The popular narrative is that Alan Crosland’s 1927 film The Jazz Singer, the first talking feature, was the beginning of the end of cinema’s silent era. By the early 1930s, sound synchronisation had ushered in talking pictures, and along with it silent cinema’s end.

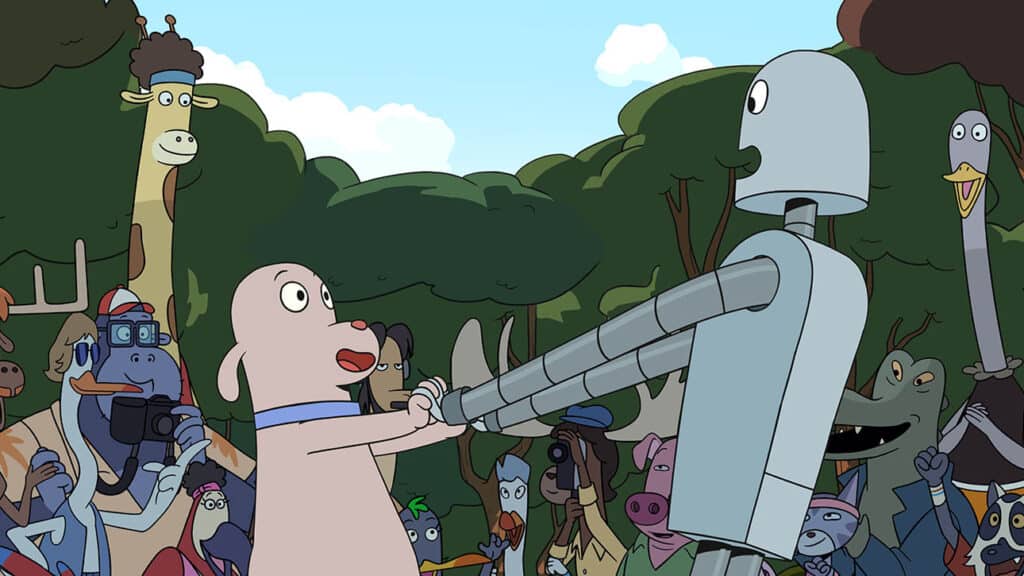

Nearly a century later, Spanish director Pablo Berger’s animation debut, an adaptation of Sara Varon’s 2007 wordless graphic novel, is a modern-day tour de force of silent film. The 2D animation honours the Ligne Claire style of the source material, first developed by the Belgian cartoonist George Remi, aka Hergé, author of the heroic reporter and adventurer Tintin. In Robot Dreams’ production notes, Berger describes this style as “characterised by a narrative way of representing reality using continuous clean lines, flat colours and limited shadows.” Its clean aesthetic is removed from our preconception of early black-and-white silent films.

Robot Dreams is a recrimination of the popular narrative that conveniently ignores how cinema continues to utilise silent film techniques. A prominent example is how actors rely on silence when expressing themselves through non-verbal communication.

“Film is written with images, not with words,” says Pablo Berger in our remote interview ahead of the film’s UK release. The audience knows what Robot Dreams’ characters are thinking, feeling, and communicating with one another without a word being spoken. Berger’s film is a work of wonder, suffused with emotion and charm. The animated frame is filled with creative and humorous details, while the rich sound design and use of Earth, Wind and Fire’s 1978 song, “September” as a melancholic recurring theme, reduces the need for verbiage to an afterthought.

Robot Dream‘s story revolves around Dog Varon, who lives alone in an apartment in Manhattan’s East Village. He plays video games, eats unhealthy food, and longs for the companionship his neighbours have. When he sees a late-night advertisement on television for a companion robot, his eyes widen, and he orders one. Their friendship blossoms, and the pair become inseparable, that is, until Dog is forced to abandon Robot at the beach.

Robot Dreams has a universal appeal because, from a young age, everyone has experienced loneliness and the painful longing for connection, even if we were too young to communicate it verbally. The animal kingdom’s relocation to New York in the ’80s and its unusual harmony of living and working side by side, from a cat and chicken renting a neighbouring apartment to a crocodile running a scrapyard, will inevitably amuse the youngsters in the audience. Meanwhile, the themes of loss and sadness, connection, and loneliness, which will not be lost on the young, will resonate with adults.

There’s a comparison to be drawn with Martin Brest’s 1992 drama, The Scent of a Woman, and Tim Burton’s 2001 fantasy drama, Big Fish. The point is that a film can grow up with us but resonate differently later in life than it did when we were younger. This is true for Lieutenant Colonel Frank Slade (Al Pacino), whose struggles with depression and regret in The Scent of a Woman likely take a backseat to the drama of its young protagonist, Charlie Sims (Chris O’Donnell), for a younger audience yet to experience the weight of regret.

Meanwhile, Big Fish, the story of a man’s relationship with his father, resonates differently depending on age and personal circumstances. Whether this maturation is as dramatic for Robot Dreams, it’s still a film that grows up with its audience, morphing with the individual’s experiences of elation and disappointment.

Robot Dream’s success hinges on the opening scene. Dog plays a video game, channel hops, microwaves a ready meal, and longs for the companionship his neighbouring couple has. The graphic novel begins with Dog receiving the package, but Berger recognises it’s necessary to connect the audience first with Dog’s loneliness and desire for connection. If this is not communicated, then Robot Dreams’ iteration as a film cannot function without first establishing Dog’s life before and after Robot’s arrival. Its inclusion compels a fear of loss but emphasises whether they find one another again; Robot has given Dog a precious gift.

Robot Dreams’ story juxtaposes innocence with the crueller world. This will be more obvious to the adult audience, as in the scene when Dog’s application request to access the closed beach to rescue Robot is denied. In Berger’s ’80s New York setting – the director’s love letter to the city where he lived for a decade while he became a filmmaker – bureaucracy is an unsympathetic antagonist. Dog represents the struggle of the little person against the system. This is not the utopic innocence of something like Gordon Murray’s 1967 British children’s stop-motion animation series Trumpton, which has it in abundance.

It often occurs to me that pure innocence can only exist as imagination and creativity; even then, it’s a struggle. Robot Dreams doesn’t try to capture this same innocent utopia, but there are moments when this spiritual vibe is present. Berger and Varon’s New York needs a layer or undercurrent of darkness.

The craving and affection for pure innocence provoke an unsettling fear in the viewer for these beautiful and sensitive characters. Berger’s ability to make the audience yearn to protect Dog and Robot is deeply appreciated.

Indeed, Robot Dreams is blessed with an emotional intelligence that acknowledges the difference between what someone wants and needs. A conflict gradually emerges between what the audience wants and the characters’ needs, where the characters want something different. This risks viewer disappointment. Berger pitches an effective curveball by thematically embracing how relationships, including friendships, aren’t always for life. Robot Dreams is about appreciating relationships and connections in the moment or for however long they last.

This may sound like a cold interpretation, and in some ways, it is, but Dog and Robot’s friendship is transcendental, which softens disappointment. Robot Dreams asks its audience to let go of the fear they project onto the characters and to see the story we’ve been emotionally immersed in all this time.

Robot Dreams was screened in the Love strand of the 67th BFI London Film Festival and was released theatrically in the UK by Curzon on Friday, 22 March 2024.

![Call for Papers: All Things Reconsidered [MUSIC] May-August 2024](https://www.popmatters.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/all-things-reconsidered-call-music-may-2024-720x380.jpg)