In the late ’60s and early ’70s, popular music sought to break new ground as often as possible. Along with the reinvention of established artists came the emergence of an entirely new genre — progressive rock. Often categorized by its lengthy durations, incredible musicianship, and eccentric timbres, as well as the inclusion of of odd time signatures, bizarre narratives, and wildly imaginative artwork, the genre gave birth to some of the most unique bands of all time, including Yes, King Crimson, Genesis, Gentle Giant, Pink Floyd, and ELP. However, perhaps no group at the time (or since, for that matter) had a more brilliant, unique, and charming mixture of catchy songwriting, complex instrumentation, poignant lyricism, idiosyncratic vocals, and sonic evolution than progressive folk pioneer, Jethro Tull.

Lead by flutist/singer/songwriter/guitarist Ian Anderson (whose earthly yet embittered voice and live theatrics were a crucial part of their persona) and made even more distinctive by the impeccable techniques of guitarist Martin Barre, Jethro Tull has always been respected for its potency and purpose. Sadly, like with most artists, many people only regard the band for a handful of their songs, such as “Aqualung”, “Locomotive Breath”, and “Bungle in the Jungle”. While these tracks are certainly worthwhile, only true fans and genre aficionados grant the group proper revere for pushing boundaries and challenging conventions as thoroughly and consistently as it did.

Case in point — their 1972 masterpiece, Thick As a Brick. Groundbreaking in its form, length, packaging, lyrics, and concept (more on that in a bit), the record saw Anderson’s most extravagant vision (up to that point) brought to colorful life with the help of his troupe (which, aside from Barre, included pianist John Evan, bassist Jeffrey Hammond-Hammond, percussionist Barriemore Barlow, and string arranger David Palmer). Full of catchy melodies, incredible musicianship, prophetic words, and flawless segues, the work is still one of the most significant and beloved albums of its genre.

First, the form of Thick As a Brick deserves attention. While many of Jethro Tull’s aforementioned contemporaries concluded their albums with a twenty-or-so minute track, Jethro Tull took it a step further by crafting a single forty-four minute piece. Not only did this bold approach allow the band room to experiment with density, arrangement, and continuity, but it set the stage for some of their latter output, including the album’s superior follow-up, A Passion Play. In an interview with Classic Rock Presents Prog earlier this year, Anderson recalls, “…it was more demanding and incessant because it was continuous music….it involved lots of repetition, lots of reiteration, lots of variation, [and] lots of development of themes in other guises.” Naturally, such a revolutionary tactic indelibly left its mark on the genre; in fact, many of today’s contemporary acts have released similarly structured songs, such as Echolyn’s Mei, Dream Theater’s Six Degrees of Inner Turbulence, and Phideaux’s Snowtorch.

On the surface, the album centers on a fictional schoolboy named Gerald Bostock who submitted a poem (which humorously explores the troubles of childhood) called “Thick As a Brick” to a contest. Anderson says, “The concept was a hard thing to sell… we all lived through the era of surreal British humour… The Americans found it more difficult because they found it hard to separate the fiction from reality…”

Of course, that’s just the superficial story behind the album; the real motivation for Thick As a Brick was an attempt to comment on the pretention of the genre and the misguided critical assessment of the group. Anderson explains, “… [Aqualung] was, in my mind at least, unreasonably described as a concept album, which I maintain that it was not.” He goes on to say that while some songs, like “My God,” were filled with religious commentary, the album as a whole was not meant to make any substantial statement. In response to such wild allegations, Anderson admits, “[I thought] ‘Okay, then we’ll give them the mother of all concept albums next time!’ So we did the completely over-the-top spoof concept album of Thick As a Brick.”

Looking outside of his circumstance, Anderson grants that Thick As a Brick also aimed to poke a bit of fun at progressive rock as a whole. In relation to the arguably convoluted, arrogant, and nonsensical fantasies some of his peers provided, Jethro Tull was quite grounded and traditional. Although he wasn’t exactly disinterested in the scene, he discloses that a focused mockery at others’ music was definitely there. “…We did see the slightly annoying spaghetti noodling of long, drawn-out instrumental passages, and we did kind of spoof that…there are some rambling, free jazz moments… that were more of a piss-take on some of the bands that were rapidly disappearing up their own arses.” Of course, there was always mutual respect amongst the genre greats, and Anderson is eager to concede that “…although we could have a little dig at them [King Crimson and ELP], you had to extend the hats-off credit to them for being extremely inventive…” In a way, then, it’s wonderfully ironic to consider how Thick As a Brick is actually superior to much of the work it satirizes.

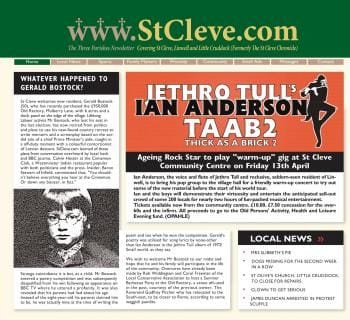

Outside of the music, Thick As a Brick was equally remarkable for its packaging. Essentially, the album was housed in an extensive faux newspaper entitled The St. Cleve Chronicle and & Linwell Advertiser (named after Bostock’s school). The attention to detail in terms of stories, sections, and structure is still impressive, as it exemplifies both Anderson’s dedication to making Thick As a Brick as monumental as possible and the growing artistry and ambition amongst the ancillary elements of the genre. He evokes, “I suppose it was a bit radical to do an album cover that was a newspaper… but, of course, [it] was very successful. In crude commercial terms it was a marketing dream, really.” Forty years later, it’s still ranked among the best, most elaborate album packaging ever.

Naturally, Thick As a Brick wouldn’t be nearly as worthwhile in the grand scheme of music if it didn’t pave the way for modern progressive rock. I recently spoke to a few of today’s most adored genre artists about their thoughts on the record. Guy Manning reflects, “[It’s] a brilliant album,” while Randy McStine (Lo-Fi Resistance) says, “Thick As a Brick belongs on every list of iconic progressive rock music. By poking fun at the scene around them, Jethro Tull ironically delivered one of the strongest albums to help define the genre.” In addition, Phideaux Xavier (Phideaux) claims that “this spoof is deeper and more moving lyrically and musically than the serious efforts of most bands,” and Rikard Sjöblom (Beardfish) states, “Thick As a Brick is an amazing album.” Finally, Tom Hyatt (Echolyn) recalls, “I remember the first time hearing Thick As a Brick. I was eight or nine… it was probably my earliest foray into progressive music. All the bumper car time changes and abrupt mood sings… taught me how visual an audio experience can be.” Clearly, progressive rock wouldn’t be what it is today without this record.

A New Look

Recently, a special 40th Anniversary edition of the album was released, and it definitely a proper commemoration. Houses in a hardcover book, the contents include a CD of the original album (remixed) and a DVD that contains several versions of the piece, including new 5.1 DTS and stereo mixes done by modern day genre king, Steven Wilson (Porcupine Tree). In addition, the book includes over 100 pages of supplementary material, which includes reprints of the entire newspaper, as well as glossy ads, pictures, interviews, and commentary. As for the music, well, it sounds better than ever. Every intense timbre and poetically poignant and playful word sounds lively and pristine; in fact, you’ll likely hear things you’ve never heard before.

Surprisingly, this special edition isn’t the only thing that emerged this year to celebrate Thick As a Brick. Far from it, actually, as this past April saw the release of its sequel, Thick As a Brick 2: Whatever Happened to Gerald Bostock?. Credited as an Anderson solo album, it connects both lyrically and musical with its predecessor in several places, including its opening and conclusion. Furthermore, the artwork of Thick As a Brick 2 is a subtle statement on technological advancement; whereas the first album was molded as a newspaper, this one sees The St. Cleve Chronicle as an online publication. In a way, one might conclude that “Thick As a Brick” is a 100-minute song that took roughly 40 years to complete.

A Revised Model

It’s easy to see just how important Jethro Tull’s original 1972 masterwork is. By pushing just about every musical boundary, the group firmly crossed over into the realm of progressive rock. Today, it represents not only a pinnacle achievement for Jethro Tull, but also a concrete example of just how adventurous and free artists used to be. More specifically, the recently released 40th anniversary edition is a perfect way to honor the record (let’s hope that A Passion Play sees a similar treatment next year), and its sequel is a surprisingly worthy follow-up. In the end, Thick As a Brick broke the mold and established what the genre could truly be; without it, progressive rock wouldn’t be the same.