Eddie Cochran, by all accounts, didn’t want to go to England. A little more than a year before his trip in the spring of 1960, he’d lost Richie Valens and Buddy Holly, friends both, in what still might be the most famous plane crash in rock ‘n’ roll history. Cochran became morbid, or so the story goes. Either way, he wanted to stop touring and concentrate on studio work in L.A. But there were obligations to meet, including a string of shows in Great Britain.

It was essentially the contradiction in the story told in Cochran’s biggest hit, “Summertime Blues”: you gotta work so you can do what you want to do, but you can spend so much time working that you never find your freedom. You’re caught.

On April 16, 1960, Cochran and his fiancée, the songwriter Sharon Sheeley, along with his tour manager and Gene Vincent, had just left the final concert in Bristol and were taking a cab to the London airport. A tire blew out. Cochran was thrown from the car, and he died the next day.

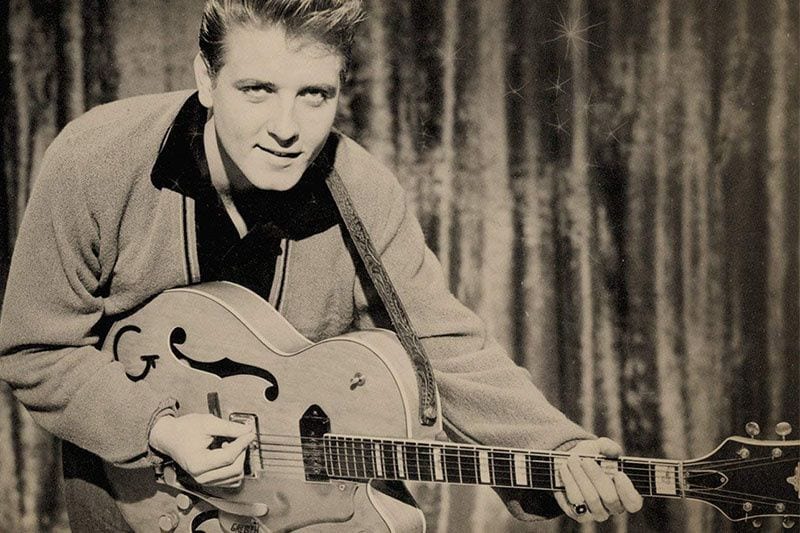

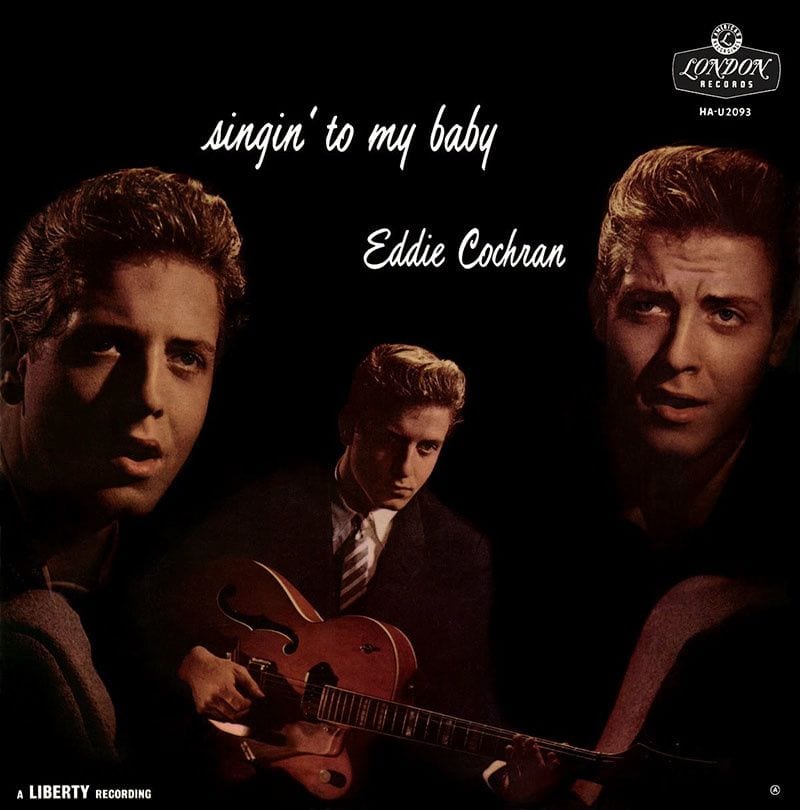

As a cultural figure, Cochran is made of shadows and light. He was the good kid with a dark streak, handsome and wholesome but capable of a rebel’s glare. His voice ranged from a screeching rockabilly tenor to a doo-wop bass. The studio tried to fix him with schlocky crooner pop on his only full-length, Singin’ to My Baby (Liberty Records, 1957), a clear reaction to and capitalization on the Elvis Presley phenomenon. But those songs are just historical information today while “Summertime Blues”, “Somethin’ Else”, “C’mon Everybody”, “Cut Across Shorty”, “Jeannie Jeannie Jeannie” and other singles are still alive, bristling with his alley-cat voice and frenetic rhythms. If he has endured as a romanticized Fifties icon, the best of his performances are exceptional not for their musical innovation or the profundity of what’s said, but for an electric energy that seems to be fighting its way out of the deadness of contemporary life.

“Summertime Blues” is Cochran’s greatest performance and, maybe, rock ‘n’ roll’s purest expression of the contradictions faced by the working class. Released in 1958 and co-written by Cochran and his manager, Jerry Capehart, the song tells the story of a teenage kid who’s discovered that if he’s going to have any fun over the summer, he’s going to have to work, but if he works all summer, he won’t have any time for fun. The kid tries to call his girlfriend for a date, but the boss says he’s gotta work late. His parents won’t give him the car unless he works; he calls off sick from work (presumably he is sick), and as such… no car. No car, no date.

Near the end of the song, Cochran and Capehart pull a Chuck Berry move: the kid’s gonna take his case to Congress. Berry was keenly aware of the injustices of the US legal system, of course, and for that reason among others his songs always breathed in and out the expanse and meaning of the United States as a nation. Right or wrong, whenever I hear this verse it seems like the kind of thing Berry would have written. Anyway, Cochran’s hero blows his two weeks’ vacation by heading first to the United Nations, which seems a little misguided. (That the kid has two weeks for vacation is the song’s only suggestion that the protagonist has a full-time job, not a summer job, and that he’s maybe a high-school dropout, like Cochran himself. More on that in a moment.) Then the kid climbs the steps of the Capitol building and finds his congressman, only to be told what teenagers today are told: “I’d like to help you, son, but you’re too young to vote.” In other words, What can you do for me? Nothing? Get out of my office.

Yes, it’s all the stuff upon which ’50s-era nostalgia is built, especially youth culture and conservative gender norms. (What, Suzy, or Mary, or Jeannie don’t have cars? Or would our hero not want them to drive him around or pay for the date?) The kid ruining his own vacation by taking his case to Washington D.C. is tongue-in-cheek humor, and I don’t know, but maybe there were some parents in 1958 who thought, “See? He doesn’t know what to do with the freedom even when he’s got it!”

But “Summertime Blues” doesn’tstick around because it’s about being a teenager. The song sticks around because it expresses the trap of the hourly-wage life, the dilemma of working for your living, and working hard, working long hours at menial tasks, only to come home and collapse on the couch. This is living? This is the American Dream?

You don’t need to be a teenager to understand that. As a matter of fact, I would bet that the allure of the song depends on how its expression of economic frustration, frustration about time and energy and purpose, carries over into one’s adult life. Cochran was 19 when he recorded the song, and in 1958 the voting age was 21. The line about having two weeks’ vacation is one of the song’s most precise details, suggesting that the singer works full time but hasn’t been at it very long. So there’s some independence… but not much. Especially if, post-Great Recession, you had to move back home. Especially if you’re 50 and got laid off and now you need to ask your wife or husband for the keys to the only car. Especially if you work a job under a demanding boss, or if that boss is you.

“Summertime Blues” is a working class song more than it is a song about the ’50s or a song about being a teenager or even what the publishing industry calls a “new adult”, i.e., 18-24-years-old and presumably possessing some cash to burn. It’s a song about work becoming your biggest responsibility, an overwhelming dictator in your own life, until you hardly have a life anymore. It’s a funny song, but in a laughing-to-keep-from-crying way. After all, it’s a blues. The contradiction is in the title, and in the chorus:

Sometimes I wonder what I’m a-gonna do

But there ain’t no cure for the summertime blues

The song takes itself seriously no matter how ludicrous its final verse may seem. “There had been a lot of songs about summer,” Capehart said of the song, “but none about the hardships of summer.” You won’t hear that in the lyrics so much as in Cochran’s pinched voice, the raspy desperation and yearning.

It’s not a coincidence that the best covers of “Summertime Blues” emerged from working-class genres like rock and metal. In the proto-metal group Blue Cheer’s 1968 cover of the song on their album, Vincebus Eruptum, the guitars are all fuzzed out, the rhythm turned to lead, but most importantly, Cochran’s bass-voiced “adult responses” — “My boss says, ‘No dice, son, you gotta work late”—are replaced by short instrumental solos. (I wish I could say the bass solo rocks. Sorry.) Blue Cheer throws in a little of Hendrix’s “Foxy Lady” for good measure.

This is the arrangement the Who plundered, first in the studio during the sessions for The Who Sell Out, and then for their live set as captured on Live at Leeds, though they give the key chord riff into a very Who-like syncopated rhythm. Wisely they reinserted the adult responses, especially since in the late ’60s it seemed even more criminal that an eighteen year-old couldn’t vote but could be sent to Vietnam.

You can follow this arrangement all the way from Flaming Lips’ 1986 punk version on Here It Is, which gives you an idea how Nirvana would have covered it, into the new millennium with Rush’s version on Feedback (2004) and, recently, a strong cover by the American noise rock band ’68 on their 2017 album Two Parts Viper. The latter two cut the adult responses again, but ’68’s version includes the final put-down by the Congressman character. Their version takes the song back into the real fusion of abandon and frustration at the heart of Cochran’s recording, melding psychedelic breakdowns with hardcore riffs.

Then there’s Bruce Springsteen’s take on the song during his 1978 Darkness on the Edge of Town tour. In August at the Agora in Cleveland, local deejay Kid Leo introduces Springsteen by saying, “Ladies and gentleman: the main event. Round for round, pound for pound, there ain’t no finer band around!” Springsteen, sounding like quite the New Jersey greaser: “He musta memorized that at home.” His version with the E Street Band is probably the most faithful to Cochran’s, with saxophonist Clarence Clemons supplying the “adult” voice, but its also a master class in the E Street “best bar band in America” sound. It isn’t nearly as stunning as some other ’50s-’60s covers Springsteen has pulled off, but when the band holds the last chord, drops it down once, then one more into a minor chord before launching into “Badlands”, “Summertime Blues” takes on a new context within Springsteen’s own work. Suddenly he’s quite obviously the child of Eddie Cochran and Chuck Berry.

Sandwiched into all of this must be T. Rex’s 1970 cover, included as the B-side of their first hit single “Ride a White Swan”. This has to be the oddest and most sensual version of “Summertime Blues”, with Marc Bolan’s soft-spoken, shaky, almost alien vocals contesting the testosterone in most other versions (James Taylor notwithstanding). Driven by an annoying bongo and a relentless acoustic guitar that sounds like its strings haven’t been changed in a couple years, this “Summertime Blues” is for all the introverts, and thank God, because nerds get left out of the working class all the time.

Maybe it’s just Bolan’s voice, but T. Rex’s “Summertime Blues” gets at the alienation between a worker, their work, and what their work produces that is at the heart of Marxist theory and, yes, Cochran’s original performance. It’s the long story of people trying to determine the outcome of their own lives, the simple idea of sovereignty over one’s own body and what one does productively with it: control, self-production of material and identity, ownership. And when this story, this need for and right to self-determination, finds itself thwarted despite playing by the rules of work and the regulations of capitalism—when the whole damn thing gets called into question, as it does, fundamentally, in “Summertime Blues”—then we may have arrived at a fruitful way to think about working class music itself.

The only cure for the blues is the song itself: its performance and hearing it. “Summertime Blues” liberates, like blues songs do, but only temporarily. It’s a way to cope with the disease of capitalism, and sometimes that’s what you need. Better that than nothing.

For this reason, “Summertime Blues” seems particularly apt in this summer of 2018, this summer of America’s president cavorting with the authoritarian leaders of North Korea and Russia, a summer when any pretense that corporate earnings don’t control America’s democracy has been dropped—and yet, a summer that seems very much like the summer before it, and the summer before that. There’s a sense of intractability. The feeling that the struggle to get by makes it impossible to have the energy or the time to storm the barricades. That’s what American capitalism has achieved in 2018: maximum depression.

As rebellions go, “Summertime Blues” ain’t much, perhaps.

That said, the only hope is for ordinary people to produce the meaning of their own lives, and this will start with what it’s always started with: questioning the ordinary shit we endure. When that happens, suddenly you can understand “Summertime Blues” for what it really is.

A protest song.

![Call for Papers: All Things Reconsidered [MUSIC] May-August 2024](https://www.popmatters.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/all-things-reconsidered-call-music-may-2024-720x380.jpg)