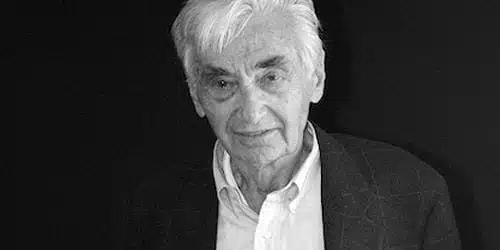

Professor Howard Zinn died on 27th January, a fortnight ago at the time of writing. Apart from the resigned rage one feels about the mortality of one’s heroes, my primary emotion was anticipation.

I had recently procured, with some difficulty, a copy of Zinn’s Passionate Declarations. I now had good reason to ignore boring daily life and work my way through Zinn’s declarations and legacy, a project as inviting as it is daunting. After a month spent far away from my library, the prospect of a reading list soothed me.

In the fortnight since his death was announced, I have spent many nights listening to his lectures, mining his books, and locating his prolific journalism. I have spent even more time trying to track Zinn within the maze of historiography: for all great scholars spin a web around them that can prove as revelatory as dissecting the shape of the beast itself. I gave myself a week to “get a grip” on Zinn, and have rarely underestimated a task more.

It was not the sheer profligacy of his work, since I never anticipated making my way through all of it, but the amazing variety of subjects that his writings and lectures suggested that did me in. It’s difficult to chart matters in an organized fashion when a single book (Passionate Declarations) can make you want to research everything from the Reformation to direct democracy. When one forays into the vast terrain of work inspired by, or transformed by, Zinn’s historiography the project looses all moorings in rationality. It becomes epic, spawning academic cottage industries.

I have no doubt such a fate lies in store for the late, great Zinn. I suspect he would be amused by all the posthumous interest, considering he spent his lifetime languishing in academia’s back closet, but I doubt he would be surprised. Genius is historically betrayed in the grave, after all.

I have read, to this day, two books by Howard Zinn. Dissident authors, especially American ones, are hard to find in India (our own we appear more indulgent towards). The exceptions, such as Noam Chomsky and Naomi Klein, prove the rule; as instances where popular demand outweighs self preservation in the profit calculations of the chain bookstores that are terraforming the Indian bookscape. Otherwise righteously self censored, the vaunted range of these book factories bloats right down the middle, leaving those of us who seek more exotic fare out in the cold.

Book politics aside, both the books I have managed to acquire have repaid all the ingenuity invested in them multifold. Both, in their very different ways, have amazed me by the breath of his knowledge and the depths of his insight.

I have a weakness for the interwar generation of polymaths, and Zinn entered my imagination firmly on a pedestal long before I found a copy of the People’s History of the United States. It is one that is yet to ossify, but our affair is still in the early stages of passion.

As writers grow familiar, they also get friendlier, I notice, inviting a degree of mockery and repartee into the relationship. This is where one starts clashing wits, one’s own knowledge of the world often challenging their version of events. This is a critical stage of the relationship. If the writing grows chilly, the rapport is never fully re-established. There might be respect, even reverence, but the banter ceases. One reads to appreciate, not to challenge and engage: a worthy endeavor, but the take-home, as they say, is lower.

On the other hand, if the argument should stay warm, reading a book can change your life. If this happens over a body of work, one commits the folly of loving a writer implicitly and unconditionally. Zinn and I aren’t there yet, but I see a bright future. He has written close to 20 books, from plays to polemics, their only apparent link his historical perspicacity. One, at least, I know to be a classic. While Passionate Declarations is an absorbing and informative anthology, the People’s History of the United States (hereinafter People’s History) is a wholly different creature: it is unique. There is no book quite like it, either in ambition or in orientation.

In a quirk of fate, I started reading a People’s History on 27 January 2009. I remember the date exactly because it was the day I started a two month internship that was to help me land a respectable job I would enjoy. I carried it with me to the office every day, reading in the stairwell whenever I felt as trapped as the factory girls it describes so vividly. I was working in Gurgaon, accessible only by road, the only part of India where global fashion seasons make a discernible difference to retail profits. Residents are frequently heard say nostalgic things like: “It’s just like a little piece of America” in their sales pitch to potential tenants.

It felt nothing like the vague childhood memory I had of the US, and reading Zinn only confirmed my hunch that Gurgaon was a uniquely Indian monster. It gets its patina by spatially concentrating the transcontinental elite that have exported canned “American culture” in the course of their diaspora: malls, karaoke bars, pizza joints, air conditioning. It remains, nonetheless, anchored in Indian reality, and to borrow from a well-known song, “The fundamental things apply/ as time goes by”. I felt adrift, overwhelmed by financial concerns and oppressed by distances that made it impossible to walk anywhere it was possible to see the sky.

Reading the People’s History was a comforting glimpse into realities where people living in less gilded, but equally stifling, conditions overturned history and wrested liberty from chance. If it is possible to assign agency to a book, it made my decision about the job, convincing me that golden cages chafe as much as iron ones and only cost more money. It showed me that everything the society I lived in was craving to be — this hopeful “Americanization” everywhere around me — was illusory; the problems that plagued my society were just as prevalent in its alleged model.

I ended that internship completely shorn of my romantic assumptions about the US, and indeed astonished at how much of my knowledge of American history was clouded by accepted wisdom and easy conclusions. I believed wholesale, for instance, the house version when it came to the first two of Zinn’s “three holy wars”. My skepticism for this century’s war mongering was already well developed, but Zinn stunned me by extending the logic of my reservations to wars usually treated as ideologically pristine.

The 1776 war won America independence from the British, the absolute virtue of which is undeniable to any Indian who has had cause to ponder colonialism. As an aside, one often commented admiringly on how surgical the Yankees were when it came to asserting their rights, especially when you compare it to our own messy century long struggle. It took Howard Zinn to show me the real costs and consequences of that war, and how the transfer of control worked out in the lives of the people who had created the revolution. It helped me understand our struggle better, and to confront such “clinical” wars with new ways to uncover their real costs.

His narrative was even more compelling when it came to the civil war and the hidden causes behind it, of which abolitionism was at best a minor footnote. I am not well disposed towards authority, but I have my fair share of favorite leaders. I don’t think any of them has ever been evicted from my hall of fame with as much celerity as Abraham Lincoln, after reading Zinn’s telling of that harsh, cruel, and ultimately pointless war.

Yet with the loss of romance came reassurance. It was tremendously liberating to think that Detroit was as doomed as Patna, and that people in mill towns in America had rebelled just as surely as the weavers of Ahmedabad at losing their livelihoods to machines. Suddenly, the urge to escape geography was not so compelling: the metropolis might broaden one’s experience, but it is unlikely to change one’s fate.

People’s History changed the face of American history; giving us, at long last, a definitive class history of the United States. It was a project of immense scope to undertake, since it required as much empirical ingenuity as conceptual imagination. The craft in writing history is in arranging facts to supplement narratives that cast fresh light on things lost to active memory. When one is writing a marginal history, from the point of view of people usually ignored or forgotten, just collecting the facts that have to marshal and bolster a 500 year history is an incredible achievement. It requires a historical detective to look at primary material and then draw out the story it has repressed, rather than the one it has extolled. To do so for 500 years of American history, the longest running nationalist history globally, leaves those of us who follow in his wake one more resource as we continue the tradition of confronting orthodoxy wherever we find it.

In the facts it used, the questions it asked, and the things it criticized, the methodology of People’s History is unabashedly Marxist. But it benefits from the fact that its author is unabashedly not, at least as conventionally understood. As a result the book never makes it feel like history is run by rooms of statisticians, like more strictly materialist books do. Unlike the dry pedantism of scientific materialism, Howard Zinn makes marxist history sexy, and accessible. The people behind the scenes are still people, and they have a considerable impact on how particular situations play out: as leaders, organizers, figureheads; even if the currents of history are immune to individual effort, Zinn remains sensitive to questions of how human beings and their conditions interact.

This is the touchstone of his historiography: the big changes to human destiny are never impersonal; but they are pushed along by forces that are too big for any single person to manipulate or comprehend, especially at the time of their unfolding. History is always pushed to crossroads by what Matthew Arnold once called “the turbid ebb and flow of human misery”. A great historian teaches how to balance the currents of history and the individuals that charted our course through them, and it is matter of great sorrow that we have lost such a gifted practitioner of the art. He has, however, left us a legacy both of words and deeds; one which will hopefully survive to tell people in coming centuries what life in the preceding ones was like, and why it was the way it was.

Even more optimistically, perhaps he will be remembered as the chronicler of nasty, brutish times from which humanity has since evolved, in so small part due to the efforts of Zinn and his colleagues to shine a light through the darkness.