archival research, interviews with surviving relatives and townsfolk, she helps to paint a picture of what life was like during the Nazi period and the difficult choices people had to make. For better or for worse, she inserts her own judgement into the picture: this is what renders the book both so personally compelling as well as so provocative. – Hans Rollmann

Read more about this book here on PopMatters.

BlackLife: Post-BLM and the Struggle for Freedom, by Rinaldo Walcott & Idil Abdillahi [ARP Books]

In Black Life two academics based in Toronto – Rinaldo Walcott and Idil Abdillahi – offer a series of powerful and important reflections on the present state of the Black Lives Matter struggle in Toronto, and by extension Canada as a whole. They take to task Canada’s recurring sense of “surprise” and “wonder” at the Black presence in the country, both past and present. This sense of surprise and wonder is a deliberate construction: not only profoundly inaccurate, it is also central to the country’s sustained origin myths and to the sustaining centrality of white power.

Black Life: Post-BLM and the Struggle For Freedom is a short volume, but one of the most important intellectual interventions to emerge in Canada in recent years. It ought to be required reading in Canadian Studies and other social science and arts courses at both secondary and post-secondary levels across the country. Above all, it ought to be taken seriously by those – especially white Canadians – with the ability to apply its insights in public policy and private lives alike. – Hans Rollmann

Read more about this book here on PopMatters.

The Book of Sarah, by Sarah Lightman [Pennsylvania State University Press]

While the art world is full of excellent artists, few have the comics savvy to construct the sort of complex narratives and image-text relationships that Sarah Lightman achieves in her graphic memoir, The Book of Sarah. Each of Lightman’s eight chapters feature a Torah-related title, emphasizing the religious focus of her upbringing—one that resulted, directly or indirectly, in her suffering decades of anxiety and insecurity. Or maybe she would have suffered the same if she had grown-up in another religion or in none at all.

Lightman seems to be more than one person—or rather herself at different moments in her evolving life. Her self-portraits and varying styles capture this effect, but her verbal narration emphasizes it too. Still, the absence of a biblical Book of Sarah speaks metaphorical volumes. – Chris Gavaler

Read more about this book here on PopMatters.

Cannabis: The Illegalization of Weed in America, by Box Brown [First Second / MacMillan]

As cannabis legalization spreads, Box Brown’s graphic non-fiction, Cannabis, examines the sordid and racist history of how it became demonized in the first place. He explores the process by which cannabis went from a harmless, and in many cultures sacred intoxicant and medicine, to a demonized drug in the early decades of the 20th century in America.

The story is an important reminder of how racism fuels moral panics, and how the so-called evidence used to justify both is often, predictably, falsified. There’s a certain jarring parallel to the falsification of research and sensationalization of fake news that led to cannabis illegalization, which will be all too familiar to contemporary readers. The way in which cannabis was framed by false research and emotionally charged testimonies that appealed to the worst in human nature is resonant of the way similar tactics are used by anti-abortion crusaders; the fact legislators succumb to their fake news and counter-intuitive arguments has an eerie parallel in the way legislators fell for the anti-cannabis crusades in the 1930s, despite all evidence and common sense. The fact that such tactics have become so pervasive, even up to the office of the President, offers a grim reminder that our society has not yet emerged from that fog which combines performative moralizing with self-serving ambition. – Hans Rollmann

Read more about this book here on PopMatters.

Crosby, Stills, Nash and Young: The Wild Definitive Saga of Rock’s Greatest Supergroup, by David Browne [Da Capo]

No one captures the magnetism, sheer insanity, blistering hope, and jaw-dropping anguish of the ’60s and ’70s quite like David Browne. A senior writer at Rolling Stone and the author of several music histories (including two must-read books about the late Jeff Buckley), Browne is one of the only writers who could gain unfettered access to those in and around the world of David Crosby, Stephen Still, Graham Nash, and Neil Young.

Crosby, Stills, Nash and Young is well-researched and driven by an intense focus for the smallest details. Browne pulls back the curtain on a truly “wild” saga; a saga of a supergroup that couldn’t stay together, but also couldn’t stand to be apart. Everything you ever wanted to know about CSNY is in these pages, for fans and non-fans alike. – Scott Elingburg

Dead Blondes and Bad Mothers: Monstrosity, Patriarchy, and the Fear of Female Power, by Sady Doyle [Melville House]

The chief delight of Dead Blondes and Bad Mothers is not that it presents any new information, but that it aggregates a pile of information we already know into a package that is pleasing. It’s pleasing because Doyle has an amusing voice. By “has an amusing voice” I mean “is possessed of a rage she has skillfully channeled into witty articulation”.

It’s rather difficult to keep propping up the patriarchy because the truth is that women are so very powerful. Men fear us, and so in their various creative, legal and familial discourses, we are constructed as monsters. The theory is not complicated, especially as it will dovetail so clearly with the lived experiences of the women who will read it, and the entire book is jargon-free. – Megan Volpert

Read more about this book here on PopMatters.

Dramatic Exchanges: Lives and Letters of the National Theatre, by Daniel Rosenthal [Profile Books]

Daniel Rosenthals’ Dramatic Exchanges offers an alternative history of the renowned National Theatre, one presented entirely through epistolary forms: the letters, cards, memos, telegrams, and emails exchanged by actors, directors, designers and other creatives involved in the theatre from the turn of the century to the present. The result is a lively, highly enjoyable collection that nicely complements not only Rosenthal’s previous book, The National Theatre Story, but also Hall and Eyre’s absorbing published diaries and Hytner’s memoir, Balancing Acts.

Dramatic Exchanges is a delightful, illuminating and sometimes surprising read. The bookstands as a multi-voiced tribute to the diverse artists who have shaped the National’s evolving story, and a testament to what Rosenthal calls the “moments of crisis, inspiration or jubilation when only writing will do” (p. xiii). – Alex Ramon

Read more about this book here on PopMatters.

EC Comics: Race, Shock & Social Protest, by Qiana Whitted [Rutgers University Press]

EC Comics was best known for breaking necks. Once their signature style became fully developed, it was all about building up expectations and then twisting them and smashing them. Scholar Qiana Whitted’s EC Comics: Race, Shock & Social Protest explores a different path in the publication’s history: their work with social justice stories and the resulting censorship in 1950s America.

EC was always boundary pushing, being an icon of blood and guts and gunshot wounds, but it was not the gore that saw them being pressured by comics code authorities and the senate, wherein they eventually gave up on comics and kept only MAD magazine: it was their thoughts on human rights. – Christopher Laird

Read more about this book here on PopMatters.

The End of Forgetting: Growing Up with Social Media, by Kate Eichhorn [Harvard University Press]

Culture and media critic Kate Eichhorn’s The End of Forgetting explores how relentlessly documenting young lives allows little room for the unfettered joys of imaginative freedom and perpetuates a seemingly endless state of childhood.

For generations, a person’s memory of their childhood has been shaped by the photo albums and home videos that parents create, along with the school projects and ephemera that get boxed up as keepsakes. These pictorial histories typically remain private, making it possible to leave the past behind and to even destroy the evidence, should you make that choice.

When those stories become broadly shared social media artifacts, forgetting your mistakes is rendered impossible: we cannot leave the past behind. This brings forth in today’s youth a pressing but unacknowledged ethical concern. – Linda Levitt

Read more about this book here on PopMatters.

The Goldblum Variations: Adventures of Jeff Goldblum Across the Known (and Unknown) Universe, by Helen McClory [Penguin Books]

It is not hyperbole to say that Helen McClory’s The Goldblum Variations is the best book I have read this year. It’s marketed as pop culture / humor, and more loosely as absurdist fiction. It’s also very fine hybrid poetry, or flash essays, or any other number of mixed genre labels that tote around the enormous yet unacknowledged baggage of being “experimental”. So we’ll keep it in our non-fiction list.

It’s utterly approachable for people who did not go to graduate school, to people who say they “don’t get” poetry, and even people—if such people exist at all—who don’t know or don’t like Jeff Goldblum. McClory has crafted a very fine, lushly sensitive, gently moving series of portraits of a cultural icon. Metatexually dazzling yet absurdly soothing, The Goldblum Variations will put a dent in your bad vibes. – Megan Volpert

Read more about this book here on PopMatters.

Good Enough: The Tolerance for Mediocrity in Nature and Society, by Daniel S. Milo [Harvard University Press]

In Good Enough, philosopher Daniel S. Milo argues that Darwinism has gone too far.Evolution by natural selection accounts for much of the world around us, Milo insists, but this utility has blinded us to the limits of the theory. In this bold but carefully reasoned thesis, Milo undermines a “selectionist dogma” that has solidified in science and culture alike. Milo insists that nature is full not of excellence but of mediocrity—not cut-throat competitive champions but merely the manifold forms of life that survive just well enough not to die.

In other words, rather than producing the best possible forms of life, nature simply comprises those forms that are “good enough”, that are sufficiently outfitted to get by despite any number of glaring deficiencies and excesses. As a ranging and even-handed polemic, Good Enough is an important intervention that boasts none of the mediocrity that Milo finds everywhere at work—or rather, asleep on the job—in the natural world. – Ben Murphy

Read more about this book here on PopMatters.

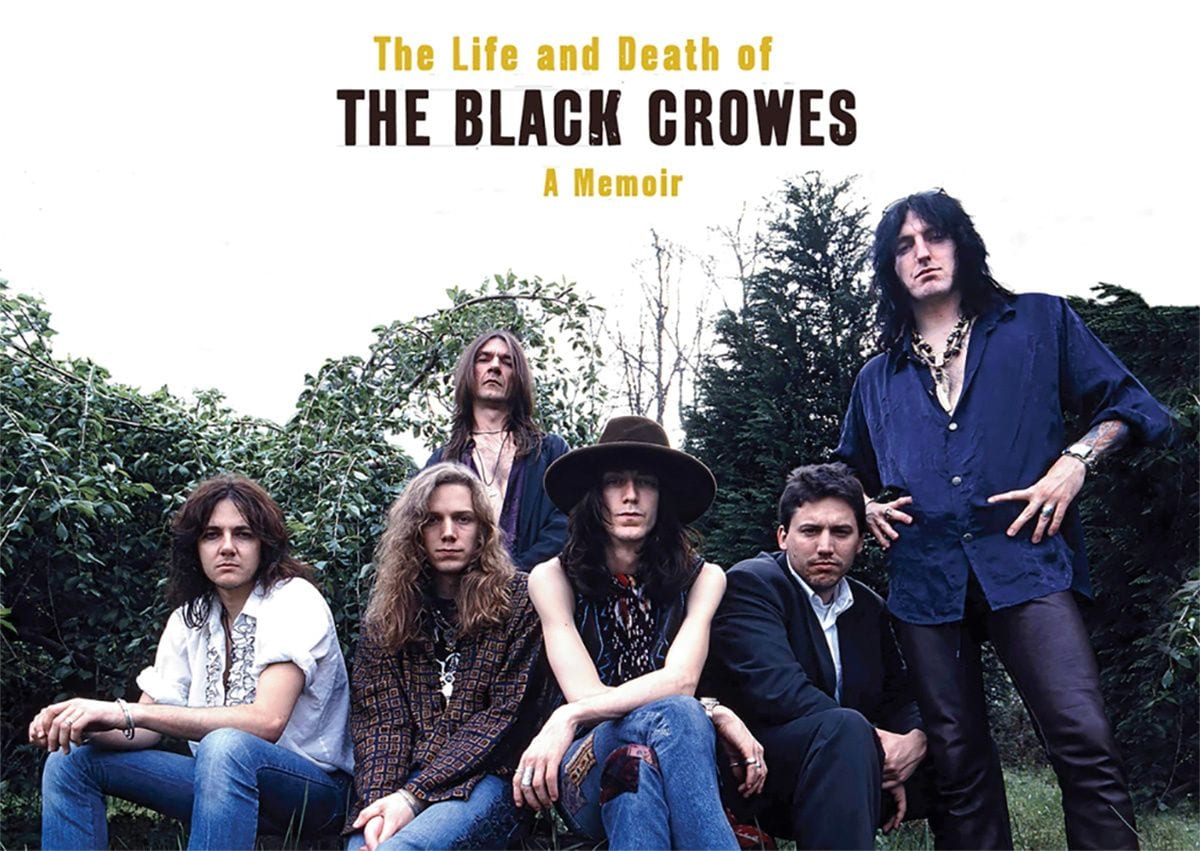

Hard to Handle: The Life and Death of the Black Crowes, by Steve Gorman [Da Capo]

Steve Gorman spent nearly all of his career as the drummer for rock band The Black Crowes. Now, he’s released a memoir for fans of the band, Hard to Handle, as a proper goodbye — because the Crowes never got around to a final farewell tour. Gorman is consistent and even-keeled when it comes to dishing dirt about the band and his role in it. There are way more positive vibes and tales of camaraderie than poisoned arrows in each chapter. Plus, there is a palpable feeling of brotherhood amongst members when the band is firing on all cylinders.

But, good Lord, when this band was a mess, it was a mess. Ego, poor decisions, drugs, alcohol, greed, women, more drugs and more alcohol drove The Black Crowes into a not-so early grave. The band did, after all, stay together for over twenty years and watching dozens of musical fads like hair metal, pop, grunge, boy bands, and indie rock, come and go. Props to Steven Hyden for sanding down some edges and helping shape all the information in this sordid tale. But this is 100% Gorman’s show. It’s his book, his life, and no one can tell this tale with as much heart as he does. – Scott Elingburg

High Heel, by Summer Brennan [Bloomsbury Academic]

The lovely cadences in Summer Brennan’s High Heel stack up like so many sand castles that sift iconic examples of high heels into a finely grained pile of pros and cons that each reader will sift through quite differently. The pain of the high heel is a given. So is the price of wearing them—and of not wearing them. Brennan resists giving way to easy judgments on either side. She’s inhabiting the same space as so-called “bad feminist” Roxane Gay, interrogating both sides of the high heel dilemma and refusing to declare a winner.

Whether you’re for them or against them, the radical uncertainty of Brennan’s take on high heels is worth reflection. – Megan Volpert

Read more about this book here on PopMatters.

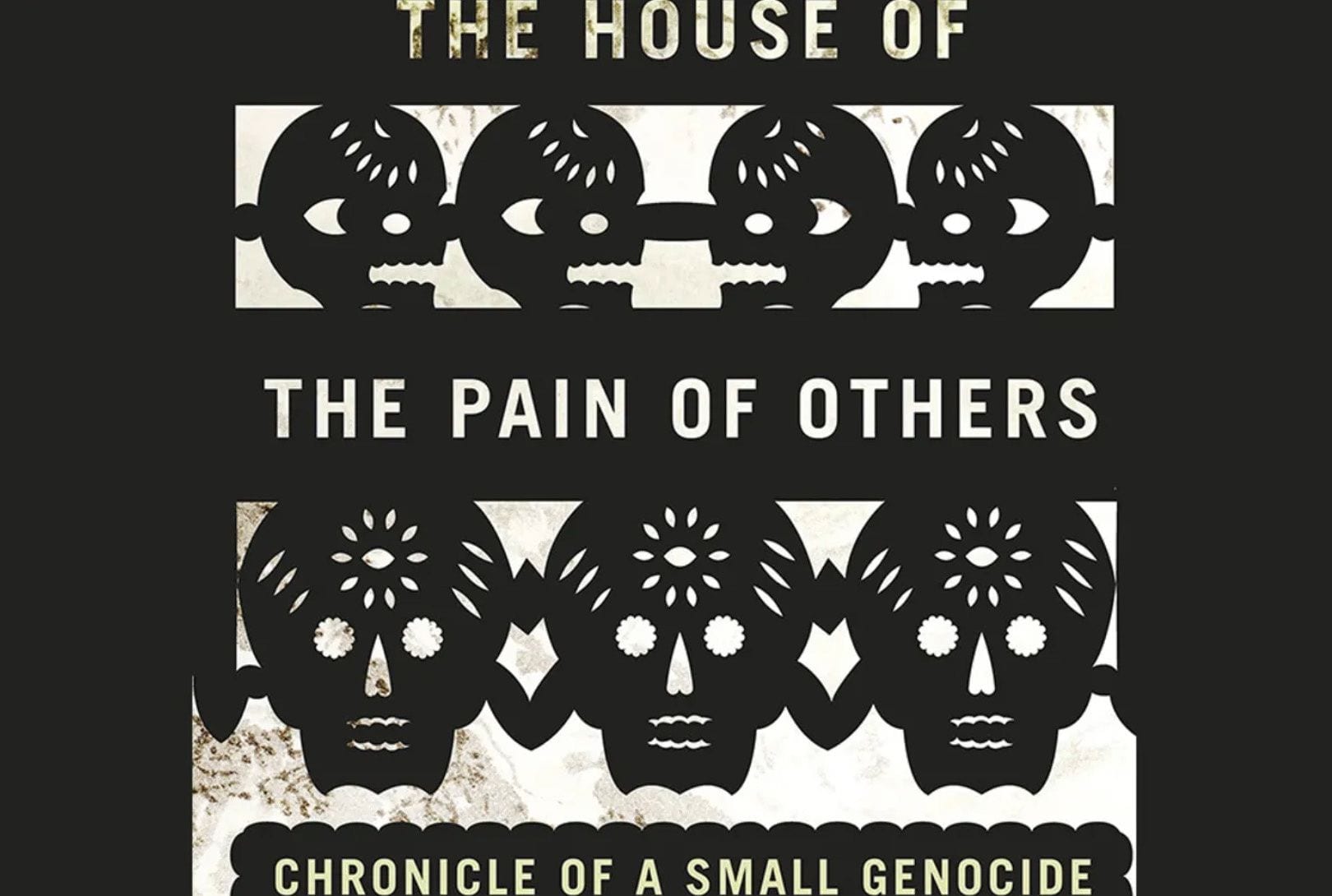

The House of the Pain of Others: Chronicle of a Small Genocide, by Julián Herbert [Graywolf Press]

The House of the Pain of Others is a masterly study that sheds light on the role played by educated elites in fomenting genocide.

Herbert’s book is a triumph: an eloquent testament not only to the hundreds of Chinese who were tragically slaughtered in the Mexican city of Torreón in 1911, but also a passionate, remarkable intellectual study in the psychology of racism. Herbert’s study is as much a history of the present as it is a history of the genocide of 1911. His research – thorough in its attention to minutiae, and impressive in its ability to draw on a range of theory, from Slavoj Žižek to Jorge Luis Borges – is complemented by a literary style which at times assumes near poetic qualities. – Hans Rollmann

Read more about this book here on PopMatters.

I Like to Watch: Arguing My Way Through the TV Revolution, by Emily Nussbaum [Random House]

In I Like to Watch, a collection of essays written by the Pulitzer Prize-winning television critic for The New Yorker, Emily Nussbaum’s writing is smart, quick-witted, and always engaging. Writing on all the prestige shows of the last decade or so, I Like to Watch takes a special interest in shows that tend to be dismissed as “guilty pleasures”, or “television for women” (e.g., The Good Wife, Jane the Virgin, Sex and the City, Law and Order: Special Victims Unit).

It’s no surprise that a book that begins with an essay on how Buffy the Vampire Slayer made her into a TV critic would go on to dissect and revel in the many ways television reflects our culture. In addition to series reviews and essays, there are interviews with Kenya Barris, Jenji Kohan, and Ryan Murphy. Of particular note is a previously unpublished piece on the #MeToo movement and the question of art vs. artist.

Nussbaum never lets herself off the hook in analyzing her own preconceptions and biases. She writes with irreverence and thoughtfulness throughout. – Jessica Suarez

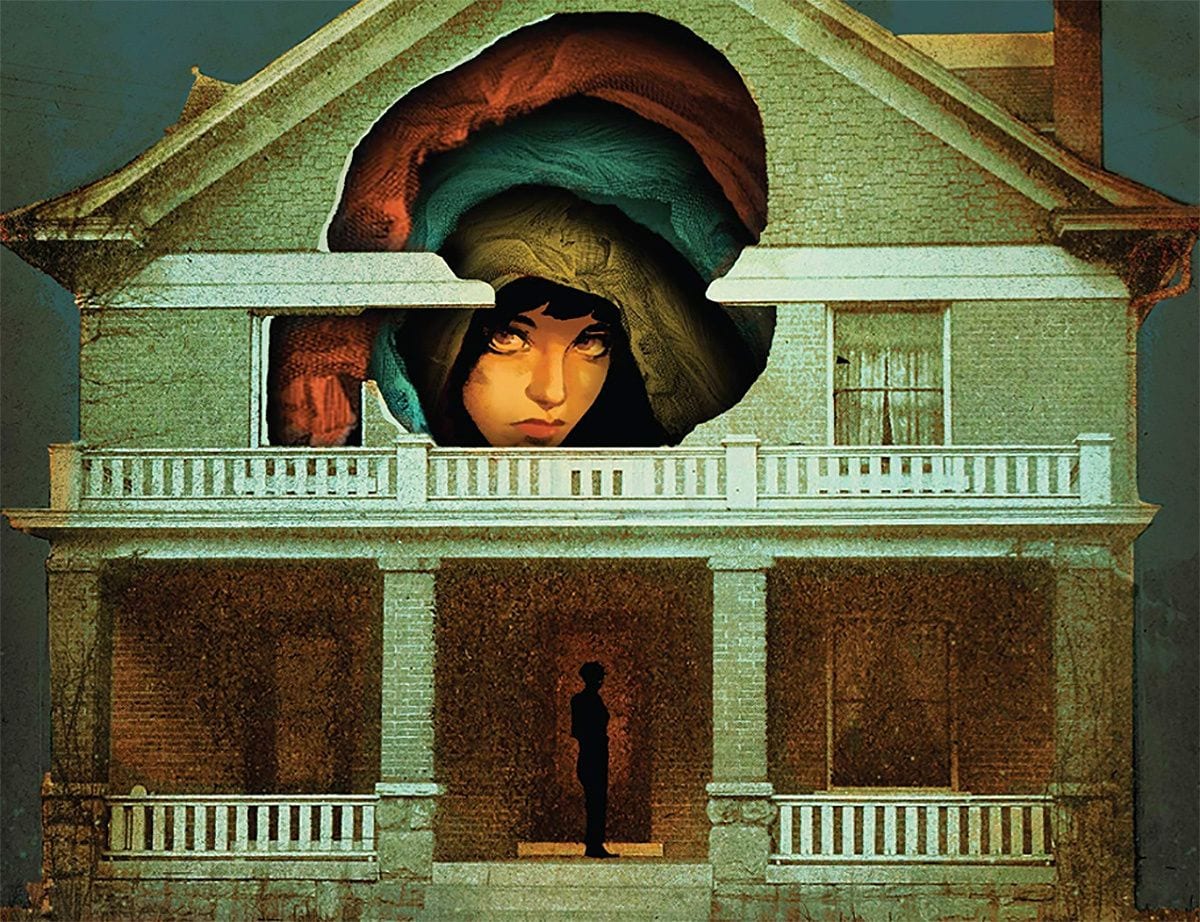

In the Dream House, by Carmen Maria Machado [Graywolf Press]

Folk tales, fantasy, pop culture and family weave gracefully throughout Carmen Maria Machado’s harrowing yet graceful memoir of domestic abuse, In the Dream House.

The only way to effectively process Carmen Maria Machado’s masterful and beautifully controlled memoir is to understand that this is one of the more ambitious, audacious, and successful experimental accounts of a journey from a house of horrors. It’s about so many things: a toxic relationship with an emotionally abusive girlfriend; a “choose-your-own-adventure” that proposes scenarios and likely outcomes; fairy tales’ a history of queer domestic abuse built on historical accounts and; connections between the author’s experiences and Stith Thompson’s Motif Index of Folk-Literature.

Despite the violence, the overall mood ofbis one of peaceful grace. Reflection from a safe distance. Machado captured our attention and earned our commitment from the first page and she never loses it. – Christopher John Stephens

Read more about this book here on PopMatters.

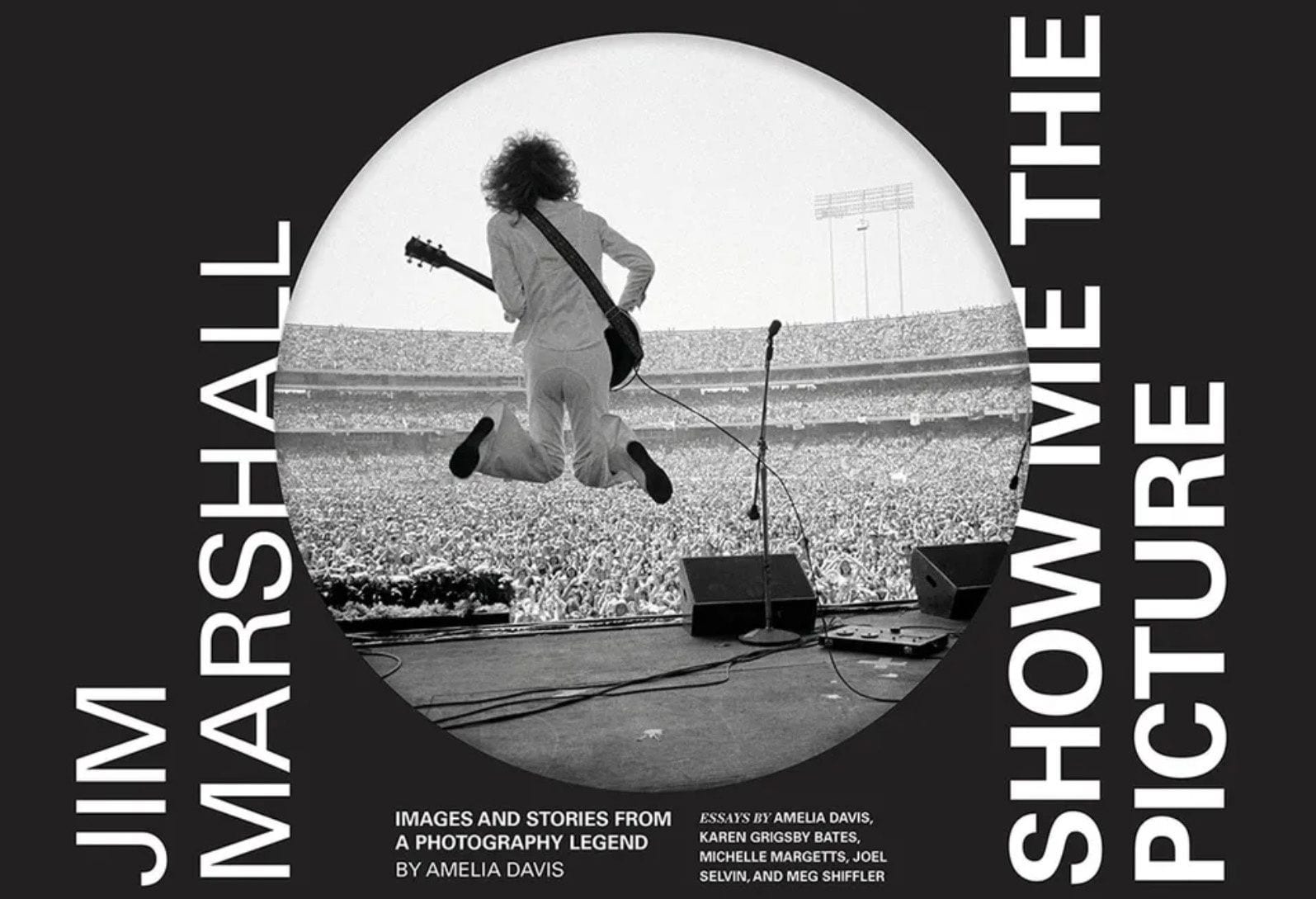

Jim Marshall: Show Me the Picture – Images and Stories from a Photography Legend, by Amelia Davis [Chronicle Books]

In Jim Marshall: Show Me the Picture, we get a full portrait of a master documentary photographer; a man who captured some stunning images at the early stages of the Civil Rights Movement and took that same sense of perspective from the Jazz festival and nightclub scenes of the early 1960s through that decade and into the next. here’s a 1982 photo of five plumbers standing in front of a Ford truck, laughing and relaxing. One of them notes: “We were plumbers, but Jim made us look like rock stars.”

Indeed, Marshall was perhaps best known for his photos of rock, jazz, and blues stars at work and relaxed. They’re sublime (John Coltrane) and routine (Led Zeppelin) but never boring. – Christopher John Stephens

Read more about this book (and enjoy photos) here on PopMatters.

JOANNA RUSS (MODERN MASTERS OF SCIENCE FICTION), Gwyneth Jones [University of Illinois Press]

Joanna Russ offers an insightful and learned account of Russ’s life and times. Gwyneth Jones traces Russ’s evolution from a repressed young woman coming to maturity in the suffocating atmosphere of the United States in the 1950s, through her first forays into both genre writing and feminism, to her emergence as one of sci-fi’s sharpest and most politically engaged critics and writers.

As Jones makes clear, Russ’s feminist politics were inseparable from her activities as a sci-fi writer and critic. What emerges is a portrait of a writer whose wit and intelligence is matched only by her fierce commitment to feminist politics. Jones’s masterly account of the life and times of Joanna Russ serves as a timely reminder of the strides made in visibility and diversity in science fiction literature —and the distance still left to traverse. – Thomas Connolly

Read more about this book here on PopMatters.

The Life of Saul Bellow: Love and Strife, 1965-2005, by Zachary Leader [Alfred A. Knopf]

The question Saul Bellow apparently asked at the end of his life is a fitting way to start this second volume of his biography by Zachary Leader, The Life of Saul Bellow: “Was I a man or was I a jerk?” It’s a fitting question to ask as we enter the world of late-1964 Bellow. Herzog has just been published. The novel, a masterpiece that blossomed from the end of his second marriage, carefully but without a doubt transposed the lives of ex-lovers and former friends into literary gold. By the time he turned 50, Bellow was famous from a book that took no prisoners and set the standard as to how that question might be answered. He was apparently a jerk who betrayed everybody and everything in his life but the work.

The question of whether or not somebody like Saul Bellow has been demoted from the canon will always be political. His work is not so frequently quoted as Philip Roth’s, John Updike’s, or John Cheever’s. Indeed, it can be clearly seen by the end of this book that while Leader might not be making a case for Bellow as the novelist of the century, he’s probably the emblematic white male novelist for his time, for better or for worse.

Leader provides more than enough material to give his reader a head start into a deep study of some important, challenging, controversial, brilliant, distinctly American literature.- Christopher John Stephens

Read more about this book here on PopMatters.

Making Comics, by Linda Barry [Drawn & Quarterly]

If you can’t take a class with Lynda Barry, Making Comics is the next best thing. But what kind of class is it? Making Comics is more than exercises. Barry provides her personal, free-form lectures too, taping in drawings by former students (some of them rescued from discards on the floor), to create as immersive a document as possible.

Making Comics is a love letter to every child who ever picked up a crayon and started making marks with unselfconscious intensity. Those children include Barry’s college students. Like her readers, some arrive at class with artistic training and some arrive with none at all. The latter arrive having long forgotten the uninhibited style of image-making they understood instinctively as children. Finding each of those children is Barry’s mission, and she is very very good at it. – Chris Gavaler

Read more about this book here on PopMatters.

Making Out, by Kathryn Bond Stockton [New York University Press]

Kathryn Bond Stockton’s Making Out is a wonderfully intense experience from start to finish. She knows we are primarily expecting the prurient aspects of her subject. We want to understand the intimacy of a kiss, the reasoning behind the action, but we also need to accept that (for Stockton) this book “…asks about reading.” For Stockton, reading “…is kissing and sex with ideas.” Why do we love the feeling of some words? The very act of kissing, she suggests, is “…strange, fertile, inefficient…related to reading, beautifully unknowable.”

Indeed, Stockton carefully spells out from the beginning that her text will include zones: “…memoir; conceptions; brief reflections on movies and books.” The reward for any reader of will rest purely in the success of our connection with the text; be it tenuous or full-throated and all-consuming (like a lethal kiss), it will depend on our willingness to engage with Making Out. – Christopher John Stephens

Read more about this book here on PopMatters.

Mass Exodus: Catholic Disaffiliation in Britain and America since Vatican II, by Stephen Bullivant [Oxford University Press]

Prolific young English scholar with a transatlantic perspective, Stephen Bullivant, follows up his sharp studies on atheism, unbelief, secularity, non-religion, and Catholic disaffection or re-affiliation with this sociological analysis. Trained in both theology and the social sciences, Bullivant blends the academic and journalistic approaches in his relevant research, as one of the leading interpreters of contemporary trends in religion.

In Mass Exodus, he takes on a subject dismissed by most of his colleagues. Rather than rehash tired cant about papal fallibility and conniving clerics, he analyzes data. His use of data and statistics, attesting to his dual appointment as a professor, enables him to appraise the impacts of Vatican II’s promises of reform, half a century later. What he finds may put paid to facile notions that progress always trumps tradition, and that change renews. – John L. Murphy

A Mind Spread Out on the Ground, by Alicia Elliott [Doubleday Canada]

Haudenosaunee writer Alicia Elliott’s essays weave the personal with the political, drawing on her background and life experiences to explore a range of topics: colonialism, racism, mental health and depression, abuse, sexual assault, poverty and capitalism, and more. They’re elegantly written, constructed with a fine attention to style while remaining rooted in a profoundly honest, unalloyed anger.

When Indigenous writers are taken seriously, their work almost inevitably remains constrained within a narrow literary sphere delimited by what publishers think Indigenous writers can and should write about, and by the ways in which their identity is expected to drive their work. Elliott goes far beyond such boundaries. With its eloquent combination of love, anger, and impassioned insight, Elliott’s essays in A Mind Spread Out on the Ground are a must read. – Hans Rollmann

Read more about this book here on PopMatters.

Mr. Straight Arrow: The Career of John Hersey, Author of Hiroshima, by Jeremy Treglown [Farrar, Straus and Giroux]

John Hersey is best known for Hiroshima, his account of the atomic bombing of that city and its aftermath. His was one of the first widely published accounts of what happened there, and the book has been continuously in print since its initial publication in 1946. He covered Hiroshima and America’s race riots with empathy, courage, and profound humility.

He would reflect, in later years, on the ways in which this upbringing helped inculcate an early awareness of cultural relativism, of class difference and social injustice, of racism and the nefarious nature of colonialism and other forms of privilege. Jeremy Treglown’s biography, Mr. Straight Arrow, should bring a new generation of readers to Hersey’s work.

Read more about this book here on PopMatters.

Never Enough: The Neuroscience and Experience of Addiction, by Judith Grisel [Cambridge University Press]

Addiction is a beast and it is also one of the biggest health issues the world currently faces. Dr. Judith Grisel, a recovering addict and renowned behavioral neuroscientist, digs into the difficult and complex layers of how addiction works, how our minds react to addictive tendencies and substances, and how addiction can debilitate aspects of the body. The information that Grisel explains isn’t brand new, per se, but it is written with candor, wisdom, and insight that makes it compelling to hear and vital to address. She’s compassionate and caring (having experienced all manner of substance addiction herself), but she also drives home a deadly point that addicts and non-addicts alike need to hear: every drug’s effects wear thin and the toll on the brain mounts with each use.

Never Enough is terrifying, eye-opening, but also utterly readable. Her book made me rethink certain behaviors that I once considered harmless and benign. When a book can change your mind in a positive way, it should not be overlooked. – Scot Elingburg

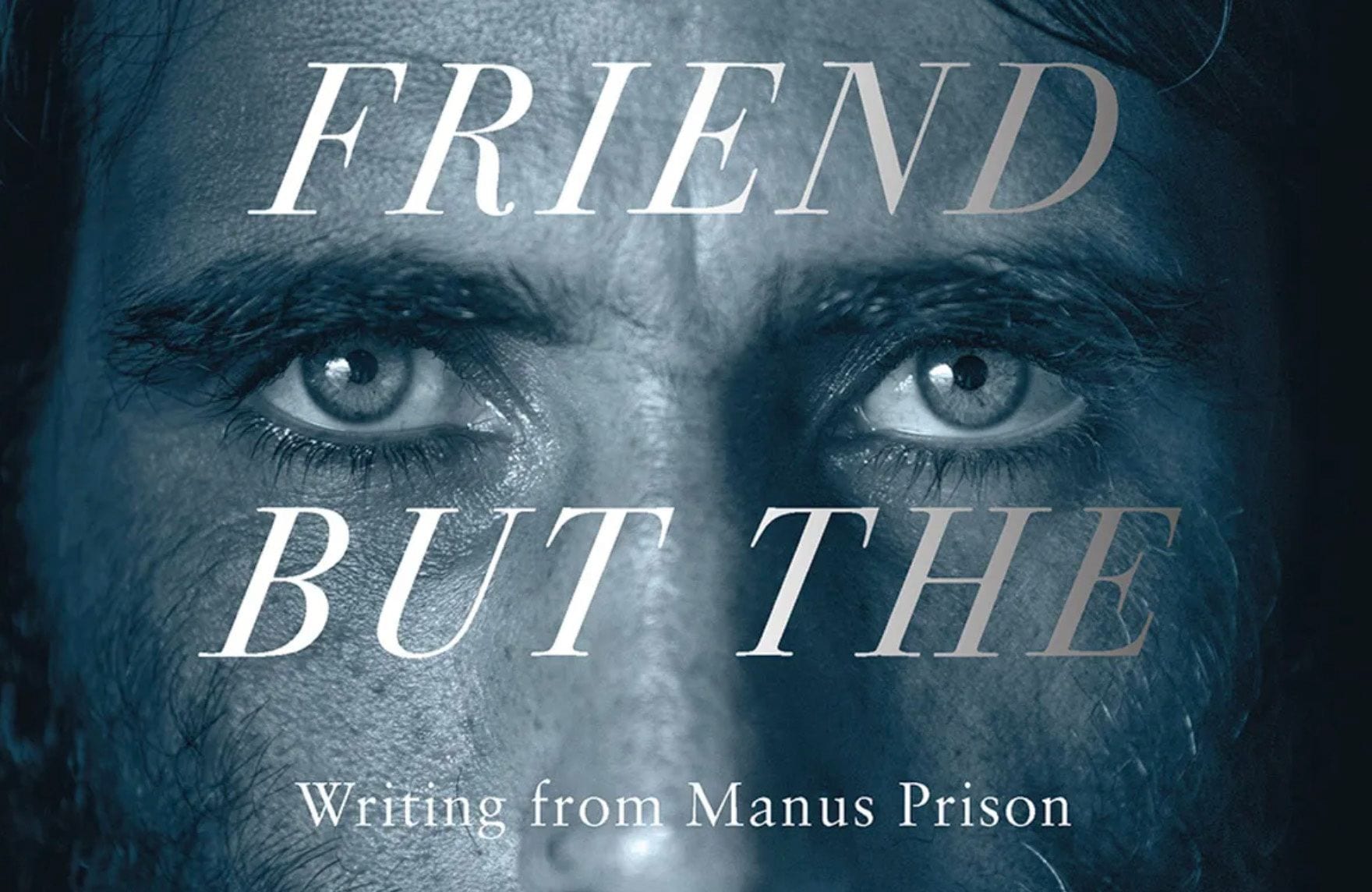

No Friend But the Mountains, by Behrouz Boochani [Pan MacMillan (AU)/ Anansi (CA) /Picador (US)]

When Behrouz Boochani won the Victorian Prize for Literature – Australia’s highest literary prize — it drew the attention of a much broader global audience to a writer who has been publishing gripping and powerful journalism and reportage, under the most trying of circumstances, for many years. His award-winning book, No Friend But the Mountains, is a poetic, autobiographical narrative which chronicles Boochani’s experience in the brutal and inhumane concentration camp system in which Australia imprisons asylum-seekers.

His intellectual and journalistic training, coupled with an eloquent capacity for literary expression, enables Boochani to bridge the lived experience of refugees with non-refugee audiences and to express it in the context of the critical social and political theory which shapes intellectual elites’ understanding of the refugee crisis. – Hans Rollmann

Read more about this book here on PopMatters.

Notebooks: 1936 – 1947, by Victor Serge [New York Review of Books Classics]

Victor Serge, a rare survivor of Stalin’s Terror, had a keen, razor-sharp intelligence and made observations that are highly relevant to our troubled times. As a teen, he grew up in an anarchist commune in the Belgian forests. As a young man in Paris, he aspired toward writing, but the anarchist gangs he hung out with were arrested for their robberies and he with them. Eventually freed, he travelled to Spain and witnessed its early revolutionary throes, before moving on to Russia where the Big One was already in progress. He rose through the Russian Revolution’s ranks and into the confidence of its leaders. When Stalin made his grab at power, our protagonist publicly and courageously opposed the tyrant, aligning himself with an anti-Stalin opposition that soon found itself imprisoned or dead. Our hero was the rare exception, granted a miraculous release from Stalin’s prisons, thanks to the work of his advocates abroad.

Serge puts on a wryly fatalistic attitude in the face of these threats and dangers in Notebooks: life continues, at least while it does. He offers sketches of many fascinating individuals as well: Trotsky; Andre Gide; Andre Breton; Anna Seghers; and dozens more. The book complements its hefty intellectual spaces with charming and quirky moments of life. – Hans Rollmann

Read more about this book here on PopMatters.

Occult Features of Anarchism, by Erica Lagalisse [New York Review of Books Classics]

Where does one draw the line between conspiracy theories, and politics-as-usual? The quick dismissal of conspiracy theories and conspiracy theorists, and their conflation in the Trump era with the image of racist poor white folk, reflects a certain classism on the part of intellectual elites, she warns. It’s not just a few marginal “rednecks” dabbling in conspiracies – any scan of social media shows they have far wider purchase. Conspiracy theories express an important dimension of popular culture, and they ought to be treated more seriously by scholars and activists alike. Even if they’re not active believers, millions of people are drawn to the conspiracy theorists of social media sites.

In in Occult Features of Anarchism, anthropologist Erica Lagalisse warns that we ignore conspiracy theory at our peril – Hans Rollmann

Read more about this book here on PopMatters.

The Old Is Dying and the New Cannot Be Born: From Progressive Neoliberalism to Trump and Beyond, by Nancy Fraser [Verso]

We’re facing a crisis, writes American critical theorist Nancy Fraser. Given the rise of neo-fascism and the economic plight resulting from skyrocketing income inequality, precarious jobs and sinking economies, many would probably agree with her. Many in recent years have blamed the crisis on neoliberalism – the economic deregulation inherent to that ideology, favouring privatization and an unregulated free market, has fueled inequality and poverty, which in turn has fueled the rise of fascism, xenophobia, militarism and other social woes.

But it’s not enough to blame neoliberalism, says Fraser in her latest work The Old Is Dying and the New Cannot Be Born. Neoliberalism is an economic-political system, not a worldview. Fraser’s prose is scholarly yet accessible, and her analysis is strikingly innovative. She is in many ways a Marx-for-our-times, and her work makes important and hopeful reading. – Hans Rollmann

Read more about this book here on PopMatters.

Open Season: Legalized Genocide of Colored People, by Ben Crump [Amistad]

Award-winning lawyer Ben Crump’s Open Season irrefutably documents how America’s treatment of Black Americans and other minorities is indistinguishable from genocide. Crump’s definition of ‘colored person’ encompasses queer and trans people who face murderous violence on a regular basis in the US; Muslims who are targeted for their faith; and women who are routinely sent to jail for decades for defending themselves against violent men.

Crump is deeply critical of American courts; given that many judges are appointed rather than elected, he observes, they actually have “the opportunity to focus on the high-minded ideals that America embodies. The judges can’t create legislation or overturn precedents arbitrarily, but they can be fearless in their interpretation of the Constitution.” Yet they are not. Instead, “the majority of the United States Supreme Court rulings over the years regarding race have been decided based on what is most detrimental to Black and brown people, not precedence.” Every American needs to read this book. – Hans Rollmann

Read more about this book here on PopMatters.

Ordinary Girls, by Jaquira Diaz [Algonquin Books]

Jaquira Diaz’s memoir, Ordinary Girls, provides an extraordinary guide to becoming fierce, strong, and loving in a world of monsters. It will be treasured and studied not just for its testimony of survival, but also its stunning and refreshingly consistent strength of style. Every page shimmers with assuredness and the strength of somebody who has survived to tell this story but also knows that survival is a daily process. Foremost to Diaz’s motivations seems to be her compulsion to express the survival instincts of an obsessed reader. Love the books that come into your radar, and they will love you back. – Christopher John Stephens

Read more about this book here on PopMatters.

Out of Our Minds: What We Think and How We Came to Think It, by Felipe Fernández-Armesto [University of California Press]

Against “the politics of the megaphone,” Fernández-Armesto surveys the fragile gap within which we live in his work, Out of Our Minds. He spans the whole recorded time of humanity and then some. He concludes that technology relied upon also delivers evil. People’s “moral incapacity to resist it” traps us in an ugly world. Sociobiology, postmodernism, and fundamentalism undermine our dignity and weaken our sanity.

Opposing a lemming-like rush to despair, this scholar wraps up this engaging study, rewarding close attention, by suggesting pluralism as paradoxically “the one doctrine that can unite us.” How long cherished diversity resists the imperious convergence of a monoculture remains to be seen, or feared. For conformity silences our imaginations. Our story makes a cautionary tale. – John L. Murphy

Read more about this book here on PopMatters.

The Peanuts Papers: Writers and Cartoonists on Charlie Brown, Snoopy & the Gang, and the Meaning of Life, Andrew Blauner, Ed. [Library of America]

Has any cultural institution had a bigger effect on American writers and artists than Peanuts? The answer is ‘no’, and if you disagree, The Peanuts Papers, collection of essays and observations makes the strongest case possible for Peanuts as a cultural behemoth. Writers and creators from Ira Glass to Ann Patchett line up to dissect and discuss every element of the Peanuts phenomenon. From cartoon histories to character studies, each entry is filled with heart and nostalgia and explains how and why a simple comic strip (a strip that creator Charles M. Schulz wanted to call “Li’l Folks”) helps us understand our fragile humanity. In these 33 essays, you’ll recognize how good a world with Peanuts really is.

Fair warning, you may want to keep a box of tissues close at hand. That’s how deep the world of Peanuts goes. – Scott Elingburg

Read more about this book here on PopMatters.

Pill, by Robert Bennett [Bloomsbury Academic]

The fact that many of us cannot get through our days without some sort of charmed talisman hanging around our necks or a magic medical suppository swimming through our bloodstreams is not always a subject for general or acceptable discussion. Legal mood regulators produced and promulgated by big pharmacology have made their definite mark over approximately the past quarter century as a means to control depression and maintain attention.

Robert Bennett provides a clear-headed and concise history of the introduction of mood stabilizers in American culture and the complications that have followed in this excellent installment of Bloomsbury’s Object Lessons, Pill. Pill succinctly and comprehensively charts the enigmatic relationship humanity has had with wonder drugs of all sorts, particularly here Thorazine through Adderall.

Read more about this book here on PopMatters.

Pious Fashion: How Muslim Women Dress, by Elizabeth Bucar [Harvard University Press]

Thanks to the ravages of our oversimplified and hateful political discourse in these times, the average American makes no meaningful distinction between Muslim nations at all. Turkey may as well be Iran. Iran may as well be Indonesia. And when we are asked to conjure up an image of a contemporary Muslim woman’s fashion in any of these three very different cultures, it’s hijabs, hijabs, hijabs across the board.

Because this type of gross homogenization of Islamic nations is inexcusable and because this type of glossing of the intersections of feminism, religion, and creativity is likewise inexcusable, we need to read Elizabeth Bucar’s Pious Fashion. Bucar is a professor of philosophy and religion, not a writer for a fashion magazine. Yet her style of reportage is blessedly clear and engaging, more in the manner of a sociologist or ethnographer than a pure theoretician.

You don’t even know what you don’t know about how Muslim women dress until you read Bucar’s Pious Fashion. – Megan Volpert

Read more about this book here on PopMatters.

Protest! A History of Social and Political Protest Graphics, by Liz McQuiston [Quarto Publishing / Princeton University Press]

Liz McQuiston’s Protest! encompasses an astounding breadth of emotion – from hilarious satire to utter horror. It highlights the timeless iconography of protest graphics, such as raised fists, skulls (and skeletons), mushroom clouds and missiles, and revels in the variety of its modus operandi: from posters and postcards to giant inflatables. But over and above all, this book pays tribute to the liberating concept of hard-won ‘freedom of speech’ throughout history, and which still has agency in current times.

The power struggles of the past, and their visual communication, have meaning for us now. Such resonances occur, again and again, throughout this entire collection. – Elisabeth Woronzoff

Read an excerpt of this book, courtesy of Quarto Publishing / Princeton University Press, here on PopMatters.

Revenge of the She-Punks: A Feminist Music History from Poly Styrene to Pussy Riot, by Vivien Goldman [University of Texas Press]

In her history of women in punk music, Revenge of the She-Punks, Vivien Goldman hefts the scene’s virtues and the vices into one heap and concludes that some of it was necessary, some of it was fun, and some of it was evil.

If you know nothing about women in music, punk is a perfect genre to start with because it really boils down the essential issues. If you know nothing about punk, Goldman offers just as solid a primer on the overall vibe as Legs McNeil and Gillian McCain’s Please Kill Me, plus a much more sweeping historical view than that touchstone ever did.

If you do know something about women in music, or punk music, or women in punk music, you’ll nevertheless find plenty of new ideas to dive deep on in Goldman’s seriously excellent treatise. Revenge of the She-Punks is not to be missed. I haven’t liked a feminist music book this much since Gillian G. Gaar’s, She’s a Rebel – Megan Volpert

Read more about this book here on PopMatters.

The Revolution That Wasn’t: How Digital Activism Favors Conservatives, by Jen Schradie [Harvard University Press]

Could it be that the internet and social media is innately in sync with conservative, right-wing ideology ScholarJen Schradie points out in The Revolution That Wasn’t that it’s not any one factor, but a confluence of factors, that make the internet more conducive to right-wing activism.

For activists on the left, digital activism is one among many organizing tools they use from time to time when opportunity, time and resources permit. Yet right-wing activists cleave to an almost religious drive to spread their word online, which accounts in part for their dominance in terms of online content production.

We must not delude ourselves into underestimating the scale of in-person and digital organizing that conservative groups are doing. Trump’s election, Schradie asserts, was not the result of bots or Russians or other bogeymen. It was the result of a highly organized and effective conservative movement. Only by understanding that will the left be able to come up with effective strategies to counter it. – Hans Rollmann

Read more about this book here on PopMatters.

The Sakura Obsession: The Incredible Story of the Plant Hunter Who Saved Japan’s Cherry Blossoms, by Naoko Abe [Alfred A. Knopf]

It doesn’t sound like quite as dramatic a story as the title makes it out to be, but in fact The Sakura Obsession is a beautiful and engaging narrative that’s surprisingly hard to put down. Author Naoko Abe – a journalist who did the English translation of the book herself – tells her story with a superbly compelling style, alternating between historical narrative and journalistic reportage.

She explores the philosophical shift in how cherry blossoms have been viewed over time, from their original role in symbolizing life and vigour, to their later symbolic role representing the ephemerality and fleetingness of life (used to such devastating effect in imperial and militaristic propagandizing). She explores the shifting role of the cherry tree alongside the political and cultural shifts that have marked modern Japanese history, including a rewarding look at their role in the Second World War, from Japanese colonialism in China to the training of kamikaze pilots.

Abe’s The Sakura Obsession chronicles the struggle to preserve diversity in a world of compulsive uniformity. There are some powerful metaphorical lessons in the histories presented here. – Hans Rollmann

Read more about this book here on PopMatters.

Say Nothing: A True Story of Murder and Memory in Northern Ireland, by Patrick Radden Keefe [Doubleday]

Say Nothing examines how and why Jean McConville, a widowed mother of ten, was abducted by those who included her West Belfast neighbors among masked vigilantes, in December 1972. Keefe credits 11 research assistants in his acknowledgments. His diligent mission was accomplished over seven trips to Ireland over four years and supported by documentation from a wide range of publications, oral and written archives, and attentive and thorough interviews.

One wonders if a researcher raised on the island could have brought the detached judgment needed to balance the intimate conversations and delicate details Keefe uncovers. Informers in the indigenous Irish culture, “touts”, have long been reviled and accusations of betrayal—merited or not—increased the death toll as McConville and others, at least some of them innocent, have been condemned. This narrative integrates dozens of people involved in “the Troubles”, and their testimony deepens the accuracy and poignancy of their recollections. – John L. Murphy

Showtime at the Apollo: The Epic Tale of Harlem’s Legendary Theater, by Ted Fox and James Otis [Abrams Books]

How do we measure the status of a performer’s Holy Grail like the Apollo Theater in 2019? Ted Fox and James Otis Smith’s beautifully realized, updated graphic history, Showtime at the Apollo, brings this rich history to life. Since 1934, from deep within the Harlem Renaissance through to the present time, the Apollo has stood to represent and speak for the heart and soul of a national sound. Who were we? How did we get here? Can a legendary venue like the Apollo really prove worthy of its reputation?

James Otis Smith’s illustrations make for a rich, beautiful, ideal accompaniment to Fox’s narrative. This graphic version of the history of the Apollo Theater is a beautiful, heartfelt, and rich tribute to a musical form, a vital location, and a pure American vision of connecting with the audience in the theater and everywhere else. We can feel the Apollo’s heartbeat on every page – Christopher John Stephens

Read more about this book here on PopMatters.

The Socialist Manifesto, by Bhaskar Sunkara [Basic Books]

While some might gaze with despair upon the fragmentation of today’s left-wing thought, others might see within that diversity the makings of the ‘environment’ of which Victor Serge writes. The proliferation of socialist and hard left cultural production — Sunkara’s Jacobin Magazine, radical publishing houses like Verso Books and AK Press in the UK, PM Press and Haymarket Books in the US, Black Rose Books and Fernwood Publishers in Canada, among others — are building the sort of critical mass of thought and literature which is a necessary base for such an environment.

Class is a more potent division now than at any point in the past century, and the dubious accomplishment of identity-based movements which failed to critique capitalism has been to replicate its injustices. Creating space for women, queers, black Americans and other minorities to enter society’s elites has done little to mitigate the broader problems of sexism, homophobia, racism, and other forms of oppression. Identity-based oppression and exploitation is woven into the fabric of capitalism, argue socialists. A better formula, assert Bhaskar Sunkara and other socialists, is to merge the struggles against capitalism and against discrimination. Socialists need to do better in fighting against identity-based discrimination, but that struggle will only be effective if waged as part of a larger struggle against neoliberal capitalism.

It’s not exactly a manifesto, but The Socialist Manifesto is important reading for our tumultuous and transformative present. – Hans Rollmann

Read more about this book here on PopMatters.

Some of Us Are Very Hungry Now, by Andre Perry [Two Dollar Radio]

Andre Perry’s beautiful, brilliant, bold debut collection of essays, Some of Us Are Very Hungry Now, doesn’t fall into the minutiae of solipsistic reflection that riddles many debut collections. Here, Perry takes his place with such strong works as Paul Crenshaw’s This One Will Hurt You and Randon Billing Noble’s Be with Me Always.

The collection is tantamount to a slice from the Americana songbook. These essays are ballads, images from the self, isolated and marginalized in other countries and in his own land. These are songs of identity and sexuality and expectations the world has of African American males. If the goal of a literary traveler is to show how connected we are to one another, this book is an assured indication of deeper glories yet to come. – Christopher John Stephens

Read more about this book here on PopMatters.

Ten Innings at Wrigley: The Wildest Ballgame Ever, with Baseball on the Brink, by Kevin Cook [Henry Holt and Co.]

If you’re a baseball fan, it’s a great time to be alive. It’s also a great time to be an avid reader. Baseball is an American institution but it’s been dragged through the mud for decades and, in the process, it has lost some of its heart and soul since. Luckily, Kevin Cook doesn’t bother digging up long-buried dirt in his book, Ten Innings at Wrigley. Instead he focuses on tiny details in player’s careers and lives that made the 1979 game at Wrigley Field, a game between the hometown Chicago Cubs and their East Coast rivals the Philadelphia Phillies, such a slugfest.

The game exploded in the first inning with winds coming through the stadium keeping baseballs in the air and the runs on the board. Players like Mike Schmidt, Bill Buckner, Tug McGraw, and Pete Rose were on the field that day and they most remember that day in stark and vivid detail. Cook writes with a fan’s heart and a journalist’s eye about that memorable day but, more importantly, he plays up the inherent hope and optimism that baseball has. – Scott Elingburt

Theory, by Jordan Alexander Stein [New York University Press]

Graduate school, everyone? The glory of Jordan Alexander Stein’s Theory is that it unmasks both the utility and the futility of theory. Theory: as a thing that the academy engaged in especially from the mid-’90s to the mid-00s, for all of us who went to graduate school during that time period, almost regardless of particular academic discipline, our encounters with theory turn out to be weirdly similar.

This is due to the ways academics use theory and the feelings produced by that experience. Stein neatly divides these feelings into five chapters: silly, stupid, sexy, seething, and stuck (and bonus points for keeping to words that begin with S, because of both the arbitrariness and delightful superfluity of it). Each of the chapters examines a feeling by attaching it to a different facet of postmodernism that highlights a certain theorist.

The chapter on silliness hinges on Adorno with occasional dips into Derrida. Stein considers how the end of the ’90s promoted a serious investment in irony; that is, we were quite serious about using these ideas to crack jokes. Pink Freud anyone? Chaka Lacan? See also: Hedwig’s dissertation, You, Kant, Always Get What You Want. Kant is the focus on the chapter on stupidity. Because his theory is bad. And badly written—and very badly deployed by graduate students everywhere. Guess who is the dominant feature in the chapter on feeling sexy? Theory is for diehards. And die hard we do, don’t we? – Megan Volpert

Read more about this book here on PopMatters.

A Theory of Jerks and Other Philosophical Misadventures, by Eric Schwitzgebel [MIT Press]

Though a professor at UC-Riverside who may do a fair impersonation of the tweedy and tenured, Eric Schwitzgebel has long been garnering a reputation as a highly accessible explainer, primarily through his excellent blog, The Splintered Mind. Each of the five sections here has a different and very loose subject heading. Section One, “Jerks and Excuses”, focuses on ethics. Other questions the author weighs in on: How much should you care about what you feel in your dreams? Is it perfectly fine to aim for moral mediocrity? Do our intentions matter if the outcome of our action is terrible? What does it really mean to do the most you can do?

Schwitzgebel’s excellent and accessible philosophy in A Theory of Jerks and Other Philosophical Misadventures would be great at parties—just open up to any random three-page essay, read it aloud, and let the conversation flow. – MEgan Volpert

Read more about this book here on PopMatters.

They Called Us Enemy, by George Takei [Top Shelf Productions]

In graphic memoir They Called Us Enemy, iconic Star Trek star George Takei draws from his family’s experience of Japanese-American internment camps to warn of a potentially dark future. The iconic Takei, whose progressive wit has in recent years taken social media by storm, was spurred, in part, to produce the graphic memoir by his observation of history repeating itself. Contemporary concentration camps are heinously immoral as a matter of general principle, and there’s terrible irony in using former Japanese-American internment camps like Oklahoma’s Fort Still to imprison America’s desperate immigrants.

Takei has worked assiduously over the years to fight racism (and other forms of discrimination) and to honour the culture and historical legacy of Asian-Americans. His life and career offers a poignant example of a principled man who is both proud of his country’s accomplishments yet refuses to ignore its many continued shortcomings. There is a tone of profound concern in the contemporary commentary which bookends this tale, that an America which for many years had been slowly working to improve itself may now be floundering and sliding backwards. If America fails to remember and learn from its historical mistakes, suggests this narrative, its future may be in jeopardy indeed. – Hans Rollmann

Read more about this book here on PopMatters.

This Land Is Our Land: An Immigrant’s Manifesto, by Suketu Mehta [Farrar, Straus and Giroux]

Suketu Mehta’s This Land Is Our Land is a book truly worthy of its sub-title. A stirring manifesto for immigrant rights, it’s also much more. It’s an invaluable reference aid, compiling rich data and statistics on every angle of the refugee crisis – from the crime rates of undocumented migrants (less prone to crime than American-born citizens) to the dollar value of their contribution to the economy (trillions of dollars in the US alone). What’s the price-tag of reparations? What’s the cost of colonialism?

But it’s more than simply another report on the refugee crisis. This Land Is Our Land is an unapologetic, angry manifesto supporting the rights of migrants to move. The fiscal benefits of immigration – which are enormous – are a boon to the economies of nations that accept them. Immigrants and refugees have a fundamental right to move to the rich countries of the western world, and Mehta articulates in persuasive, elegant prose the arguments in favour of this right – from the violent war and climate change crises directly caused by western nations, to the lingering impacts of colonialism.

Mehta’s work is among the most comprehensive, clearest, lucid and persuasive arguments in favour of immigrant rights yet written. It’s vital reading for anyone looking for arguments and data to unmuddy the rhetorics of white panic, and indeed vital reading or anyone who cares about the future of our world. – Hans Rollmann

Read more about this book here on PopMatters.

This One Will Hurt You, by Paul Crenshaw [Mad Creek Books / Ohio State University Press]

Paul Crenshaw’s This One Will Hurt You is a beautiful meditation on life in rural America. It’s about understanding and accepting painful memories, about drawing from the dark times not to exploit them so much as to fully accept that such things happened and we passed through them and came out OK.

All 18 of the essays in this volume weave themselves into a world where the sadness of repressed family anger is forgiven through the grace of a beautiful essay. But they’re not all easy — none of them are bland and comfortable and non-threatening. “We are shameful creatures scared of death,” he writes near the end of the title essay.

Each entry in this book delivers on the promise of its title. This one will hurt, the next one will support, and yet another will challenge. No matter which drink you choose from this case, you’ll be surprised by its staying power. – Christopher John Stephens

Read more about this book here on PopMatters.

This Searing Light, the Sun and Everything Else: Joy Division: The Oral History, by Jon Savage [Faber & Faber]

Author Jon Savage, the compiler and editor of all the interviews in This Searing Light, the Sun and Everything Else, was a source close to the Joy Division as well as the Factory Records team that helped launch a musical movement in Manchester. Given all of the front line accounts during this furtive punk moment in the late ’70s, it appears that Savage was able to come away with some new angles to the old story — Ian Curtis’s personal dilemmas in addition to his epilepsy, the severity of said epilepsy, the band’s inability to understand it all, the manager and the label boss’s failure to act properly, and the multitudes that witnessed it first hand and have never forgotten the impact it left on them.

As much as the story of this band has been pillaged, This Searing Light proves that there were still more Joy Division stories to be told. There’s room in the Joy Division universe for this book. As far as I’m concerned, it’s perfectly okay if there’s now nothing left to tell. – John Garratt

Read more about this book here on PopMatters.

William Stoner and the Battle for the Inner Life, by Steve Almond [IG Publishing]

IG Publishing’s Bookmark series provides a platform for very strong voices with moderate name recognition to write about the books that have inspired them deeply. This series is for feeling-fueled rants, not stuffy block-quote-laden analyses. We don’t need to have read John Williams’ 1965 book, Stoner, to enjoy Steve Almond’s love of the book; we just need to see the play by play application of the lessons that emerged from Stoner as they occur to Almond during a lifetime of rereading this book. He first gets his hands on it in graduate school, and it deeply imprints his evolution as an academic, in addition to later making him a more reflective husband, father, teacher, and citizen.

Almond zooms in on the way Stoner articulates the battles of every inner life, including ours and Almond’s and Williams’. These battles have an innate timelessness in their motifs that Almond then artfully tracks through the shifting contexts of his apprehension of its lessons. He pokes at old wounds, opening them again and again in homage to and in service of the legacy of the unrelieved narrative technique that Stoner impressed him so mightily in the first place.

If you’ve ever read Williams’ Stoner, you have no doubt of the need of Almond’s moving tribute to it. If you have not read Stoner, Almond’s William Stoner and the Battle for the Inner Life will convince you that you should. – Megan Volpert

Read more about this book here on PopMatters.

This Woman’s Work, by Julie Delporte [Drawn & Quarterly]

Julie Delporte’s graphic memoir, This Woman’s Work, documents her private and professional search for her place in the male-dominated field and world of graphic fiction and comics. Indeed, Delporte is a female artist documenting her private and professional search, which is life-long and takes her on a non-linear path around Europe and North America and deep into her own past.

She fills her the book with personal reproductions of works by female artists, each linked to critical moments in her own life. When she imagines having to raise a child on her own, she sketches a Mary Cassatt painting of a mother holding a child, giving the image a double meaning, since it both represents her possible self and the artistic lineage she is constructing.

A central trauma permeates but does not define Delporte’s work. The memoir is much more of an attempt to construct something new, even if it is necessarily incomplete and tentative as she wanders between continents and decades of memories. – Chris Gavaler

Read more about this book here on PopMatters.

The View From Somewhere: Undoing the Myth of Journalistic Objectivity, by Lewis Raven Wallace [University of Chicago Press]

Lewis Raven Wallace’s The View from Somewhere is an exceptional study in the history and development of the concept of journalistic objectivity – and all the problems associated with it. ‘Objectivity’ stands uneasily on a shaky throne. Never fully accepted by journalists – especially those who do not identify with the white, cis-men elites who defined that orthodoxy – objectivity come under increasing attack in recent years. Notions of ‘objectivity’ and ‘balance’ are wielded in ever more brazen and manipulative ways by an ever more aggressive right-wing in the United States and elsewhere.

The View from Somewhere is an outstanding and urgently needed critique of journalistic orthodoxy. It questions who is served best by claims of ‘objectivity’ and ‘balance’ and exposes the hidden biases they disguise. Offering some new directions for journalism, it also offers important food for thought for anyone who aspires to practice the trade, and ought to be required reading in journalism schools everywhere. – Hans Rollmann

Read more about this book here on PopMatters.

What Time Is It? by John Berger and Selçuk Demirel [Notting Hill Editions / New York Review of Books]

Shortly before he died, John Berger, the famed painter and intellectual chose to use his time in one last artistic collaboration—about time. He was very fond of collaborations, having worked on dozens of book projects with family members, artists, and other writers over the course of more than five decades. The last project was his third book in cooperation with Turkish illustrator Selçuk Demirel. In 2012, they published Cataract, with Demirel providing the drawings that would help illuminate Berger’s thoughts on the increasing loss of his eyesight. Their second book, Smoke, is a paean to the cigarette and forthright engagement with the thing we hypocritically prefer to banish from public life even as factories continue to pollute the air. Indeed, these two will gleefully pet a paradox when they find one.

Beginning from the notion that time is precious, the What Time Is It? works through the narrative or historical value of time, then on to the commonplace that time is money and often has a steep exchange value. Finally, time morphs into the surreal dreamscapes of creativity as Berger reckons with his own death and legacy.

Although the topics in John Berger and Selçuk Demirel’s excellent What Time Is It may instinctively feel morbid and fraught, the overall effect is quite satisfying, even tranquilizing. – Megan Volpert

Read more about this book here on PopMatters.

Year of the Monkey, by Patti Smith [Alfred A. Knopf]

What does Patti Smith care if the corporate publicity machines don’t grease any wheels in her name? She has no shortage of loyal readers and listeners. Those who still want to find her can do so with ease. She doesn’t seem to need the money. She’s got a punk mentality about it all; she’d rather just keep her head down and write some more—which brings us to Year of the Monkey.

On the one hand, it would be easy to judge that this book strongly resembles everything else she’s written. It’s a memoir covering the year of 2016: Smith was heading into her 70th birthday in a county heading toward electing Trump. Year of the Monkey covers Smith’s traveling to a variety of places, where she stayed and what she ate. But nobody thinks she’s phoning it in, here. Year of the Monkey is as genuine a collection of Smith’s life force as each of her preceding books. It is satisfying to catchup with her each time, seeing what new things she’s thinking about in her same beautiful way. – Megan Volpert

Read more about this book here on PopMatters.

Honorable Mentions

Editor’s note: Articles on the following books were received and published after this feature, “PopMatters‘ The Best Books of 2019: Non-Fiction” published. We thought we would add them here, anyway, to showcase additional books released in 2019 that we really enjoyed and recommend to you.

Fandom as Methodology: A Sourcebook for Artists and Writers, eds. Catherine Grant and Kate Random Love [Goldsmiths / MIT Press]

Over and over again in this anthology, the collapse of the distinction between a fan and an academic proves queer (as in gay, certainly, but also as in strange). The dozen features in the 32-page section of “Artist Pages” are beautifully strange, depending on how much the reader might know about the source material. It would be a snap to design a super engaging graduate-level course around this anthology in a variety of Humanities disciplines, especially if you’re already interested in Sedgwick, Barthes, or Derrida. Fandom gives life.

I am officially a huge fan of Fandom as Methodology because the articulation of these concepts ultimately leads to our liberation from the tyrannies of paranoid strong theory in favor of play and experiment, from the presumption of distanced academic writing in favor of up close and personal loving of one’s subject. – Megan Volpert

Read more about this book here on PopMatters.

I Used to Be Charming, by Eve Babitz [New York Review of Books]

There’s a particular kind of young woman in the late 1970s that Eve Babitz represents in her writing: sexually free but not necessarily available, well read and well educated but not publicly bookish, fashionable without really ever worrying about whether her outfit works. This is, at least, the public persona she channels in her essays.

Babitz is more than a child of the ’60s. She is also ’50s glamour and ’70s glam, reflecting on the decades with her sharp eye on cultural trends and transformations. A writer’s legacy, for good or bad, is that what they have written holds a particular moment in time. In this way, Eve Babitz is always charming. This collection does not preserve her work as a thing of the past but rather invites her influence to contemporary readers and writers alike. – Linda Levitt

Read more about this book here on PopMatters.

James Baldwin: Living in Fire, by Bill V. Mullen [Pluto Press]

That James Baldwin’s relationship with his home country was fraught for the bulk of his relatively brief life is an understatement. Living as a closeted black homosexual man in a country that would not pass a major Civil Rights Bill until the mid-’60s and not acknowledge the possibility of non-binary gender identification until much later, Baldwin emigrated to Paris in 1948, at the age of 24. He spent most of his life commenting on his country from afar, working and reporting on major US Civil Rights events and figures. His works about race, class, politics, and sexuality were always fearless, never quiet, and surrendered nothing. – Christopher John Stephens

Bill Mullen’s James Baldwin: Living in Fire is an important addition to this ongoing assessment and examination of a writer whose legacy was strong during his lifetime and remains vital to this day.

Read more about this book here on PopMatters.

New Kings of the World: Dispatches From Bollywood, Dizi, and K-Pop, by Fatima Bhutto [Columbia Global Reports]

Read more about this book here on PopMatters.

Enjoy Fatima Bhutto’s interview with John A. Riley here on PopMatters.

Switched on Pop: How Popular Music Works, and Why it Matters, by Nate Sloan and Charlie Harding [Oxford University Press]

With their new book, Switched on Pop: How Popular Music Works, and Why it Matters, launched from their Switched on Pop podcast, Nate Sloan and Charlie Harding have leaned into their scholarly tendencies. The book is designed to further formalize, even make academic, the case made by the podcast: pop music is musicologically complex. It’s written in a collegial “we” à la Deleuze and Guattari, it has footnotes and references to cultural theorists, and it has institutional bona fides, having been published in a beautiful hardback edition by the prestigious Oxford University Press. But for all of that, the physical object of the book itself is playful: it looks and feels like a tiny textbook, with a simple, primary-colored cover and whimsical diagrams peppered throughout.

Switched on Pop is an important text in the growing cosmos of pop-culture-oriented criticism.The short essays are a fitting companion to the podcast, and taken together, the two outlets of the Switched on Pop project promise an exciting future for music criticism in the new media sphere. – Max McKenna

Read more about this book here on PopMatters.

We Have Always Been Here: A Queer Muslim Memoir, by Samra Habib [Viking]

We Have Always Been Here is a work of tremendous beauty and wisdom. Samra Habib’s memoir could easily have been bitter, harsh, righteously angry. But it’s not. It’s angry, resolute, and impassioned when it needs to be, but Habib complements the bitter memories with the beautiful ones.

There is a sensuous aesthetic to it, expressed in layers of taste, smells, and sights that evoke familiarity amid the turmoil and change. From waking up “to the warm and peppery smell of pakoras frying in the kitchen” to childhood motorcycle trips around Lahore with her father, “whiffing the aromas of cardamom, turmeric, simmering meat, and bubbling naan,” the narrative is an epicurean and sensory delight. Even in Canada, she finds solace in the beauty.

Matter of fact in its presentation of difficult material — sexism, child marriage, emotional and sexual abuse — what’s most striking about Samra Habib’s memoir, We Have Always Been Here, is the sense of compassion with which she writes. – Hans Rollmann

Read more about this book here on PopMatters.

At PopMatters we tend to be drawn toward cultures’ tributaries instead of the crowded, rushing mainstreams. It’s in these places, where things are rougher, that we find trained historians rubbing shoulders with smart outsiders, where artists dare us to follow them and intellectuals show us where and who we are and from whence we came with discomfiting yet engaging clarity. There is no certainty in these places — but there are many possibilities.

Notably, of our many books listed here, graphic works straddle the Non-Fiction and Fiction favorites. Perhaps for non-fiction that means that sometimes the best way to show the truth is to draw a picture.

Other works come in the forms of biography, memoir, history, essay collections, political and cultural criticism, art, travel literature and more. What follows is a list of our favorite non-fiction titles, in alphabetical order by title, that we’ve sought out, or been drawn to, in this terrible and tumultuous year.

We think you’re going to find much to enjoy and learn from, here. Engage with these books and they will change you. That’s why you’re here, isn’t it?

- Life Isn't Binary and Neither Is the Coronavirus Pandemic - PopMatters

- Nicholas Buccola's The Fire Is Upon Us Is Lost in the Smoke - PopMatters

- Nicholas Buccola's 'The Fire Is Upon Us' Is Obscured by the Smoke - PopMatters

- The Best Books of 2020: Non-Fiction - PopMatters

- The Best Books of 2020: Fiction - PopMatters

- Interview: Gabriel Bump - PopMatters

![Call for Papers: All Things Reconsidered [MUSIC] May-August 2024](https://www.popmatters.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/all-things-reconsidered-call-music-may-2024-720x380.jpg)