The creators of popular art often have a vexed relationship to the pleasure that their work brings to masses. The public’s appetite for sugary entertainment prompts artists to reshape and reimagine their beloved creations. The dilemma seems particularly intense for cartoonists. Charles Schultz’s Peanuts famously drifted away from Charlie Brown’s subtly subversive melancholy to the eminently marketable antics of Snoopy and Woodstock. Similar things can be said of the anarchical pranks of early Bugs Bunny cartoons and Wonder Woman’s radical feminism.

Anna Haifisch‘s Von Spatz is a strange little ode to the joys and terrors of this paradox. Taking a fictionalized Walt Disney as its ostensible subject, Haifisch’s slim graphic novella follows a fantasized version of Walt Disney (illustrated as a tall, mustachoed cartoon-bird) as he suffers a creative meltdown and seeks rejuvenation at Von Spatz, a rehabilitation center where he, along with cartoonists Saul Steinberg and Tomi Ungerer, creates art free of the demands of the mass market.

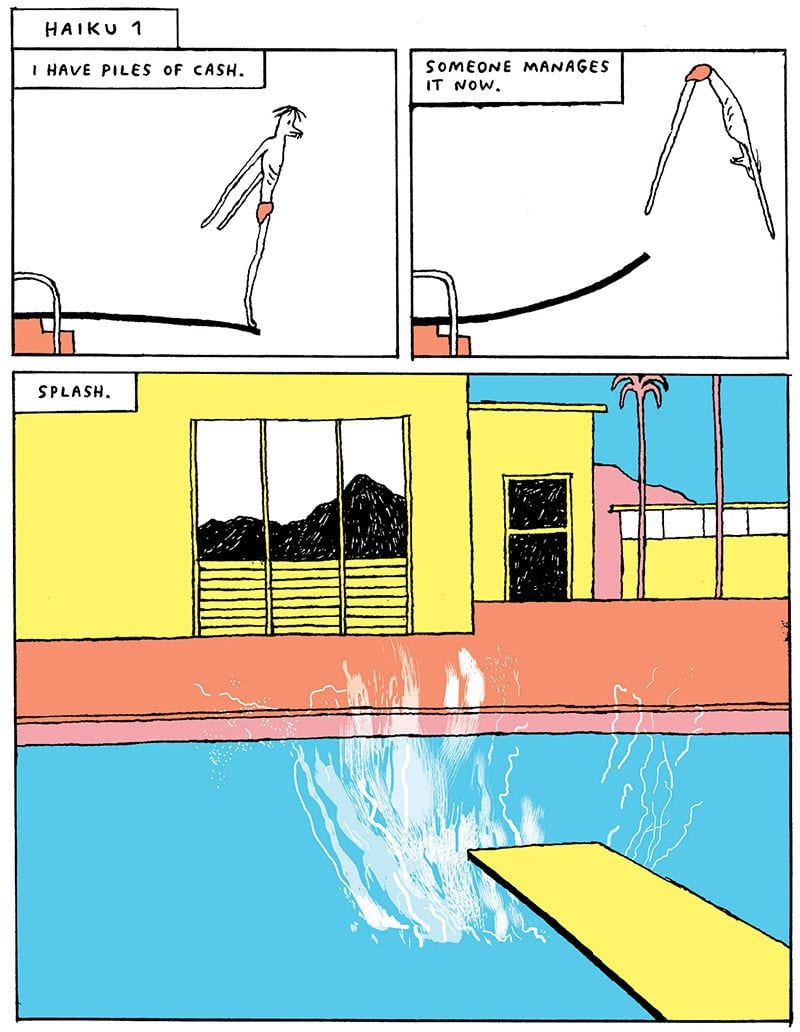

As odd as this synopsis may sound, it hardly captures the idiosyncrasies of Haifisch’s book. Von Spatz (which translates to “From Sparrow” in German) is a sort of cross between Roger Rabbit’s “Toon Town” and Borges’ “Library of Babel”. Here, cartoonists can explore their creative impulses free of the outside world while indulging in a decidedly “cartoony” therapy regimen. Their treatment revolves around the appropriately cartoonish activities of consuming hot dogs and feeding penguins. Within her whimsical counterfactual history, Von Spatz has saved everyone from Osamu Tezuka to Charles Schultz to Wile e. Coyote. For Haifisch, Von Spatz functions as a utopian space through which Haifisch poses a series of riddles about the creative process. In one such sequence, Haifisch pairs a visual reference to David Hockney’s A Bigger Splash (1967) with a poem about Disney’s conflicted sense of self as an artist:

I have piles of cash

Someone manages it now

Splash.

Disney’s literal submersion in Hockney’s painting prompts ambivalence about his commercial victories. Were Disney’s cartoons works of genius on par with Hockney’s modernist art? If so, were they overlooked because of their commercial popularity? Or do accommodations to public demand lead to bland, ineffectual art? Haifisch leaves us to ponder.

Von Spatz is at its best when Haifisch turns to the minutia of the creative process, focusing on her characters’ subtle gestures as they saunter along, mulling over their next cartoon. For example, the sequence “Walt’s Comic” offers a simple pantomime in which Walt gazes at various subjects for his comics and then seems to recoil at their realization on the page. We follow his apparent shock at spying a hairless cat to the tentative pauses that follow as he looks for other subjects, finally surrendering himself to the banal task of making photocopies. Delivered with a perfect deadpan, it all makes for a dry lampoon on the vagaries of the artistic process.

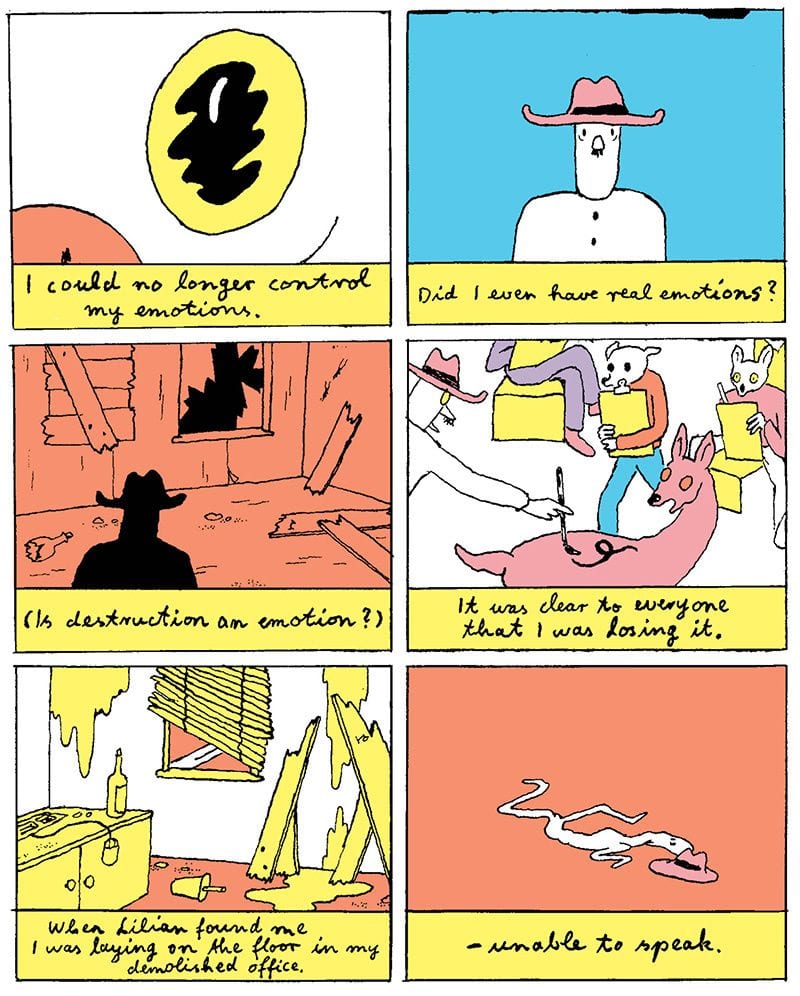

Haifisch’s fantastical version of Walt Disney is at once the most intriguing and the most frustrating element of Von Spatz. In many ways, her character “Walt” is less like any historical version of Disney than an attempt to embody the conflict between popularity and artistic integrity. Her image of Disney is that of a sensitive, timid artist thrust into the pressures of factory style production. His hallucinations suggest that his consciousness has merged with his imaginary cartoon world. An animated penguin transmogrifies into Gumby and Pokey; he laments the toll that his own perfectionism takes on his animators even as he stabs Bambi with a paintbrush; at his low point, his creative soul lies limp like a deflated balloon animal. While we might hope and speculate that Disney harbored such deep conflicts about artistic principle, it seems rather implausible.

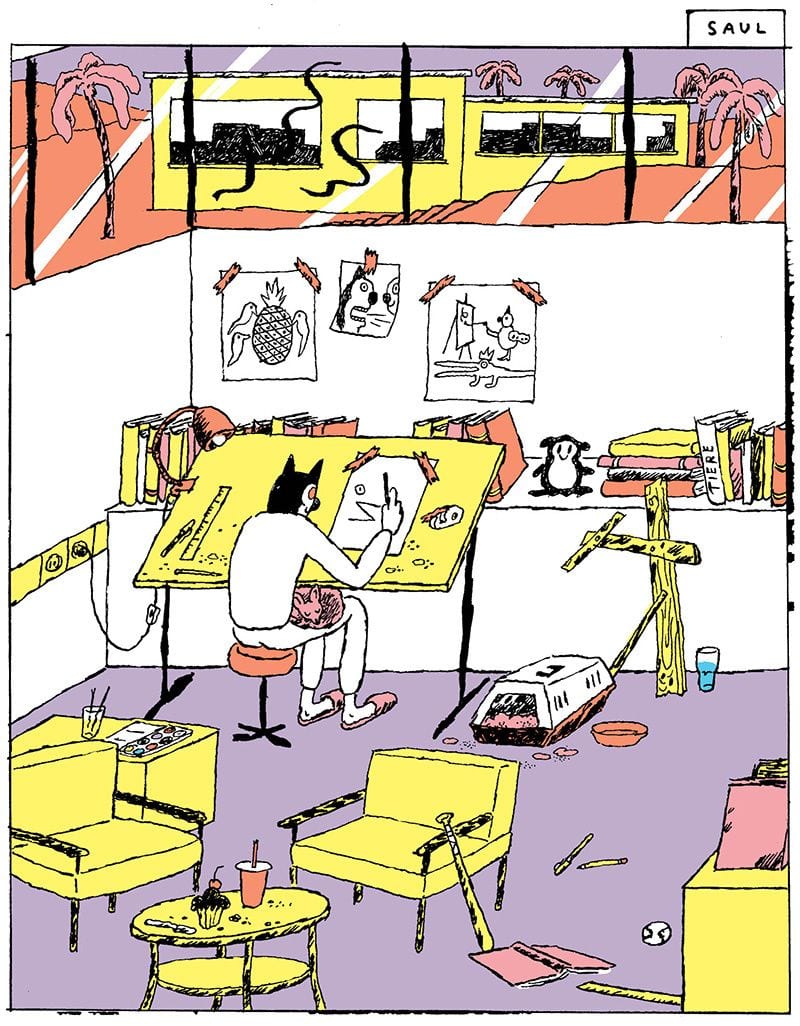

If Haifisch’s picture of Disney feels unsatisfying, she makes up for it with her depictions of Steinberg and Ungerer, who represent potential counter-arguments to Disney’s factory-farmed animation. In real life, Steinberg and Ungerer incorporated the aesthetic of comics and cartoons into high art, fusing the juvenile pleasures of mass culture into art forms that seem intellectually sustainable, able to move forward. In Von Spatz, they are at ease with their artistic process. Where Haifisch’s Disney seems overtaken by public expectations, her Steinberg and Ungerer gaze at their work—and the surrounding world—with uncomplicated appreciation. We see this in her illustration of Steinberg’s studio in which he sits contentedly in his bedroom slippers, churning out visual experiments with a sleeping cat as his audience. While cartooning may be hard work for Steinberg and Ungerer, their ability to maintain ownership of their creations suggest healthier, more harmonious relationship to them.

It’s ultimately this artistic harmony that Haifisch looks to explore even above her characters or plot. Indeed, the book is, in the end, more like an extended thinkpiece on the artistic process than a story per se. The self-referentiality and general oddness of Von Spatz seems fitting. It embodies the attachment to enjoying one’s own creative process that Haifisch subtly explores throughout. The obscurity of it all may be a turn-off for some, but it will reward readers, willing to follow Haifisch’s peculiar sensibilities.

![Call for Papers: All Things Reconsidered [MUSIC] May-August 2024](https://www.popmatters.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/all-things-reconsidered-call-music-may-2024-720x380.jpg)