“A day in the life changed my life,” declares P.P. Arnold. “The thought of being an Ikette or being in show business never crossed my mind.” It’s summer 2019, but London’s “First Lady of Soul” is thinking back to a winter afternoon in 1964 when a last-minute audition with the Ike & Tina Turner Revue marked Arnold’s foray into the music business. It also saved her from an abusive teenage marriage.

Fifty-five years later, Arnold’s first solo album of new material since 1968 reflects the kind of serendipity that’s guided her through the industry from the very beginning. Produced by Ocean Colour Scene’s Steve Cradock, The New Adventures of P.P. Arnold (2019) is an adventure in listening. The singer’s voice, tinged with both heartache and joy, delivers one thrill after another as she spellbinds listeners with a range of tones and styles. “That’s what I like about the album,” she says. “It’s eclectic — soul, pop, some beautiful ballads. You got the groove element in it.”

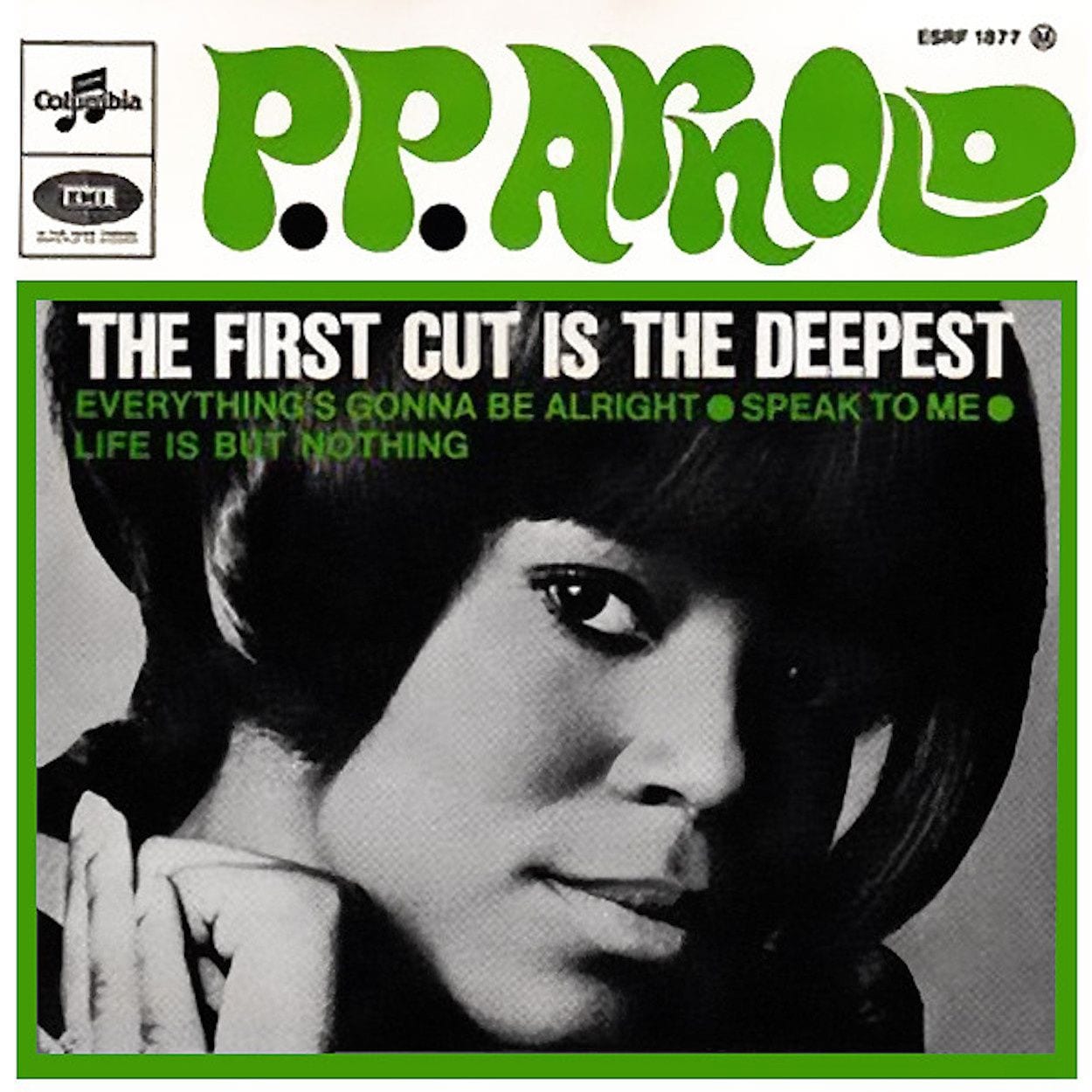

That stylistic range has long been the signature of Arnold’s career. Shortly after recording lead vocals on the Ikettes’ “What’cha Gonna Do (When I Leave You)” (1966), Arnold joined the Ike & Tina Turner Revue in London where they opened for the Rolling Stones. The singer’s friendship with Mick Jagger yielded her solo contract with Immediate Records, a label founded by Stones manager Andrew Loog Oldham. Within six months of leaving the Revue, she scored a Top 20 U.K. hit with Cat Stevens’ “The First Cut is the Deepest”, one of many highlights on her debut album The First Lady of Immediate (1967).

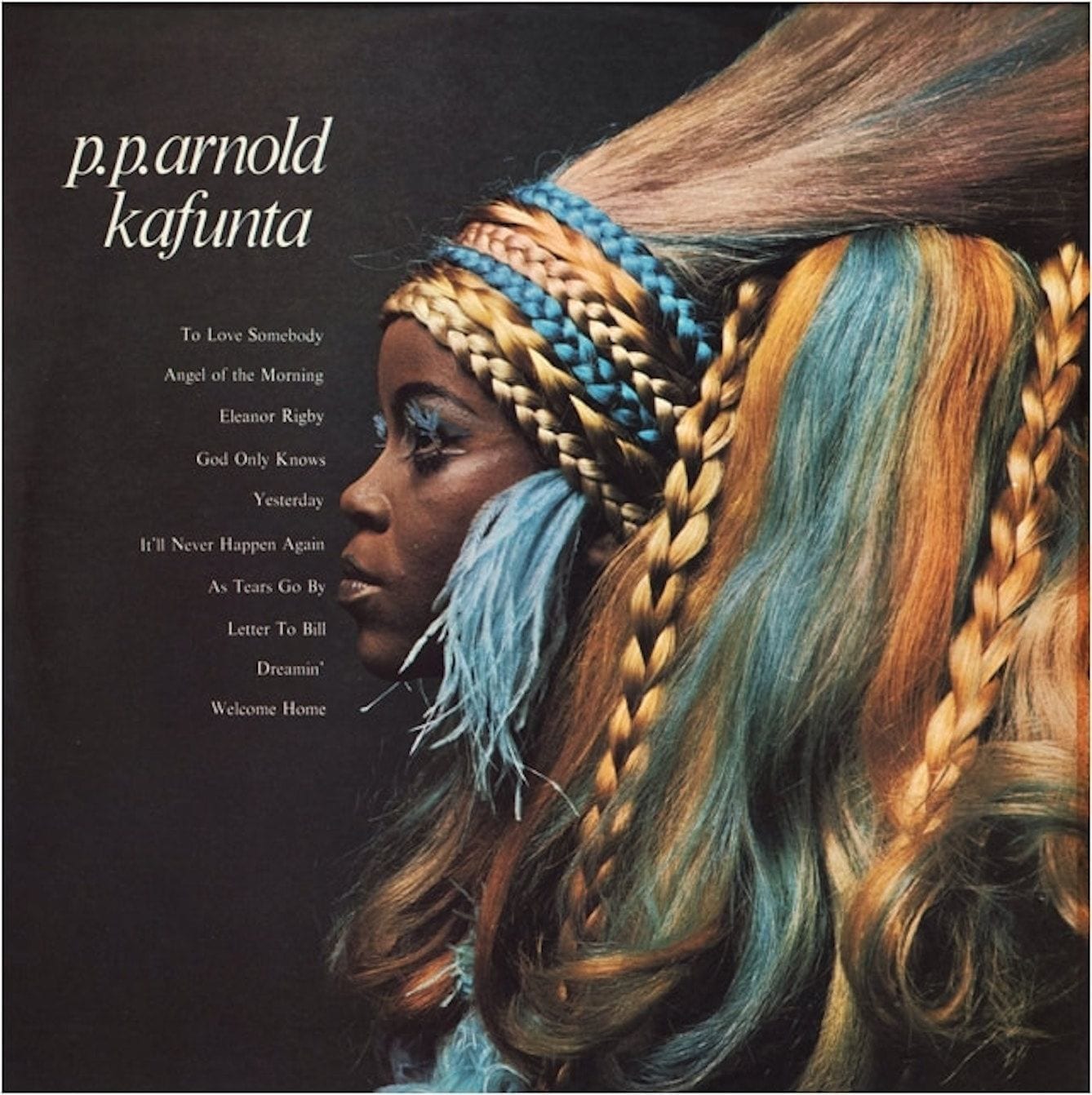

“I came out of the Civil Rights revolution in America into the rock ‘n’ roll revolution of the UK,” says Arnold. Her second album for Immediate, Kafunta (1968), spawned another Top 40 hit, “Angel of the Morning”, and secured her place as a centripetal force in London’s thriving music scene. Rock titans orbited the singer, whose gospel-inflected voice powered the Small Faces’ “Tin Soldier” (1968) as well as a duet with Rod Stewart produced by Jagger, “Come Home Baby” (1967). Arnold also struck a close friendship with fellow expatriate Jimi Hendrix who lived near the young vocalist in Montagu Square and inspired the name Axis, a band she subsequently formed with Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young guitarist Fuzzy Samuel.

Angel Wings by Zorro4 (Pixabay License / Pixabay)

After Immediate Records folded, Arnold met Barry Gibb and signed with the Robert Stigwood Organization (RSO), who managed the Bee Gees and Eric Clapton. While Gibb worked on crafting songs for Arnold, Stigwood placed the singer on Clapton’s tour with Delaney & Bonnie and Friends. “If it weren’t for P.P. Arnold’s compassionate nature and her big shoulders (that I cried on), I may well have not made it through that tour,” says Bonnie Bramlett. “Her and Fuzzy reminded me of my foundation — faith! The only thing bigger than her shoulders and her heart is her blessed voice. Can she sing? Like Peter can preach!”

Between 1969-1970, the next chapter of Arnold’s solo career held considerable promise with Gibb and Clapton each producing first-rate songs for the singer. Aside from one single, “Bury Me Down by the River” (1969), Stigwood shelved the tracks. Decades later, Arnold finally acquired the license to release the recordings she’d cut nearly 50 years earlier. The Turning Tide (2017) offers a fascinating glimpse of where the singer’s career was headed before industry politics froze her ascent to further solo success.

Similarly, many of the tracks on The New Adventures of P.P. Arnold stem from a moment when Arnold’s career was in full bloom. After scoring a massive UK hit with Ocean Colour Scene on “It’s a Beautiful Thing” (1997), she cut a number of demos with Steve Cradock, who produced her version of “Different Drum” (1998) on Universal. Though Arnold and Cradock had a good rapport, the remaining tracks never made it beyond pre-production. Two decades passed before Cradock and Arnold revised and expanded the material, shaping The New Adventures of P.P. Arnold into a lavishly produced and designed two-LP set that includes original songs plus Arnold’s takes on Bob Dylan (“Last Thoughts on Woody Guthrie”), Sandy Denny (“I’m a Dreamer)”, and a Northern Soul classic by Jaibi (“You Got Me”).

“P.P. Arnold is a wonderful singer with a distinct sound,” says trailblazing Philly soul architect Dexter Wansel, who produced Arnold in the mid-’80s following her comeback role in Andrew Lloyd Webber’s Starlight Express (1984). Indeed, The New Adventures of P.P. Arnold is a testament to Arnold’s resiliency. She’s survived personal tragedies, including the death of her daughter Debbie in 1977, and professional setbacks that could have permanently sidelined her career. Instead each challenge only emboldened Arnold to sing with more power, passion, and authority.

On the eve of her “new adventure”, which includes a UK promotional tour beginning in October, Arnold spoke with PopMatters about the 20-year history behind her latest album while retracing her career from the Ikettes to meeting Mick Jagger, working with Barry Gibb, and opening her heart to miracles.

Congratulations on The New Adventures of P.P. Arnold. I’m so thrilled for you because this album’s been a long time coming.

It’s been a long time … [sings] “but I know, a change is gonna come”. I knew it was coming, that’s why I never gave up.

You’ve been so prolific over the years, working with so many different artists, from Peter Gabriel to KLF to a collaboration with the Blow Monkeys’ Dr. Robert on Five in the Afternoon (2007). What kind of musical statement did you want to make for your own album?

For me, it’s always about the songs. Steve and I were a good fit. He really understood my roots and where I had come from, not only my gospel roots and my R&B roots, but my roots as “P.P. Arnold”, as this English soul queen that was produced by all of these English producers who gave me this unique sound. The Northern Soul scene are my hard core fans, all the mods, so we wanted to do music that was going to make them happy and we wanted to do stuff that was going to make us happy.

Steve and I actually put the ideas together in the ’90s — writing, demos, production — and then the project got shelved for awhile. Ocean Colour Scene had a lot going on at that time. We both went in different directions. Roger Waters saved me! I thought I was only going to do one tour with Roger and then I ended up touring with him for about ten years. You never know what’s going to happen, do you?

I got a call from Steve back in 2016 or the end of 2015. He was setting up a home studio. He’d come across the tracks that we had started. He wanted to know if I’d be up for finishing the project. I said yeah straight away. Steve brought a couple of songs to the table, with a couple of good indie writers, Steve Grizzell, who co-wrote “Baby Blue”, and Jake Fletcher, who wrote “Daltry Street”. At first, I didn’t know if those tunes were right for me because I thought they were too pop. As everybody gets old, they start singing jazz, they go back into blues, or they do standards. I didn’t think that I fit into that mold because even though I’m the same age as all my peers, I still have this young spirit. Steve said, “The songs are great. Listen to them.”

“Baby Blue” opens the album. earMUSIC also released it as the album’s first single back in May. What appealed to you about that song, specifically?

I don’t really know what it was that drew me to “Baby Blue”, but I just had this strong connection to it. I knew it was about a young girl who had been through some kind of sad thing. I could definitely relate to that from my teen years. Then I found out that the song is about this young girl who gets pregnant and her parents make her give up the baby. She’s in this abusive relationship and just goes into a deep depression. When I found that out, I thought, Wow how is it that this song came to me? It was like “First Cut Is the Deepest” — I had lived that. On “Baby Blue”, I had lived that kind of experience as a young girl. I just felt her sadness. Steve was right — I can relate to the song.

“Daltry Street” is about a street up in the north of England where Jake grew up. When I sat down and listened to it, I realized that “Daltry Street” was just like the street that I grew up on, 117th Street in Los Angeles. The city ran a freeway through there and tore apart that community. The whole support system that I had grown up in was gone and it wasn’t there to protect everybody when everything changed so drastically, with all of the gangs. That whole neighborhood-community vibe was gone. “Daltry Street” had a similar story.

I know your relationship with Steve goes back to Ocean Colour Scene’s Marchin’ Already (1997) album. How did you first meet Steve and the band?

I was playing Erzulie in the West End version of the musical Once on this Island. We toured the provinces. We were in Birmingham before we came into London. I was called to the stage door one Saturday afternoon, which was the last night of the show in Birmingham. We were going back to London that evening. I went to the stage door and there was Steve and all of them standing there with flowers! They introduced themselves to me. They had a studio that was close to where the theater was. They wanted me to go with them to the studio that night but I had to go back to London. That was the first time that we met.

Then, there was a Small Faces tribute album. They were getting the respect and due that they deserved. I did a track with Primal Scream on that album, “Understanding”. Ocean Colour Scene did “Song of a Baker”. That’s the second time we came into each other’s vibration. I recorded “Travellers Tune” with them and we did the duet “It’s a Beautiful Thing”. We performed on TFI Friday. I remember going to Hollywood with them around the same time.

Steve and I then recorded a version of “Different Drum” that was released on Universal. It got some airplay but the song didn’t get the exposure that we felt it deserved. We decided to record it again for this album so that we had control over it.

When you speak to Steve, please tell him that “The Magic Hour” is appropriately titled because that song is magical. The combination of the strings, the horns, the flute, and your voice is enchanting. What does that song evoke for you?

That’s Steve’s song so he would be the person to say exactly why he wrote it, but what it evokes for me is being in love. You wake up in the morning and even though the person is not really there, the love that you have for that person is with you.

Everything on that track just clicks together in a beautiful way …

… and it’s so simple! It’s so full of light. The hook is just fabulous. It’s summery too. I don’t know if they’re going to release it for the summer but it has a nice summer vibe about it. “Baby Blue” and “The Magic Hour” have that whole ’60s vibe happening.

Your take on Paul Weller’s “When I Was Part of Your Picture” and “Shoot the Dove” are also among the album’s highlights.

I love Paul. We’d demoed “Shoot the Dove” back in the ’90s. Paul liked my version of it, so we decided to do it properly. While we were recording, Paul presented me with “Picture”. We did it at Paul’s studio. He did the background vocals on the end of the track.

“I Believe” is a great, moody piece. The line in that song that stood out for me was “I believe in change, time to rearrange”. What are some moments in your life that you felt needed re-arranging?

Everything needed rearranging! I wrote that song with my son Kojo around 1990. In the ’80s, I had an accident. I was out of the scene. I came back with the Beatmasters and did stuff with KLF — all of that dance stuff — always trying different things. When I did those tracks, I was the only live thing on the track! KLF? I brought Katie Kissoon with me. Katie and I are the Mu Mu Choir. The “3 A.M. Eternal” track? That was me. They asked me to vibe on their thing, so I gave them that vibe, but they didn’t do me right.

Still, the industry wasn’t into me. It was a whole ageism thing. When I look back on the ’90s, I was still young, but for the industry, I was too old. I couldn’t get a record deal. I got really upset. I was smart enough to set up a 16-track studio at home, so I just decided I was going to make my own record.

Kojo’s just a great great musician. He’s always had so much talent. “I Believe” and “Hold Onto Your Dreams” come from that whole session of 1990 stuff that Kojo and I did together. We originally did them as dance tracks. All the groove, all the music, everything you hear that Steve produced is all Kojo’s groove. I wrote the lyrics over it. “I Believe” and “Hold Onto Your Dreams” are about faith and about wanting the world to be a better place and finding the love that will help us make the changes that are needed right now on this planet. I’m really glad that I’m getting the opportunity to perform those songs now.

P.P. Arnold and producer Steve Cradock. Photo: Gered Mankowitz / Courtesy of GreenGab PR

“I’ll Always Remember You (Debbie’s Song)” is such a touching tribute to your daughter. I think one of my favorite couplets is “Even the flowers and the trees responded to your laughter / they’re lucky to have you in the hereafter.”

The lyric and melody just came through me. After losing Debbie, I had that melody forever. I had recorded it before with a guitarist named Tony Rémy. It had a jazz vibe to it. I played the track for Steve and he really liked it but he wanted to produce it in a more classical way.

I was in Spain when they actually recorded the track at a cathedral. That was a bit of a problem for me when it was time to record the vocals. The organ was beautiful, but, to me, it sounded sorrowful. I wasn’t really feeling that. The whole idea of “I’ll Always Remember You” was for people to know Debbie’s character. She was such a beautiful little girl with all of this loving energy. Everybody wanted to be with Debbie because she was so much fun.

I always said that if I had the chance to record another album, I wanted Debbie’s song to be on it, but I wasn’t going to put it on there if it didn’t sound right to me. Thank God for the technology that we’re able to use to make things right. I got Steve to take out some of those bottom layers of that organ. We got there in the end! I just really love it.

I knew that Debbie would love the whole classical element of it. She was just everywhere when we were recording that song. She came through in my dreams. She’s with me everyday. I even think that her energy is what’s helping me to be out here at this age and still have my young spirit.

I wanted to ask you about a song you wrote with Steve, “Finally Found My Way Back Home”. There’s a great line in there. “Jimi whispered in my ear” …

No, it’s “gently whispered in my year”.

Oh, gently! [laughs]

You thought it was Jimi Hendrix, right? Yeah, he whispers in my ear occasionally. It’s nice to be able to have some really beautiful visitations from Jimi from time to time. They’re always very special. Once in awhile, I’ll have a wonderful dream. It’s real. I believe in all that — visitations — but Jimi wasn’t whispering in my ear in “Finally Found My Way Back Home”. That was my true self whispering in my ear, the spirit inside of me.

Forgive me for mishearing the lyric!

It’s a good interpretation. [laughs] I wrote “Finally Found My Way Back Home” when I first met Steve. I went up to Birmingham where we first started doing the pre-production demos. He went off to do a gig and I was just messing around with the music that he had. I put my lyric on top of it and it just worked. “Finally Found My Way Back Home” is all about me getting back to the roots of who I am after going through a lot of changes — exploitation, tragedy, disappointments — and finding my true self that had saved me all those years through all of that darkness.

The album has a few interesting covers, including the late Sandy Denny’s “I’m a Dreamer”. Were you acquainted with her back when she was in Fairport Convention?

No, I didn’t know Sandy. I came back to the states in 1975 to do that record with Fuzzy and then I lost Debbie in ’77, so we just kind of missed each other. When I came back to the UK in ’83, I met a lady named Miranda Ward who was a very good friend of Sandy’s. She told me about Sandy. When they were doing the tribute tour for her, I was called and asked if I would be interested in singing some of her songs. I did the tour with all of these folk artists that was just absolutely fabulous. I was singing Sandy in a soulful way. Even though they were folk songs, I put my own stamp on them.

I also recorded a song that I think she had written when she was in the states, “Take Me Away”. It had a really great gospel vibe. I recorded that just to kind of promote myself while I was doing the tour. I think they recorded the gigs at the Barbican, but nothing was released. I was talking to Steve one day and he asked me if I knew about Sandy Denny. He was really into her. I told him that I had done this tour. He was like, No way! We decided to record “I’m a Dreamer”.

You sing such an inspired version of “You Got Me” by Jaibi, which I understand is a Northern Soul favorite. Were you familiar with the song before you recorded it?

I wasn’t familiar with it until Steve played it for me. It was one of the first pre-production demos that we did back in the ’90s. Working with Steve has been great because those guys are on it. I love the tune that he wrote, “Still Trying”. It took me back to doo wop and the early-’60s. I have brothers who sang and it reminded me of that time.

The whole Northern Soul scene started happening pretty big around the mid-’70s and I wasn’t in England at the time. I missed that scene as it developed. I grew up surrounded by the blues but when we were kids, the blues was like old folks music to us! [laughs] It wasn’t until I got back to England in the ’80s that I found out about Northern Soul. I got a total education when I arrived. “Everything’s Gonna Be Alright” [from The First Lady of Immediate] was this big Northern Soul classic. It was selling for incredible money. I never got paid for any of it!

Of course, a lot of rare Ike & Tina Turner gems are also beloved by the Northern Soul community. How familiar were you with Ike & Tina before you, Maxine Smith, and Gloria Scott became Ikettes in 1964?

I knew who Ike & Tina Turner were because you’d see them on the Dick Clark show and all the TV shows they were doing. They were quite popular, but I never had a desire to be in the music industry. It wasn’t my direction at all. I just grew up singing in church.

I said a prayer one Sunday morning and asked God to show me a way out of this abusive teen marriage I was in. I was working hard — doing all my laundry, cooking, and getting ready for the week ahead for my two jobs that I was working. About an hour later, the phone rang and it was Maxine. She was an ex-girlfriend of my brother’s. She knew me as a singer but from the church. I had met Gloria with her before on one occasion when I’d snuck out of the house and done a session. Maxine called me and said, “Pat, you’ve got to help us out again. We’ve got an audition with Ike & Tina Turner to be Ikettes.” I thought, I can’t go with you. David (my husband) isn’t going to let me go anywhere. She said, “We’re coming to get you” and hung up the phone.

About half an hour later, Maxine and Gloria were on my doorstep. I lied and told my husband that I was just going to the shop for something and asked if he would babysit. I go out of my house and there’s Jimmy Thomas driving Ike and Tina’s Brougham Cadillac at the end of the curb where I lived. I jumped in the car and said, “Hurry, hurry. You got to go. If my husband sees me getting in this car, I’m in big trouble.” Jimmy goes, “You got a husband?” He started laughing because I looked about twelve years old! “Yeah, I got a husband and two kids. I’m gonna be in big trouble if you don’t drive out of here.”

We drove off and the next thing I know, I’m in Ike and Tina’s living room singing the harmonies on “Dancing in the Street”. They had been auditioning girls all week because Robbie [Montgomery], Jessie [Smith], and Venetta [Fields] were leaving. We were the last set of girls that they auditioned. They liked our young look because we were the personification of that kind of new Motown / go-go girls vibe. We could do all the latest dances.

When we finished, Tina goes, “Girl, you got the gig!” I thought, Oh no, not me. I just came to help them out. My husband doesn’t know where I am. He’s gonna kick my ass because I should have been home two hours ago. Tina says, “Well, just so you don’t get your ass kicked for nothing, why don’t you ride up to Fresno with us and at least see the show?” The day had already taken on a life of its own. I thought I might as well go because I never got a chance to do anything or go anywhere. I’d totally blown my teen years. The obedient wife became a bit of rebel and went up to Fresno. [laughs]

I went to Fresno and came back at six o’clock the next morning. Sure enough, as soon as I put my key in the door, my husband was there and he hit me in the head. I remembered my prayer. I’d asked God to show me a way out and suddenly I had this way out. That’s how I connected with Ike and Tina.

Wow, what a story! It’s fascinating to hear you sing “Though It Hurts Me Badly” more than 50 years after you first recorded on The First Lady of Immediate. I’d say it’s even more powerful than the original. What inspired you to write it, initially?

[laughs] That song is quite deep. “Though It Hurts Me Badly” is the first song I ever wrote. It’s about my first interracial relationship. I had come out of this whole abusive marriage. I had a guy that I was seeing in the Ike & Tina Turner Revue, Gabe Flemings. He was protecting me from Ike, actually. We played the Apollo Theater before we flew to England to start the Rolling Stones tour. I caught Gabe with another woman so I quit him when I landed in England.

When I came to England, I was a very shy, introverted young woman. I hadn’t had a real teenage life at all because of what had happened to me. I came from a very segregated way of living in America and then suddenly there I was, this little black girl from Watts, hanging out with the Rolling Stones in England. For the first time in my life, I was free.

I came out of the Civil Rights revolution into the rock ‘n’ roll revolution of the UK. At that time, everybody was so into the music, so it was great not having to deal with that racism vibe that was going on in America, but it was still taboo for me and taboo for the person that I was seeing at the time. “Though It Hurts Me Badly” is me facing that whole thing where you’re hanging out but you know the guy’s not taking you home to meet his mama.

Why did you revisit “Though It Hurts Me Badly” for The New Adventures of P.P. Arnold?

Everybody liked it. Paul Weller, Steve, and every musician who I met who knew of that song from The First Lady album all liked it. It didn’t really have any exposure back in the day. It was just a track on the album. Steve did a fabulous production. All of my songs have really strange melodies because I don’t play an instrument. They’re inspirations that come through me. As a singer, I hear melodies, but I didn’t know any of the musical rules.

Who were the other Ikettes in the Revue when you went to England?

Ann Thomas and Rose Smith. They were in London with me. Maxine and Gloria left after that first tour. They were really angry at me because I didn’t leave. Ike was fining us for stupid stuff and they had just had enough. We had all planned to leave together, but I couldn’t leave. I had two kids. I’m still in contact with Gloria Scott. She’s stayed with me in Spain. She always says, “Pat, you made the right decision for yourself.” It was really hard without Gloria and Maxine. When they left, I became the lead Ikette because Ann Thomas was Ike’s other woman. She couldn’t sing, but she looked good. Ann got fined if she sang!

“Don’t sing Ann, just dance!”

That’s right. Just look good and mime. Rose was a really pretty girl. She was all very “Hollywood”. I don’t think I was Tina’s best Ikette. I was a good singer, but I wasn’t as cool as the other girls, I guess you would say. They were all into show business. I was just trying to take care of my babies. I got the gig and did my gig.

Claudia Lennear explained to me how she reached a plateau being an Ikette. Similarly, Joshie Jo Armstead, one of the original three Ikettes, left because she felt there was no room to grow in that role.

No, there wasn’t. It was too controlled. All we did was work. I wasn’t even thinking about growing or becoming a solo artist. None of that mattered to me. It was just a gig to me, I’m going to be honest. I didn’t have the ambition to be part of that celebrity thing. I didn’t get caught up because I had my babies. That might have been my downfall … and that might have saved me.

When we toured with the Stones, I became friends with Mick Jagger. I just could not get over this white guy with these big lips who walked like a black man! He used to make me laugh trying to do the mashed potato. He would come to our dressing room and we’d show him all of the routines. Suddenly, I had come out of my shell and was having fun. Ike was not happy about this. He was giving me a hard time because Mick would send a limo to pick me up from the hotel and take me to the gig. Afterwards, we’d go to the discotheques. Ike was fining me for absolutely anything — if I had a run in my stocking, I got fined. If I was 30 seconds late, I would get fined.

I just casually said to Mick that I thought I was going to leave the Revue. I didn’t want to be an Ikette any longer, not just because of me getting fined, but the whole thing of having to watch Tina go through what she was going through. It was Tina who had turned my life around. She had saved me from abuse, so I was very sensitive to what she was going through.

How exactly did you make the transition from the Ikettes to becoming a solo artist?

After the Revue finished touring with the Stones, we stayed and were doing our own tour. On a day off, Mick invited me to go to lunch. We were walking in Regents Park and he made me this proposition. He said that his manager Andrew Loog Oldham had this record label (Immediate) and they were interested in me staying in the UK and signing with the label. I was shocked! The deal was that Mick would produce half of the album and Andrew would produce the other half.

Mick knew I had two kids and my kids were with my mother. I said, “I’ll have to call my mother and talk about this with her”, which I did. My mom said, basically, if I wanted to stay, she would look after the kids, but she wouldn’t look after the kids for longer than six months. In six months, if nothing had happened, I would come home. In six months, if something happened, I would get my kids. In six months, I had a hit with “The First Cut Is the Deepest”, so I went home and got my kids.

Where did you first hear “The First Cut Is the Deepest”?

At a listening session. Back in those days, artists weren’t really writing that much. All the publishers had their writers and the writers would send their songs to various artists. Mike Hurst had given the song to Andrew for me to listen to. I loved it. Everybody loved it. It was as if Cat Stevens had written that song for me.

I’m doing “First Cut” onstage again. Through the years, I must have sung it 100,000 times. It’s developed and it’s been many different things. We slowed it down and did a soulful, blues kind of version of it. Doing it with Steve, we’re taking it back to that uptempo, Northern Soul vibe that I put on it in the ’60s. I have to learn to sing the song over again because I’d changed it. I didn’t even remember how I originally sang it until I listened to it. I thought, Yeah, that’s really cool! I’m gonna do that again.

Cat Stevens says that my recording is the definitive version of “First Cut”. It’s his song. If he can say that, then what an honor! I think my song was so sincere. It was so heartfelt. Sometimes people cover a song and they do their own thing on it but that was my story. If people sing the song because they like the song, and it’s a great song, that’s one thing, but when you sing a song that you’ve lived, then that’s another expression.

Earlier, you mentioned Once On This Island, but I want to ask you about Starlight Express since 2019 marks the 35th anniversary of the original London production. Back in March, I interviewed Ray Shell here in New York for the anniversary.

Yes, he told me! I saw him after that.

It was quite a series of events that turned Ray into “Rusty the Steam Engine”, so I’d love to know how you became “Belle the Sleeping Car”.

[laughs] I really identified with Belle. She had been a grand car, but then they put her on the heap. It was like me, coming back after having been through the ringer. I knew Andrew Lloyd Webber from recording Jesus Christ Superstar (1970). I didn’t do the musical because I was pregnant with my son Kojo at the time, but I’m on the recording. Doris Troy, Madeleine Bell, and myself did a lot of the overdubs. We put the meat on top of the choir stuff.

Starlight Express was years after Jesus Christ Superstar. Andrew was a big impresario at the time! I’d just come back to the UK after being in the states. I found it really hard coming back to the UK without Debbie because my kids grew up in England. To come back to England without her was really really hard. I didn’t have any money but I had a friend who knew an agent that was putting people forward for Starlight Express.

I got an audition. I went to the audition and I sang “Everything Must Change”. They told me Andrew was “besotted” with my voice and that I got the part. I had the right sound for Belle. All I had to do was pass this rollerskating audition. I used to skate at the skating rink but I couldn’t really skate. I could hang in there but I couldn’t do spins or three-point turns or any of the stuff we needed to do for Starlight Express. Everybody realized that at the audition! I said to Andrew, “Give me three weeks to brush up on my skating”.

I bought some skates and I went to the Old Street Skating Rink every single day and night. I met this guy who was the British world skating champion. He was teaching rollerskating at the rink and put me through my paces. I went there and I worked hard. I just didn’t know how I was going to do it. I could not get that three-point turn, which was really important.

One day I was trying to get that three-point turn and I fell on my coccyx bone. I was in agony. I was living in Pimlico and the skating rink was miles away. I rode the train home. I cried all the way. I was in so much pain. When I got to my flat, I went inside and took those skates off. My spirit told me to go back. I listened. I picked my skates up and I went all the way back into town. That was the night I learned how to do that three-point turn. When I went back three weeks later, everybody was shocked. Not only could I do three-point turns, I could do spins. I was a great speed skater so I got the gig. That’s where I met Ray.

Since you worked so closely with Ray, how would you describe the quality of his voice?

It’s just incredible! I love Ray. He’s such a talent. He’s got a distinctive style. The quality comes from his expertise. He’s a vocal teacher as well. Our relationship was just beautiful and it still is. We had to speed skate in the show. Ray was such a scaredy cat. I was always encouraging him — “Come on, we got to do this!” We got so good that we had to wait in the tunnel to let everybody else go by! We went so fast. [laughs]

Theater is Ray’s life and his love whereas for me, I never grew up with that technique. I never “learned” how to sing and neither did Ray because he’s a very natural gospel singer too, but he was very disciplined with all of his theater training. He found his own style. He’s just an amazing singer. He’s got such a great technique.

I didn’t really learn about technique until I started working with Roger Waters and started doing the Seth Riggs technique. Basically, I worked with Seth a couple of times and I worked with his daughter when I’d be in LA. Then I found Lucy Phillips who I worked with London. I mostly work with Lucy via Skype.

When I worked with Roger, I wanted to do “Great Gig in the Sky”. I worked really hard to stretch my range to do that tune. Roger had actually given me the song but politics were going on. If I had done “Great Gig”, my tone and everything would have taken it somewhere else. I really miss working with Roger because you rehearse for two months. You rehearse so much that you think, When are we going to do the gig? [laughs]

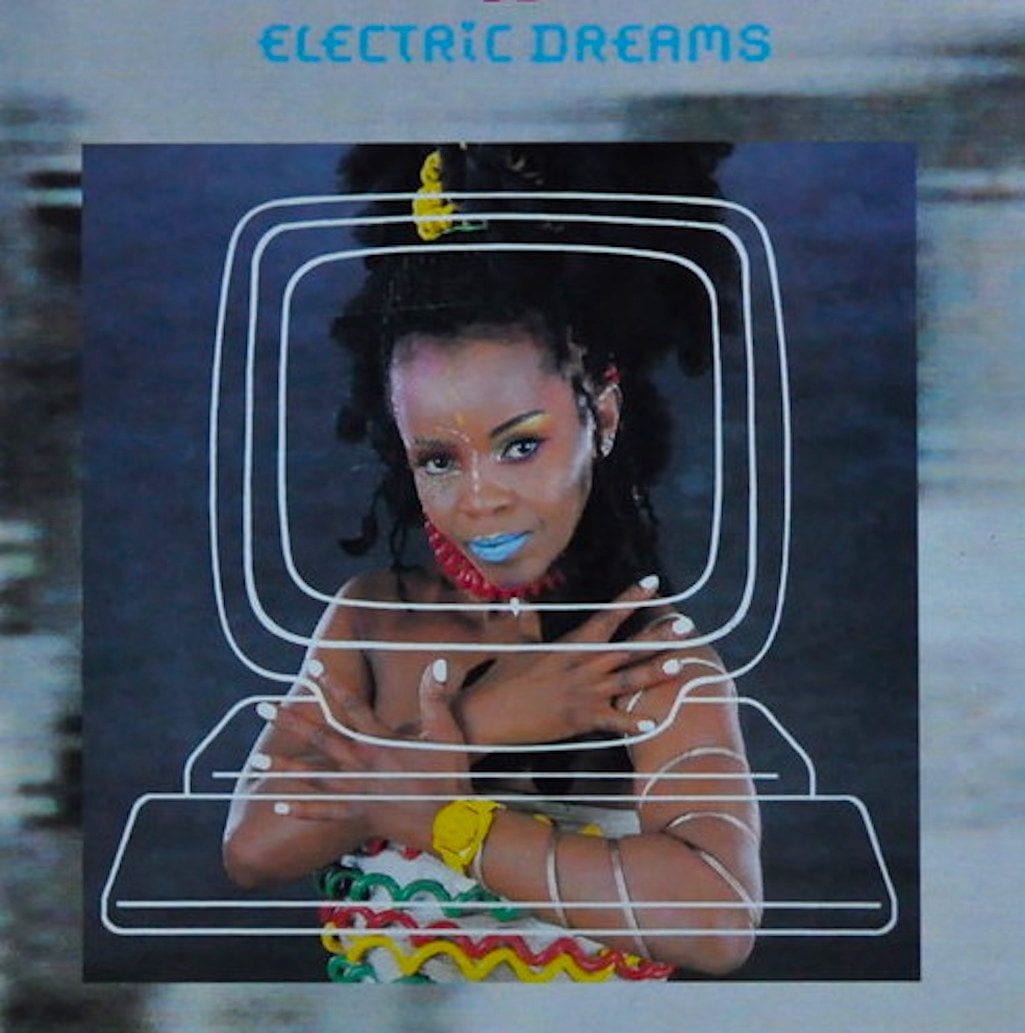

I’d love to discuss a song you recorded the same year you opened in Starlight Express, “Electric Dreams” on the Electric Dreams (1984) soundtrack. That song has such an interesting combination of talent between Don Was producing it, Boy George co-writing it, and Peter Frampton playing the guitar solo.

That’s a really cool tune. That whole period for me … I’m getting goosebumps just thinking about it because I came back from such tragedy. I was able to sing again. After Starlight, everything was happening. I signed a deal with 10 Records. It was great working with George doing “Electric Dreams”. We had so much fun. He did all of my makeup. It was nice to be part of a whole happening thing because he had this young vibe and energy. To come back out of nowhere and be able to go in the studio with Boy George and Don Was was pretty cool.

Did 10 Records make that connection for you with “Electric Dreams”?

Yes, definitely. After I got into Starlight Express, it was Steve Lewis who helped me get the deal with 10 Records. He was at Virgin Music. Before he hooked up with Richard Branson, he was doing some stuff with Fuzzy and me so I knew him from that period. He was a friend of mine. He was a real P.P. Arnold fan. He helped me get back on my feet.

I also worked with Dexter Wansel during that 10 Records period, but 10 Records didn’t really know what to do with me. They wanted me to sing on their tracks. I remember I would come from the theater and go straight into the studio to record at night. The whole scene had changed. I didn’t have any kind of understanding about the technology that was happening, but it was a good time!

You’ve had so many different champions over the years. I’m so glad that you were able to release The Turning Tide a couple of years ago so we could finally hear the music you did with Barry Gibb and Eric Clapton for the Robert Stigwood Organization (RSO) back in the late-’60s. I read the essay you wrote for that album. It took so much tenacity to get that music released. What kept you going to see that project through?

Just not giving up and always having hope. Everybody got ripped off in the ’60s but if you made it through the ’70s, that was it. Everybody who made it in the ’70s is like a higher echelon of the industry now. That whole RSO period of working with Barry and Eric was the next stage from Immediate. Had that music been released then maybe I would have been able to make it through the ’70s with my peers. Because that music wasn’t released, I got lost. The ’70s was such a hard time for me.

When you’re part of a musical family and things don’t work out, everybody goes their separate ways … and I still didn’t know how to get through the industry. When Immediate went bankrupt, I thought, Where do I go? Everybody else knows that whole scene, whereas I had two kids with me. I wasn’t somebody out there networking all the time.

Meeting Barry was another blessing. I met Barry through Jim Morris, who was my boyfriend who I later married. Barry was best man at our wedding. Jim worked with Robert Stigwood. He and Barry were really close so when Barry found out that Jim was seeing me, he wanted to meet me because he liked my version of “To Love Somebody” that I recorded on my second album. We were both at a crossroads. Immediate Records had split up. Barry and the brothers had split up. He wanted to keep recording. He liked my voice so he just started writing songs.

The title track to The Turning Tide is such a compelling recording …

…. [sings] “I only know that I / am reaching too high. And who are we to touch the wind / and say our ship is coming in.” Songs run through Barry Gibb like a river. Barry wrote “The Turning Tide” and those songs with me in mind. I recorded them before the Bee Gees.

Stigwood didn’t want Barry working with me. He wanted Barry to get back with the brothers — understandably — but Barry was calling the shots. He was the big brother. He was the one with all of the charisma. Barry insisted that he was going to work with me. He had a plan. The Bee Gees had signed with Atlantic and Ahmet Ertegun was in town. Barry and his wife Linda gave a dinner party and invited Ahmet. Stigwood was there as well. Barry and I sang acoustic versions of the songs that we had been working on. Ahmet said, “Robert, you haven’t signed this girl yet?” Robert said, “Oh yes, yes. We’re putting the paperwork together right now.” Robert signed me when he realized Ahmet had that interest. Barry’s plan worked! That’s how we got a chance to start recording and going in the studio.

Photo: Gered Mankowitz / Courtesy of GreenGab PR

Years after those sessions with Barry, you recorded “Will You Love Me Tomorrow” (1980) with Andy Gibb. I almost tear up when I think about how he passed away at such a young age. That was one of the last studio recordings he ever did.

You keep talking to me about these situations and the chill bumps just come up! Barry and Linda had this house in Eaton Square. That’s where we rehearsed and put everything together. We spent so much time working on the songs before I actually went in and started recording them. Andy would be out in the square playing football with my son and my daughter. He was a little boy.

When Debbie passed away, I have no idea how Barry found me. I got a telephone call from Dick Ashby inviting me to go to the premiere of the Sgt. Pepper (1978) movie. They sent a limo for me and my brother Kenny who went with me. My limo gets to Sunset Boulevard and turns right. The Bee Gees happen to be in the limo that’s right behind my car!

My brother and I get out of the car. We walk down the red carpet. Nobody knew who I was. [laughs] The next car is Barry and Robin and Maurice. They get out of the car. Barry sees me and says, “Pat!” Everybody’s running towards me saying “Who’s that?” That was the first time they had seen me in all those years. It was quite an emotional thing because they knew my kids. Losing Debbie was so deep. I was in shock, really. I was grieving hard and then suddenly here I was in this limo and back in the industry again.

Afterwards, we went to the Beverly Hills Hotel where we were staying. Barry was there and he said, basically, if I could get to Miami, he’d be interested in finishing the album. When I got to Miami, the Bee Gees split up again because Sgt. Pepper didn’t do well so they were still having problems. Everybody wanted to work with Barry. I had no management or support system, so we weren’t able to finish the album, but he asked me to do “Will You Love Me Tomorrow” with Andy. What a beautiful version of that song. It was recently re-released in the UK on The Very Best of Andy Gibb (2018). They used that track to promote it, which was good for me! That was around the same time that The Turning Tide was released in 2017.

In a way, The Turning Tide has only bolstered the anticipation for The New Adventures of P.P. Arnold. I think what’s working in your favor is that you could work this album for any number of years and it will still sound fresh.

I hope so. I’ve done the work. I’m doing the work. I’ve stepped up to the plate. I’ve got a great team. I think it’s a record that stands out on its own. It’s an eclectic mix of a lot of great songs. Steve has just done an amazing production. Not only does the record sound good, it looks good. They’ve done such a fabulous job with the artwork. It’s a beautiful album. For me, I feel like it’s in the hands of the universe. I open my heart to miracles.