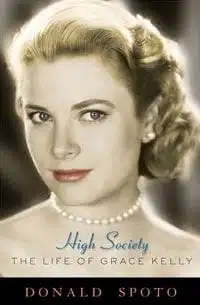

The art of the biographer is to drag the statue off its pedestal. A good biographer brings the famous, the exalted, or the notorious down to our level and makes them human. In High Society: The Life of Grace Kelly , Donald Spoto tries desperately to do the opposite. He is so busy pushing Grace Kelly up on the pedestal that he never lets us see her up close. He insists on keeping her far away, insisting on her superior excellence and forcing us to gaze at her from afar.

This is a shame because Grace Kelly lived a fascinating life. This book was a fine opportunity for Spoto to introduce Kelly and her work and her journey from the Philadelphia suburbs to acting prowess to the height of Hollywood stardom and onto marriage and life as a real life European princess. It is a story that begs to be told. Kelly was, by all accounts, a dazzling beauty, a woman who combined those good looks with a genuine gift for acting and a stubborn independent streak to become an Academy Award winner. She stared down the old studio system, fighting to do the movies she wanted and on her schedule. Then at the very peak of her fame and achievement she left it all for the Prince of Monaco, in reality, a king. She was at the center of the first “wedding of the century” with all the attendant attention and then she mostly dropped out of sight for the rest of her life. It is an incredible story. If Grace Kelly had lived in today’s media saturated environment, she would have created a huge TV, internet, celebrity frenzy. She would have been Princess Di plus Jennifer Aniston. Yet today most people, especially the young, have barely heard of her. A nicely done biography would go a long way to sole that problem.

Spoto has not written that book. He has not written a good biography but something closer to hagiography. He strongly wants to convince us of something that is obvious: that Grace Kelly was a woman of unusual grace and beauty and had an exceptional and strong personality. Spoto spends much time trying to polish a gem that shines all on its own. He tells us that Grace was a virgin in high school, had excellent diction, impeccable manners, was “ethereal without being unrealistic”, her acting and voice were “poignant without sounding arch”. She was ahead of her time in fighting racism and accepting homosexuality. She did not have nearly so many affairs as the rumors would have it. She yearned to be a mother and a wife. It is quite an achievement but this book manages to make Grace Kelly’s life seem boring. She does all the right things, makes all the right choices, glides through troubles and triumphs over all.

Even so, the inherent fascination of Kelly and her story does manage to almost rescue Spotos’s book, especially during the last third. As Kelly comes into her own as an actress, her strong will becomes more and more clear. The most fascinating aspect of Kelly’s narrative turns out to be not to be her mesmerizing and graceful appearances in film, nor her fairytale marriage but her sense that she ought to be in control of her own life. Against a father who consistently belittled her success, directors like Hitchcock who sought to mold her as an actress, a studio system that tried to exploit her, and a celebrity culture that expected her to always be available, Kelly was after the power to choose her own path. The marriage to Prince Rainer was not the typical story of a woman swept up in a royal love affair, dazzled by the trappings and allure of a prince. Rather, it was the willful decision of a woman who had always sought control and saw this marriage as her fulfillment and future no matter what the long term cost to her fame or career or celebrity.

That much at least comes through in Spoto’s book. However, not much else of real significance makes it past the author’s adoring treatment. The reader is left to suspect that there is much more to the story and person of Grace Kelly than what Donald Spoto tells us.