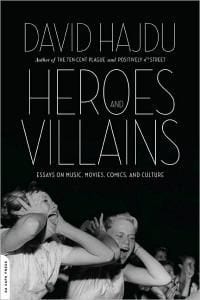

David Hajdu is the music critic for The New Republic and the author of three well received books: Lush Life, (1997) a book about the great jazz composer Billy Strayhorn, Positively 4th Street, (2002) which examines the rise of folk music at the end of the 50s by focusing on the artistic lives, loves, and music of Bob Dylan, Joan Baez, her sister Mimi, and Robert Farina. Hajudu’s most recent book before this essay collection was a study of the rise and fall of comic books called The Ten Cent Plague(2008).

Clearly, Hajdu is on a publishing roll and able to write on a variety of popular culture topics. The essays collected in Heroes and Villains. Essays on Music, Movies, Comics, and Culture come from a wide range of publications: Atlantic Monthly, Los Angles Times Book Review, New York Review of Books and Mother Jones. They show Hajdu as a scholar (he currently teaches journalism at Columbia University) and journalist who is interested in making sense out of the current cacophony in contemporary music and the myriad forces –both personal and technological — that shape the artistic production and public consumption of music. The essay on My Space is a good example of Hadju being able to explain and show how the contemporary phenomena of My Space is actually responsible for a certain conformity of taste and that it is not the great liberator of human musical creativity it is reported or hoped to be.

Hajdu’s 2003 piece simply called “Wynton Marsalis” is a brilliant analysis about Marsalis’ place in jazz history. The essay uses the rise and fall of Marsalis’ standing in popular culture as a metaphor for the rise and decline of jazz in popular culture and tells how his brother Branford represents the progressive/evolutionary side of jazz. Wynton is the classicist, brother Branford the bold brassy new wave jazz creator.

It’s a clever piece of writing and weaves into the text catching a chance performance of Wynton in a small club on a vacant weeknight in August in New York, the sound of a cell phone going off, and then Marsalis’ ability to play each note of the cell phone ring. It’s a clever introduction to what becomes a reflective trenchant meditation on jazz and Wynton Marsalis.

Hajdu’s affectionate recollections of watching Elmer Fudd cartoons on Saturday afternoons is another example of Hajdu’s clear writing style and his ability to write insightful portraits. The Elmer Fudd essay is a smart piece of character analysis. Fudd is “a grown man, old enough to have gone completely bald, Elmer J. Fudd is an oversized newborn, proportionally and psychologically.”

Hajdu’s is also an historian of popular culture. For example, “Billy Eckstine: The Man Who was Too Hot” shows us Hajud’s ability to enter sympathetically into a past era to frame the success and almost stardom of a now mostly forgotten Eckstine. Hajud resurrects Eckstine’s style and singing ability and laments how the sexual mores of the ‘50s and unspoken racism of the time prevented Eckstine from achieving stardom.

This collection also includes essays that critically examine books about famous pop music stars such as Sammy Davis Jr. and John Lennon. In these essays Hajdu is his most critical. His scathing essay on Sting’s medieval inspired CD is amusing in its dressing down of Sting’s preposterous and pretentious singing style and choice of music.

Part of what makes Hajdu such a good music critic and clever pop culture observer is his ability to see beyond the obvious. Here, for example, is Hajdu on Sammy Davis Jr. “We don’t remember Davis for who he was or what he did when he mattered most as much as for the wicked joke he let himself become.”

Hajdu has a keen sense of the social significance of pop culture artists and he shows how they often reflect and create the social climate of the day.

Hajdu’s deep appreciation and knowledge of music, especially jazz, however, does not prevent him from administering ‘tough love’.

In “The Great Men of Jazz”, Hajdu chastises Ken Burns’ CD and text for ignoring huge swaths of Jazz history. He admonishes Philip Norman’s book John Lennon: The Life for his ham-fisted treatment of Lennon’s lyrics and his “repetitious… bloodless prose.”

Throughout, Hajdu writes in a clear, straightforward style and possesses a sympathetic feel for the lives and music of pop music performers, and this in turn allows him to get past the surface of their lives. Anita O’Day and Bobby Darrin, for example, reshaped themselves and used their talent to climb onward and upward to the top of their musical fields, he writes. The result, however, as in Bobby Darrin’s case, was tragic; he lost his way or identity by recalibrating his musical identity over and over again to try and maintain popular culture success. O ‘Day’s personal life turned out to be a disaster.

Hajdu’s literary voice is thoughtful, urbane, and cosmopolitan in a very New York City sort of way. His pop culture gaze seldom looks beyond the US except for the essays on the two former Beatles, Paul McCartney and John Lennon, and his tribute essay to the French-Italian jazz pianist Michel Petrucciani; the latter mainly because he both succeeded and ended his career in New York.

Jazz, as Hajdu recognizes, is no longer America’s music but has become a world musical form absorbing the sounds and flavors from diverse cultures from around the globe. Alas, I wish some of the essays reflected this reality. This is not so much a flaw as a question of focus.