There’s nothing simple about penning a story in Iran. And few things more complicated than writing a story about love. Let’s put those two together, shall we?

Shahriar Mandanipour, in his first major work to be translated into English, tells a story of love, secrecy, jealousy, and political danger while simultaneously walking the reader through the difficulties of obtaining a publishing permit in Iran. If a story even hints of sexuality or improper behavior, it has little to no chance of reaching the reading public without severe alteration.

But these days, with all my being, as a will and last testament, I want to write a bright love story in which there is no sorrow, no one dies, no hearts suffer, not even the tip of a pencil breaks.

It actually turns out that hints are worse than flagrant descriptions; the human imagination has more power to cross the boundaries into restricted territory than the pen. And euphemisms abound, so that a poem about ripe fruit or a flowering plant becomes quite graphic in classically styled Iranian literature. Mandanipour’s narrator strives throughout to educate the reader about Iranian culture and literature, as well as to tell the story of two young lovers. A few chapters in, he remarks, “for you to fully discern the symbols and metaphors of my story, I am forced to introduce you to yet another form of censorship — socio-cultural censorship — which in Iran has a history of more than 2,000 years.”

To the authorities within the novel, Iranian authors in general have a grave responsibility to the people who may encounter their stories; “He must not allow immoral and corruptive words and phrases to appear before the eyes of simple and innocent people, especially the youth, and pollute their pure minds.” To the narrator of Mandanipour’s story, represented as though he is the author himself, this is a betrayal of the complexities of the human experience.

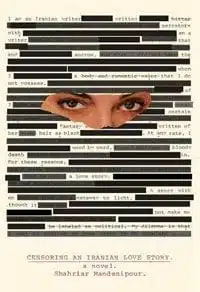

Dara and Sara, two young people in modern Tehran, form a connection through a shared love of banned (and therefore fascinating) literature. Using code and their wits to find ways to communicate when society prohibits their interaction, Dara and Sara take increasingly greater risks in their attempts to know one another. Mandanipour uses the clever gimmick of striking out controversial words, sentences, even paragraphs, so that the reader has to not only read between the lines to decipher the true meaning of conversations and descriptions, he must read behind the lines, as it were. One imagines the censor’s pen laboriously marking up the most interesting parts of the story.

Mandanipour has also used a bold font to emphasize particularly cinematic passages and conversations, and refers frequently to famous scenes in movies that may be sold on the black market, films deemed too morally damaging or scandalous to allow the people to have access to.

It’s not only the present political realities that authors and artists must take into consideration. The narrator comments:

… we Iranians, having lived under the dictatorial rule of kings for 2,500 years, have expertly learned that we should never leave any records or documents behind. We are forever fearful that the future will bear even harsher political circumstances, and hence we must be extremely vigilant about our lives and the footprints that linger in our wake.

Through the progression of Mandipour’s novel the reader observes the narrator making, reversing, and re-imagining authorial decisions. The writer starts out in control, directing the action with precision, but as the story progresses, gradually the ability to control events and emotions is lost. Dara starts to act irrationally, spurred on by his jealousy in seeing Sara in the company of other men, as his poor background makes him an unsuitable suitor. The ‘author’ attempts to bring Dara back under control, but realizes he cannot.

Mandanipour masterfully describes the chaos of a relationship gone off the rails, emphasizing the unpredictability of the actions of a lover who believes himself scorned. Relationships are tough in any setting; when every action is observed by the neighbors and potentially reported to the authorities, they become downright frightening.

Mandanipour wrote Censoring an Iranian Love Story while holding an International Writers Project fellowship residency at Brown University, and is now a visiting scholar at Harvard University. Contemporary fiction with roots in authentic Iranian culture these days is hard to come by, and Mandanipour does an excellent job of representing the artists of his country. With sly tongue-in-cheek wit interspersed between moments where the narrator despairs of ever getting this story past the censors, Mandanipour manages to represent the difficulties of publishing anything based in contemporary human experience in Iran, as well as tell a twisted love story.