Leanne Shapton’s Was She Pretty? is not a comic in a traditional sense. No talk balloons and caption boxes, no panels and gutters, not even recurrent characters or a plotline. Shapton instead offers variations on a single theme, a litany of ex-lovers and their lingering presence in new relationships.

The table-of-contents features over 50 first names, the vast majority women, their status as ex- or current girlfriends unmarked, because each couple is also a triangle. Josephine and Robert plus Robert’s ex, Alicia. Jennifer and Richard plus Richard’s ex, Cassandra. Alicia and Cassandra remain not only as memories for Robert and Richard but as new, evolving conflicts for Josephine and Jennifer. Most of Shapton’s drawings are of women, with about a dozen of the one hundred or so images featuring men, making women both the primary haunters and the haunted.

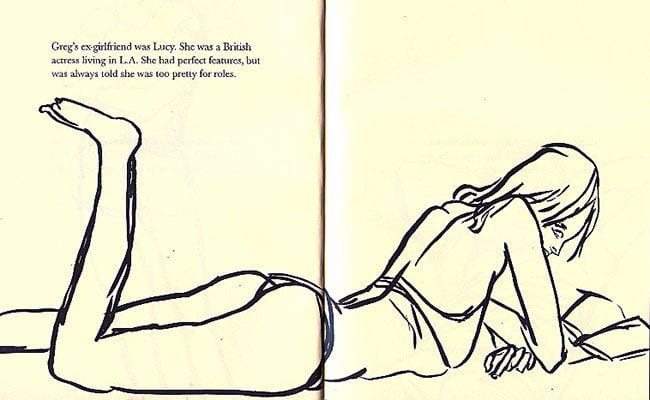

Shapton’s form reflects her subject well. Each two-page spread is a kind of couplet: words on the left, drawing on the right. The words, usually one or two sentences, are typeset and centered on otherwise blank pages. The drawings are ink sketches, executed in a quick, gestural style, that occupy the majority of their pages. While the words and images are linked by their exclusive use of black on open white backgrounds, the effect is division, with the center margin separating the two halves of each image-text. The thin, regular shapes of the font also contrast the thicker, irregular lines of the sketches that evoke their moments of creation by Shapton’s living hand. The words evoke only the impersonal process of book manufacturing.

The contrast is especially pronounced since Shapton presents the words of the cover and preceding Prelude in her own handwriting, a style that emphasizes the same, intentionally uneven line qualities as her drawings. The cover art consists only of the looping letters of her title with no other illustration, further emphasizing the drawn quality of the words — reminiscent of Henri Matisse’s own over-sized handwritten words in his 1947 painting, Jazz. Shapton’s Prelude pages also include words and images on both left and right pages, further preparing her contrasting couplets.

In nearly every case, a lefthand sentence names a character who the accompanying drawing appears to depict. Shapton writes, “Jason’s ex-girlfriend was Taylor”, and so the drawing of a woman on the facing page appears to be Taylor. This is deceptively simple. Gender assumptions prevent the image from representing Jason, but Shapton sometimes includes two female referents: “Martin had never mentioned his hauntingly beautiful ex-girlfriend Carwai to Heidi.” The sketch of a woman’s head fills the next page. She appears to be Carwai, not Hedi, in part because her minimally drawn face could be described as “beautiful” — though those features are “hauntingly beautiful” only as a result of the juxtaposed words. The image might as easily be Heidi. But when Shapton writes, “… Mimi found out that it was Evan’s ex-girlfriend Cindy who tried to strangle her in the schoolyard when she was eight,” the facing image of a child appears to be Mimi, not Cindy the ex. This is likely because the child’s eyes are downcast and her hands pocketed, the posture of a victim, not a bully. But again the link is inherently ambiguous.

Roughly a fifth of the drawings depict objects belonging to an ex. Katya’s ex-boyfriend’s postcards appear on both pages, as does Lucy, the only figure to span a two-page spread. Fiona doesn’t appear at all, only her hand-drawn name, because its sound triggers an 11-minute silence over dinner. While Shapton’s characters usually change with each page turn, 17 of her micro-chapters extend for two or three couplets, two for four, and the penultimate for eight. Josephine’s three-couplet dream that her boyfriend’s ex keeps trying to give him “articles of used clothing” also disturbs the formal symmetry, with an article appearing on the second left page and the third remaining entirely blank. Graham’s second and third lefthand pages are blank too, apparently a result of his giving “a number of girlfriends” the same romantic CD compilation. Instead of focusing on exes, Elizabeth’s worry about the women who replace her divides her multi-page sentence into the book’s only fragments.

Margaret’s 16-page sequence serves as finalé, a sub-list of Scott’s exes from a box of journals that Margaret finds and reads. As an unexpected result, Margaret experiences not just guilt but also love for Scott “because everything she adored about him was evident” in his past relationships. The final spread, however, literally reverses this positive realization by placing Margaret’s final words on the right: “This did not go far to alleviate her nausea, or slow the spool of images rushing through her head.” But in fact it has: the opposite left page is now blank. The relief is momentary though. The final couplet returns to form, detailing the rash and stomach pain Louise suffers at the sight of Greg’s ex.

Although each triplet of characters is independent, the accumulative effect is still narrative, with all of the girlfriends, boyfriends, and ex-girlfriends forming three conglomerate characters, whose details vary but not their core experiences. Shapton quotes Kierkegaard in her Prelude: “The chain is very flexible, soft as silk, yields to the most powerful strain, and cannot be torn apart.” Kierkegaard is alluding to Norse mythology, but Shapton implies the impossible-to-break links between exes, as well as the far wider links between all of the characters suffering these same anxieties.

Existentialism aside, Shapton’s characters also share basic features, literally through her unifying gestural style, but also ethnically, sexually, and socioeconomically. Makeda and Olivia are the only African American faces, and Ghislaine and Sophie the only non-heterosexual couple. But privilege is nearly ubiquitous. In addition to educations involving “Med school” and “PhDs”, characters travel between cities for business and continents for pleasure. Character-defining descriptions include: “daughter of two prominent psychoanalysts”, “heiress”, “critically acclaimed” singer, “fashion designer”, “chief designer of a centuries-old fashion house”, “fine-art photographer”, “child prodigy”, “theater director”, and “Argentinian supermodel and the face of a multinational cosmetics conglomerate.” There is also a “nurse” and “salesperson”, but wealth is far more common and overt: Edie “enjoyed Brahams” but “preferred money”, and “Lena’s ex-boyfriend made less money than her other boyfriends. She loved him the best, but he always felt he had something to prove.”

While Was She Pretty? may suggest that anxieties over exes are universal, it also subtlety critiques its circle of privileged sufferers: well-off, good-looking people with an abundance of romantic relationships. These are problems worth having.