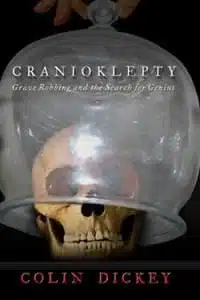

Cranioklepty is a new word for a pastime that has fallen from fashion. Colin Dickey’s book is about the practice of stealing skulls from the graves of the renowned, in order to possess the site of their genius. The eminence of these victims of post-mortem theft is important, because the events that Dickey recounts took place during the Enlightenment, when great knowledge was very much in vogue. So these acts of grave robbery were motivated by a combination of burgeoning interest in the idea of genius and a longstanding passion for relic hunting.

Two of the four main examples included in this book are composers: Haydn and Beethoven. The others are the Christian philosopher Emanuel Swedenborg, and the 17th century English writer Sir Thomas Browne.

Haydn’s is the most compelling story. This is in part due to the fact that the man who stole Haydn’s head after his death had been a friend of the composer’s when he was alive, which adds a pleasing personal dimension. Carl Joseph Rosenbaum worked as an accountant for the Esterhazy family, the extraordinarily wealthy nobles who were Haydn’s patrons. He appears to have been a comprehensive diarist, and recorded in detail the preparation, execution, and aftermath of his grave robbery — another reason why the Haydn story is the most interesting tale of cranioklepty.

Rosenbaum had apparently been plotting to take the composer’s head for some time before Haydn’s death. He was no stranger to this activity, having already purloined the head of a noted singer, Elizabeth Roose. His first theft was something of a trial run, however, with the preservation of the skull not being an unmitigated success: having been soaked in limewater for four months it became brittle and began to grow algae. His efforts with Hayden were more successful, and the story of its acquisition is a fascinating one, rich with comic asides about drunken gravediggers and the unfavourable view Rosenbaum’s wife had of his hobby.

Dickey’s source material is not always this comprehensive though, and at times he can only provide anecdotal snippets. However, he generally manages to tie these together, and although he draws some rather vague connections at times, the overarching narrative is well sustained. If the skull is the book’s primary subject, then its backbone is the history of the disciplines of phrenology and craniometry. A fascination with the first of these provided Rosenbaum with the impetus for his skull-stealing. The premise of phrenology was that the personal traits of a person could be determined by the shape of the skull. This gave way to craniometry, which gave greater significance on the skull’s size: a bigger skull could hold a larger brain, and this, insisted craniometrists, was indicative of high intelligence.

Although Haydn’s skull was not reunited with his body until 1954, it had a less turbulent time than some of the others examined by Dickey. Goya’s body remains headless to this day; this mystery is not explored in depth in this book, since there are no clues that might lead to the thief. The unfortunate fate of Beethoven’s head begins even before his burial, with a botched autopsy that resulted in the head having to be held together with clay when it was put on public display prior to the composer’s funeral. Much later, Beethoven was exhumed by interested scientists who wanted to study his skull to support their craniometric claims. During these proceedings, some fragments of bone went missing and did not re-emerge for decades.

Swedenborg’s head was repeatedly stolen, but disputes over the identity of the recovered relic meant that even when there was a skull interred with his skeleton it was uncertain whether it was actually his. Meanwhile, the location of Thomas Browne’s head was always certain; it was for many years in the possession of the Norwich and Norfolk Hospital Museum, where it was the subject of an ongoing feud between this institution and the church in whose grounds the rest of Browne’s remains lay.

A preponderance of headless corpses and eccentric scientists means that Cranioklepty is certainly a macabre book, but the silliness of the pseudo-sciences it debunks makes it more entertaining than unnerving. The skull has always been immensely symbolic and its image continues to occupy a prominent place in art and culture; this book is both an effective commentary on this and a worthy addition to it.