Cast your whole vote, not a strip of paper merely, but your whole influence.

–Henry David Thoreau, “Civil Disobedience”

I realized now that my previous attitudes had been badly mistaken.

–Daniel Ellsberg

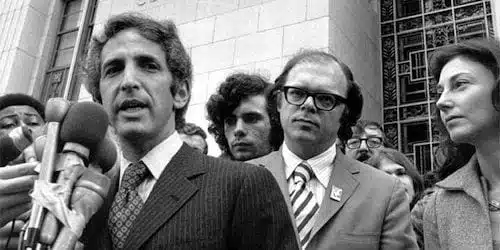

“I think it is time in this country to quit making national heroes out of those who steal secrets and publish them in the newspaper.” In June 1971, Richard Nixon learned Daniel Ellsberg had leaked the “Pentagon Papers” to the New York Times. At the time, he was distracted; his daughter Tricia had been married the day before and besides, the published portion concerned history, Kennedy and Johnson’s mistakes. Henry Kissinger saw a greater issue at stake: “It is an attack on the whole integrity of government if whole file cabinets can be stolen and then made available to the press,” he said. “You can’t have orderly government anymore.”

Kissinger’s assessment is stunning on multiple levels, not least being the pretense that the Nixon Administration constituted any sort of “orderly government.” This disparity — between performance and reality, or perhaps more accurately, between fundamentally different types of performances — lies at the heart of The Most Dangerous Man in America: Daniel Ellsberg and the Pentagon Papers. As the documentary traces Ellsberg’s decision to release the report — completed by the Rand Corporation, where he worked during the 1960s — it also raises questions concerning government and citizens’ responsibilities and rights.

Ellsberg serves here as a representative of both, a onetime dedicated administration official who becomes something of a model whistleblower, his experience “inside” helping him to anticipate his opponents’ responses. “He came from an enormously powerful war bureaucratic machine,” observes Janaki Tschannerl, a peace activist who worked with Ellsberg, “And so his thinking came from the entrails of that machine.”

The evolution of Ellsberg’s thinking is a story in itself. Even as Attorney General John Mitchell was granted a restraining order against the Times‘ further publication of the papers, Ellsberg took a next step, releasing the papers to Washington Post, the Boston Globe and Chicago Sun-Times, and so on, until they were in the hands of 17 different news organizations, as well as Alaska’s Mike Gravel, who read the report into the Senate record.

The effects of the papers’ release were both immediate and long-term. Indeed, according to, the effects resonate to this day. For one thing, the Supreme Court decision regarding the injunctions (they were unconstitutional prior restraint) set precedent for use of the First Amendment going forward. Or another, the content was certainly explosive, as the report tracked deceptions concerning the Vietnam war over multiple administrations. This has been Ellsberg’s focus in interviews then and now, that the government cannot be trusted to tell the truth or even to be consistently invested in the United States’ best interests, which means that citizens must be vigilant, and hold their representatives in all three branches accountable for their decisions and actions.

The documentary makes this case emphatically and dramatically. It also makes the case inventively, using close-up green-tinged reenactments of the Xeroxing (which took months), cartoon illustrations of secret meetings and late-night encounters with police, and generic archival footage (of troop activities or antiwar protests) to denote other specific memories for which there is no conventional visual evidence. These images, along with documents and talking heads, as well as audiotapes of Johnson and Nixon in the White House, reflect the film’s mix of narratives, personal and political, broad and detailed, in order to convey the way Ellsberg’s own transformation signifies — in various ways — historical shifts.

To make this point, Ellsberg recounts a car accident that killed his mother and sister, when his father was driving. Contemplating that incident (the boy Ellsberg was in the car too), he says, “I think it did probably leave an impression on me, that someone you loved and respected could fall sleep at the wheel and they needed to be watched.” This question is turned the other way in Ellsberg’s relationship with second wife Patricia, traced here in a way that suggests he was also one who “needed to be watched.”

When she first met Dan, Patricia recalls, she was warned, “He’s brilliant but dangerous, meaning that he was quite a ladies’ man.” At least for a time, their romance was premised on acknowledging but not focusing on their different views of the war: she was against it and he was helping to make it — even despite his protestations that while working under Robert McNamara at Defense and at the Rand Corporation in Santa Monica, he was arguing against escalation. Still, he says, looking back, he was seeing the war then “in the context of a worldwide conflict with Communism. We were protecting democracy, or at least the idea of democracy.”

As this idea was increasingly untenable, so was Ellsberg’s relationship with Patricia. They called off their engagement, when she made clear her disappointment that he was supporting and even helping to wage the war: “He was more part of this than he thought,” she says, over generic archival footage of a Vietnamese nightclub singer. The film cuts in here Ellsberg’s own nostalgia about his days as a marine (“I loved being a company commander”), thus constructing an emotional narrative to explain his and his nation’s histories, a mash-up of romance and machismo, projection and desire. As Patricia remembers that he was “still buying into the whole zeitgeist of that war,” he explains their breakup as a function of her essential lack of faith. “How can I be married to somebody,” he says, “who doesn’t give me the benefit of the doubt on this somehow?”

At this point his own doubts begin to intervene. Assigned to formulate “pacification” policy — which, he notes now, in an interview with Paul Jay, is comparable to “counterinsurgency” — Ellsberg went on his own fact-finding journey Vietnam. His experience, on patrols and in discussions with officers, changed Ellsberg’s position form that of what Tm Oliphant calls “true believer” to skeptic. “I was beginning to realize we couldn’t beat this enemy in their own back yard,” he recalls, “These guys were not going to give up.” At the same time, he was becoming aware of the extent to which U.S. policy-makers, himself included, were lying outright to the American public. When the 1968 Tet Offensive shook that public’s “faith in the war,” Ellsberg says, he began to seek ways to stop it.

Ready at the time to go to prison for his action, Ellsberg also believed, he says now, “If the American people knew the truth about how they had been lied to,” they would respond appropriately. However, his hopes were soon dashed: even after learning the truth, American voters “proceeded t ignore it,” reelecting Nixon in a landslide. The president’s own paranoia and corruption are soon exposed, in large part in his reaction to Ellsberg, namely, the Watergate break-in and the Plumbers Unit, led by Bud Krogh. “At no time did anyone ask if this was the right thing to do,” Krogh recalls here.

As the film shows, Ellsberg has repeatedly asked this question. Coming to it late, he has felt guilt and responsibility. And since 1971, he has urged others to follow his example and forge their own. The comprehension of his own power to effect change was crucial, he says. Hearing the declarations of other young men who were willing to go to prison in order to protest the war, he was moved to action. “It was as if an axe had split my head,” he says now, sitting with war protestor and social justice activist Randy Kehler. “What had really happened was that my life had split in two, and it was my life after those words that I have lived every since.” The Most Dangerous Man in America recounts that trauma, and makes clear its ongoing relevance.