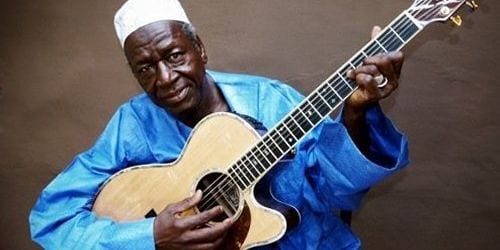

Boubacar Traoré is one of those Malian musicians that the outside world has heard of — not as famous as the late Ali Farka Touré with his Mali blues or Toumani Diabaté with his kora, but known nonetheless, a survivor and a constant low-key presence. Born in 1942, he taught himself the guitar — in another version of this story he learns to play from his brother — but he’s good enough to be employed by clubs, and he has a spot on Mali radio every morning performing his song “Mali Twist”. All of his money at this point comes from performances, and he never records an album. Then he drops out of sight into a series of random jobs until the late 1980s, when a near-revival is sabotaged by the death of his wife Pierrette, a disaster which bereaves him so deeply that he moves to France. In 1990, Traoré releases his first album, and a career in music begins to reassemble itself around him.

Today, he tours and records. You can find online footage of him performing in Brussels, in Trumansburg, New York, and in the capital of Slovenia. His singing voice is less juicy on Mali Denhou than it was in the ’90s, and he sounds quieter overall, more passive and restrained, or perhaps more subtle, working the surface of the music in smaller ways instead of going for the chorus hook. His 2000 recording of one of his 1960s hits, “Kar Kar Madison”, has a great hook, very simple and irresistible, and if you haven’t heard the song yet then track it down. If it catches you at the right moment you’ll be humming for days. You’ll also probably want to listen to Mali Denhou, and in spite of the fact that you won’t find a similar hook here, or that earlier wry combination of dryness and exuberance in his voice, you still might be beguiled by the sound of a man in no hurry, and by his patient guitar, which is less imperious than the guitar of Touré. You may appreciate the way he seems to parse the instruments around him, mainly the harmonica and the balafon xylophone, and by the way he manages to almost retreat behind them, as if they’re the stars of the song, not him.

The coiling mobius strip of a Mande sound that started off in a kora like Diabaté’s and made its way into a blues style like Touré’s has been incorporated into his music as well, and there is a feeling of things being patterned and spun around in pentatonic circles. There’s that strange sense of flatness and zen calm somehow taking place simultaneously with neverending activity. The tone of Mali Denhou is gradual and broad, and the final song, which runs for six and a half minutes, seems willing to keep going forever without coming to any particular end. Finally, he stops singing, there’s a last trickle of noise from the guitar, and then a ringing silence. To endure is the message or underlying message here, to endure and endure, as if he’s gone through everything, career disaster, the death of his wife, and now this is what he knows how to do better than anything else: he endures.