Their lives were defined by what they opposed as much as by what they supported; they were connected in only the most general terms, shaped by slavery and imprisoned in the amber of our common assumptions.

Frederick Douglass and Abraham Lincoln have been for generations two of the accessible saints of the American iconography. For black Americans, Douglass has been held high as the defining pre-civil rights era example of speaking truth to power. For Americans generally, Lincoln remains the president most responsible for holding a fractious nation together.

In recent years, Lincoln biographies from Doris Kearns Goodwin, James M. McPherson, and Ronald C. White, among others, have taken the wraps off old depictions of Lincoln, their nuanced investigations revealing fresh layers to the complex, driven, conflicted man who would become the 16th President of the United States. Readers of historical nonfiction haven’t been so lucky with biographies of Douglass, the runaway slave who transformed himself into a publisher, activist, and one of the most commanding orators of the American 19th century.

Douglass biographies have been fewer and farther between, and inevitably marginalized, to some degree, on the lower and distant shelves of the bookstore of the national narrative (with the other black studies books) in a kind of de libris historical segregation. The two figures are connected by slavery, the ”peculiar institution” that would define them both. It makes sense that that institution should unite them literarily.

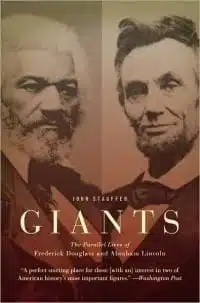

John Stauffer’s Giants brilliantly addresses this absence with an eloquent, muscular, compassionate, thoroughly readable conflation of two singular American lives, a biography of two intersecting lives whose grappling with the evil of slavery created a bond uncommon in American history, and almost as rare in American literature.

Stauffer, chair of the History of American Civilization and an English professor at Harvard, takes the disparate strands of two American stories that couldn’t be more different and shows, organically, what brings them together in an era of defining national turbulence. And Stauffer shows how Douglass and Lincoln were both ambitious test cases for the emergence of celebrity, the drive for publicity, and the cult of personality that would shape both political discourse and popular culture in the decades to come.

After years of shuttling between owners in Baltimore and Maryland’s Eastern Shore, and failing at previous escape attempts that saw him sent back to the bondage he was born into, a prisoner of American war, the unrepentant runaway slave Frederick Augustus Washington Bailey took a train on the B&O Railroad from Baltimore to Wilmington, Delaware, and from there a steamboat to Philadelphia, and another train to New York City, and freedom, arriving on 3 September 1838. He changed his name to Frederick Douglass a few weeks later. ”For the rest of his life he would celebrate September 3 in place of his unknown birthday,” Stauffer writes.

For years Douglass refined this personal story, using it as the springboard to a lifetime of activism on behalf of the abolitionist cause. With the help of the famed abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison (whose anti-slavery journal, “The Liberator”, Douglass would read ”as devoutly as his Bible”), the former slave transformed himself into a spellbinding orator who attracted rapturous audiences in the United States and abroad.

Douglass thus started the process of building his own starmaker machinery; he was recreating himself into what the orator Henry Clay (more about him later) described as a ”self-made man”, an individual animated by his own sense of manifest destiny. Leave it to Stauffer to elaborate, charitably but incisively, on one of this self-made man’s other ingredients:

Her name was Anna Murray and she was a free woman [Douglass was engaged to marry] … It was Anna’s money that purchased Frederick’s train ticket on the B&O … Soon after returning to Baltimore in late 1836, Frederick had boasted that ”with money” he could “easily have managed the matter” of running away. Anna’s money, coupled with her independence as a free woman, made his escape possible.

Yet Frederick totally ignored Anna’s role in helping him escape, both at the time and in his memories of the event. Recognizing it would have cut against his image of the self-made man and representative African American that, even now, in his first days of freedom, he was already beginning to cultivate … He was participating in a tradition of self-made men that went from Ben Franklin and Natty Bumppo through Lincoln on up to Malcolm X — a tradition that dismissed the roles of wives and women in shaping the man’s success. What made Frederick’s situation unique was that he established the tradition of the self-made African American.

The media machine of Frederick Douglass was up and running, its inventor in the company of scholars, publishers, activists, politicians and, eventually, the 16th President of the United States.

Abraham Lincoln took a similar vagabond trajectory into the national consciousness. Born in Kentucky, he and his family moved to southern Indiana when he was seven years old, and from there to Illinois when he was 21. The strong, rawboned Lincoln would come to take trips down the Mississippi River, a liberating form of indentured servitude courtesy of being rented out by his father as a hand on a flatboat to New Orleans for $8 a month.

New Orleans seemed like a foreign country. With a population of 50,000, including 30,000 African Americans, it was a black metropolis to Abraham… New Orleans was the largest slave entrepôt in America, with scores of auction markets where people were bought and sold like horses. It was almost impossible not to be in the city and not experience the sights and sounds of slavery … Abraham reportedly saw blacks chained and mistreated, and ‘his heart bled’ for them … What shocked him, what he identified with, was the plight of others who were forever unfree.

But there were ethical detours Lincoln took en route to his reinvention as a self-made man. Lincoln parlayed jobs in New Salem, Illinois, as postmaster and partner in a general store into the first throes of a political career when he was elected to the state assembly, a loyal member of the Whig party started by the statesman and orator Henry Clay, for years Lincoln’s oratorical and philosophical ideal.

…Lincoln followed a Whig platform and used women’s second-class status as a source of humor. Blacks too were denied suffrage, and Lincoln wanted to keep it that way. In fact, he later chastised Martin Van Buren for embracing black suffrage in New York State.

”On the suffrage issue, Lincoln was being pragmatic. To endorse blacks or women’s rights would have been political suicide.

It’s this almost ruthless pragmatism that Lincoln would use again and again throughout his career — ultimately and most notably as a catalyst for his rationale for the Emancipation Proclamation. For all its lofty rhetoric, the Proclamation was a canny, practical decision that freed the slaves, created a new and eager source of conscripts, sent a shock wave deep into the hoop-skirted South, and sparked concerns of how black soldiers would be treated by the North and South alike — concerns aired by the former Maryland slave who’d come to call on the White House between 1863 and 1865.

Stauffer’s intertwining of Douglass and Lincoln seems like a natural pairing: two like-minded intellectuals with a shared love of poetry and the fables of Aesop, and a mutual distaste of slavery. But where Douglass’ opposition to slavery was a moral absolute steeped in his own experience, Lincoln was subject to an evolving conviction on the issue.

Lincoln grappled not just with moral principles but also with political realities vis-à-vis slavery. In Stauffer’s capable hands, the resulting tug-of-war between the two is a study in the evolution of both a friendship and a political world view.

Whether exploring the quiet marital turmoil of both men; Douglass’ channeling of Lord Byron, the long-dead poet ”who helped Douglass remake himself in appearance, style, voice”; or Abraham’s adoption of the Scottish poet Robert Burns as ”a literary soul mate”, Stauffer achieves that prime objective of the biographer: blending history and scholarship in a narrative that conveys the energy of a good story.

We’re witnesses to Lincoln’s politically expedient morphing from Whig to Republican, even as he held fast of Whig views on slavery. ”He never questioned the validity of the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850, either politically or constitutionally”, Stauffer observes. ”It was a necessary concession to the South …”

By 1861, Diouglass and Lincoln — the leaders of two separate and unequal Americas, their mutual stars rising against the rising intolerance that metastasized into the Civil War — would clash at a distance. Douglass expressed disappointment with President Lincoln’s early toleration of slavery’s violent belligerence. ”Douglass also challenged Lincoln’s assumption that the border (slave) states of Maryland, Kentucky, Missouri, and Delaware would secede if the slaves were freed”, Stauffer notes.

Douglass frequently called Lincoln on his accommodationist approach to ending slavery, goading and prodding the new leader– at one point, Stauffer notes, saying he was ”a genuinely proslavery president”. The payoff came in September 1862, when Lincoln announced to his Cabinet his draft of the Emancipation Proclamation, ordering all slaves to be ”forever free” on 1 January 1863.

With emancipation Douglass’ attitude toward Lincoln suddenly changed. Never again would he so harshly criticize the president, even though he continued to disagree with him on many things. He knew that the Proclamation was a revolutionary document that turned the ear into a “contest of civilization against barbarism” rather than a struggle for territory.

The two finally met for the first time at the White House in August 1863. What followed for the remaining 20 months of Lincoln’s life was a friendship in correspondence and in person, an alliance by turns solicitous and confrontational, and every bit as complex as the nation’s racial predicament. In the waning months of the Civil War, Lincoln sought Douglass’ advice on bringing freed slaves into the Union ranks, and (bowing to his states’ rights reflex) over whether to abdicate control of slavery’s abolition to the states — an idea that Douglass aggressively, and successfully, put down.

Douglass saw Lincoln in a new light. The president was willing to go to far greater lengths in the cause of freedom than Douglass thought possible … Lincoln had long lagged his party; now he was ahead of it.

The friendship extended to March 1865; Douglass attended Lincoln’s second inaugural on the eve of the end of the Civil War, there in a crowd of thousands of Americans of all stations, from newly freed slaves to a disgruntled Southern actor named John Wilkes Booth.

Stauffer’s copiously researched, vividly written book (remarkably compact for all it contains) is a smart rejoinder to the usual suspects of Black History Month and the reflexive rituals of that annual February observance. Giants unifies the public platforms and passions of two American lives too rarely documented together in the mainstream historical narrative, or in the customary recitation of black American historical figures.

Stauffer’s book joins other, more voluminous and celebrated Lincoln biographies, putting the flesh of new revelation on the raw-boned frame of the Lincoln legend. And the author, a Douglass scholar for years, sheds welcome light on Douglass and his relationship with arguably our greatest American president during what may have been the pivot point of the nation’s history.

It’s proof not only of Stauffer’s scholarship but also his talent as a writer: The facts contained within the book have long been accessible in any number of other, independent sources. In an accessible, timely work that documents the inseparability of black history and American history, Stauffer has brought together two titans of American intellectualism, inseparable and equal.