Before he discovered filmmaking, a young Akira Kurosawa dreamed of the life of a painter. Kurosawa harbored aspirations of being a painter throughout his youth, but unlike Fellini, a professional cartoonist turned master director was mostly self-trained. And when he made the turn toward a career in filmmaking, it was a dream that he refused to leave behind. Instead, Kurosawa brought the talents and techniques of a painter to his filmmaking. With a phenomenal eye for framing remarkable shots, a fine understanding of contrast, and, in his later works, an ability to manipulate vivid color to outstanding emotional effect that only a handful of filmmakers could aspire to, Kurosawa cemented his legacy as not only a powerful storyteller but a director whose raw visual power is nearly unmatched.

Kurosawa hand-painted the storyboards and character studies for his films for some time, committing to paper images that would later spring to life on the screen. As a painter and filmmaker, Kurosawa stuck to his own style, informed heavily by traditional Japanese painting as well as European impressionists and expressionists, another arena of art where he answered to both eastern and western influences. These painstakingly crafted paintings formed the visual backbone of some of Kurosawa’s most lasting achievements.

Two of the most powerful examples of Kurosawa’s skills as both painter and filmmaker and his blending of the two media come toward the end of his career in the epic features Kagemusha and Ran. Kurosawa painted the storyboards for both of these tales of war, intrigue, and political strife in ancient Japan. The features share much in common stylistically, as well — each is dominated by long shots, feature beautiful landscapes, elaborate costuming, and intense color contrasts.

So similar in style are the films that Kurosawa referred to Kagemusha, largely considered a masterpiece on its own merits, a “dress rehearsal” for Ran, which would come to be seen by many critics as one of the pinnacles of Kurosawa’s exceptional career. In both films, audiences are treated to stunning pieces of visual craftsmanship that demonstrate one of Kurosawa’s most stunning gifts as a director — a distinctly painterly eye for color and framing that he turned to the camera, transforming the world around him into paintings as striking as any canvas. It is in this blending of cinematic and static visual elements that Kurosawa is perhaps most skilled.

While Ran demonstrates Kurosawa’s penchant for the sweeping landscape shot, it also emphasizes his skill in making his performers a natural part of that landscape. Kurosawa captures impressive visuals of the glory of nature in lush forests and rolling plains and infinite cerulean skies. But the characters that occupy these environments are just as important to the visual order of the scene, and often constitute forces of nature unto themselves. Armies on horseback gather like storm clouds threatening from high hilltops, implacable and menacing. As the film’s maddened protagonist shuffles aimlessly amid bleak backdrops of stone and sand, his presence makes the scene seem lonelier, the rock outcroppings that surround him more forsaken.

In one of the most stirring and iconic moments of Ran, we see Kurosawa take this trick to its ultimate level, crafting a living, breathing landscape from his actors. As the black doors of a castle close behind the ivory robed figure of Hidetora like the darkness that is soon to consume him, the once-great lord is left speechless and frozen in time before stumbling, not quite falling to the ground. All around him, his concerned vassals rise, then freeze in a stage painting that is equal parts painted landscape and noh-inspired staging. It’s an image that lingers, packing more sheer power and emotional impact into just a few seconds of film than many movies muster in whole running times.

The work that Kurosawa got out of his cameramen was second to none for much of his career, but placement, angles, and framing are especially important in Ran. The camera elegantly frames scenes with a visual artist’s precision, and the brightly garbed performers create human landscapes, be they crowds, courts, or combatants, within many scenes. This attention to detail and expertly choreographed action is on display throughout Ran, and makes for some of the films most stirring images, as when a gathered crowd of retainers splits open, their blue garb parting like a sea to reveal a spreading pool of scarlet blood staining the white stone of the road. It’s the greatest trick of a painter-turned-filmmaker as one image is deftly, almost magically transformed into another.

The editing process, too, contributes to the painterly quality that runs throughout Ran. Many of the film’s cuts are long, and often mostly static. Even in motion and action-heavy scenes, Kurosawa uses strict framing and shots that are held and repetition to create images that retain a static painterly quality even within the context of film. As a small army of soldiers rides, then marches, from the castle gates, the repetition of images and consistency of sound transform a multitude of shots into one image, simultaneously motive and static. Viewers are left no choice but to confront the enormity of the battle in the offing — without any cinematic short cuts or compression of time, it works visually as one image.

Later, in the wake of Ran’s grim, gruesome battle scenes — scenes which capture a number of images that would not be out of place in Goya’s Disasters of War — Hidetora again treads through a landscape of individuals, though this time it is the grotesque human debris of a battle joined and lost. A white, ghostly figure, as returned from the dead, Hidetora splits the legions of red and gold garbed soldiers as his stronghold burns on in the background. It’s an image that belies the power of this enfeebled figure still evident as all stop before him as he stumbles through the field of living and dead warriors into a lost place of fog and wind, his ruined domain left behind him.

A comparable display is presented in Kagemusha as a retreating line of troops is silhouetted against a bright, impressionistic sunset. Shot from a distance, each individual soldier is rendered unrecognizable — one part of a whole image from which it is inseparable, one moving part in a static image. These are uncomfortably long shots, providing no reprieve from the image as presented. Shots like these up the stakes on the standard voyeurism inherent in cinema, turning the tables on audiences by forcing them to watch past the point of their own comfort. They form, in a sense, a gallery of paintings that we’re not allowed to look away from. The persistence of the camera ensures that we will experience the vision of the artist not on our own terms, as we are used to and comfortable with from lifetimes of the museum-going set at our own pace, but on the terms of the artist, exposed unflinchingly and unapologetically to the image as he conceived and chose to convey it.

As opposed to Ran, Kagemusha is a deliberately slow work, its pace occasionally slowing to a plod, quietly watching its subjects, often in great detail in the most private moments. If Ran, then, is a film of landscapes, Kagemusha is a film of portraits — while close-ups remain rare, the film explores in detail the life of a man whose every moment is lived as if under a microscope. It is a work more concerned with minutiae and detail, valuing nuances of character and individual mannerisms over sweep and scope of story that makes Ran such an impressive spectacle and such a magnificent technical achievement. This is perhaps understandable, when the thematic differences between the two stories are taken into account. Where Ran measures the fall from glory of king and kingdom, Kagemusha is a more personal story of a man trying to fill shoes far too big for him.

Thankfully, a single out-of-place dream sequence aside, by the time Kurosawa began work on Kagemusha, he had become more comfortable with filing in color than he seemed in his first color feature, Dodeskaden. Kurosawa’s first feature outside of the standard studio structure. Dodeskaden is an often beautiful but equally often flawed film that sees Kurosawa’s use of color at its most immature and garish. It was also a dreadful failure at the box office, a fact that haunted Kurosawa. It also seemingly taught him some valuable lessons in understatement that would serve him well through the remainder of his career.

Kurosawa’s painterly qualities are the easiest to appreciate in these later works, filmed in vivid color that gave Kurosawa more room to roam visually, but they are present in his earlier works as well. In Rashomon, for example, Kurosawa uses the sun-dappled play of light and shadow through deep forest to craft masterpieces of light and shade that strengthen his stories. Using a palette composed only of shades, gradients, and a sense of urgent, active framing that is second to none, and a deep understanding of the makings of a strong stage picture, Kurosawa’s impeccable visual skill is on full display in monochrome here. Rashomon allowed audiences perhaps their first realization of Kurosawa’s formidable talents as a storyteller but provided only a glimpse of the masterful visual artist he would become. Stray Dog, meanwhile, uses an overheated Tokyo as its backdrop, allowing Kurosawa to bring the city and its residents to life. On the crowded streets and in cramped diners, the citizens of Tokyo form a living, breathing, sweating, bustling landscape for the action of the film, transforming the city itself into an adversary to Toshiro Mifune’s rookie detective.

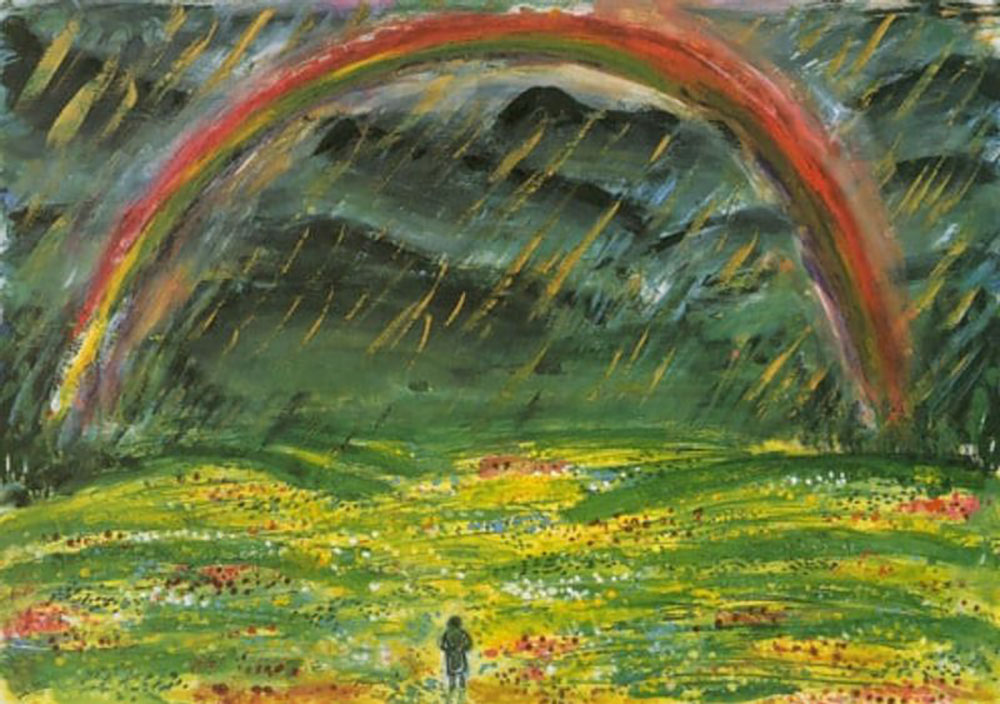

In one of his last films, Dreams, Kurosawa, never a terribly wordy filmmaker, largely eschews dialogue in favor of allowing his striking images and vibrant colors to tell his stories. What dialogue there is tends to be stiff and simplistic, wisely content to let the film’s visual power carry it. From the hellish furnace of Fuji in Red to the idyllic, wildflower dotted village of the watermill, from the magical drama of the Peach Orchard to the blasted, nightmare landscape of the weeping demon, each of the settings in Dreams exists in its own region of the mind, playing by its own rules. Its episodic nature renders Kurosawa’s Dreams a gallery of fables. From the sublime to the horrific, each notion in turn is given its moment. While thematically similar, each of the visions presented operates only according to its own inner logic. But each depicts, in some way, Kurosawa’s gift for engineering whole new worlds, small but complete universes that exist only as we gaze upon them, richly arranged and brightly hued canvases that feel at once fantastic and familiar.

Kurosawa would remain a painter throughout the span of his career. His canvas would be the forests, hillsides, and cities of Japan. He would eschew oil and watercolor in favor light and shadow, color and design. He would craft sweeping, epic landscapes and portraits at once cloyingly intimate and profoundly lonely. He would make the camera his brush, and the world his canvas.

This article originally published on 17 October 2010.