“War is like love; it always finds a way.”

— Bertolt Brecht, Mother Courage and Her Children

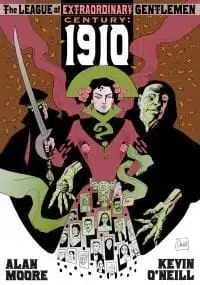

Alan Moore’s work, like all stories, has always been about humanity and politics, struggling with concurrent truths and hoping to find an answer that will lead to a better, stronger, happier world. If V for Vendetta echoed Moore’s sentiments about Margaret Thatcher’s, if you’ll excuse the “timely” pun, “dark reign” over England, and Lost Girls dealt with modern-day sexual repression via an examination of pre-WWI Europe and classic children’s literature, then his latest opus, League of Extraordinary Gentlemen – Century: 1910 is about the world’s current state of constant, intractable war, a seemingly timeless and unending series of conflicts between the Christian nations of the West and the Islamic nations of the East.

The Spanish Inquisition, The Crusades, the initial Gulf War, and the alleged “War on Terror” are all individual conflicts that are part of a larger, centuries-long war between Western Christianity and Eastern Islam, and they all inform the story, characters, worlds and lessons of 1910. Twelve years have passed since the Martian invasion threatened to destroy the Earth, and it is decades still before the 1960s League will visit the Blazing World, and over 90 years before hijacked airplanes ram into the World Trade Center, the Pentagon, and Shanksville, Pennsylvania, killing thousands in what will feel like the blink of an eye. But while Bertolt Brecht’s Threepenny Opera, the classic musical Moore is appropriating as his storytelling backdrop (much as he did with Edgar Allan Poe’s Murders in the Rue Morgue in the first series, and H.G. Well’s The War of the Worlds in the second) takes place in 1910, it serves as a potent, chilling and visceral reminder that while both religions talk about a world without end, the confrontation between East and West has, so far, only produced a war without end, and both sides seem perfectly okay with that.

Mina Murray, Alan Quatermain “Junior” and Orlando are the backbone of this incarnation of the League of Extraordinary Gentlemen, and if they were a band, E.W. Hornung’s A.J. Raffles and William Hope Hodgson’s Thomas Cranacki would be their back-up singers. Also briefly present is Captain Nemo, the famed literary Sikh pirate, whose daughter, Janni, abandons him on his deathbed for London. As with some of Moore’s most hailed characters, however – from Rorschach to V to Promethea – Janni, alias Brecht’s “Jenny Diver”, cannot outrun her destiny to take her father’s place as the world’s foremost dreaded science pirate, beautifully illustrated in metaphor by Kevin O’Neill as she escapes her father and dives into the sea, searching out a new life.

Moore’s brilliant substitution of Sikhism for Islam serves several outstanding purposes. For starters, it illustrates the ignorance of the more trigger-happy portions of the West who are quick to blame anyone who looks vaguely Arabic for all that is wrong with modern society. It points out the foibles of ignorance, racism, impatience and poor international cultural education that pervade the West. What’s more, by making his “terrorists” Sikhs instead of Muslims, he points out to the entire reading Western world that terrorism is not a tenant of any religion, but rather a very flawed ideological viewpoint of humanity. It can be argued that MacHeath, the “Mack the Knife” of Brecht’s musical, is more of a terrorist than Nemo or Janni could ever turn out to be; MacHeath, so it goes, is the infamous serial killer Jack the Ripper, who kept London’s Whitechapel District in a constant state of terror for months in 1888 (interestingly, the story of the Ripper was the subject of another earlier Moore work, From Hell, which is based on actual research on the subject, and not famous literature as the League series is). One could say Janni’s rage, provoked by rape, mistreatment, abuse and other horrible misdeeds during her stay in London, are completely justified, so when MacHeath is let loose from the gallows by orders from on high at the end of the tale, the sinking feeling in the reader’s gut shows who the true terrorist is. Surely, MacHeath will kill again, and Moore even illustrates how his reign of terror may affect the future.

Using the time-traveling character Andrew Norton (created by author Iain Sinclair), the so-called “Prisoner of London”, Moore is able to obliquely hint at many real-world events, such as the September 11th attacks in the United States, and the 7/7 London bombings. A thread beginning in this book, detailing W. Somerset Maugham’s Crowley-esque Oliver Haddo and his obsession with the creation of a potential Antichrist who could end all life on Earth, even links the modern day (the setting of the final book in the Century trilogy) to the end of the world. Terrorism, it would seem, has escalated over the centuries from serial killing to hijacking airplanes to the magicks of a crazed cult threatening Armageddon.

No more is this evident than in the final sequence, as MacHeath and his comrades dance around the ruins of a Nautilus-ravaged London to the tune of a reworked version of “What Keeps Mankind Alive”. MacHeath makes his worldview almost appetizing and sympathetic, and it’s easy to see how youth like John Walker Lindh will eventually subscribe to a latter-day version of this way of thinking. As MacHeath explains, “What keeps mankind alive’s the millions yearly that we mistreat and cheat;/The beaten, burned and barbecued./Mankind may just survive if it sincerely/Keeps every decent human urge subdued./Try not to trim the truth to suit your needs: Mankind is kept alive/By monstrous deeds!”

It’s too bad shrapnel or wreckage didn’t crush the newly-freed MacHeath. It might have saved us the last decades’ worth of horror.