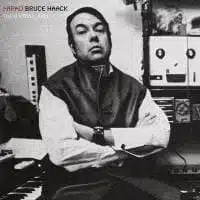

“I’m the party machine / No one like me,” declares a vocodered Bruce Haack on “Party Machine”, the stiff 1982 dance track that closes Farad: The Electric Voice. He’s half right. There was certainly nobody like Haack, a pioneering creator of electronic musical gizmos and author of some of the weirdest kids’ music the world has ever heard. In 1969, the man built a vocoder, named it “Farad”, and started singing songs through it. Farad is the first career-spanning compilation of Haack’s music for grownups, and it’s full of sci-fi kitsch, electronic acid rock, and even some stuff that sounds like country and showtunes over cheap Casio beats. But be warned: under no imaginable circumstances could any of this music start a party.

Haack’s name has long been a talisman for electronic music freaks like Add N to (X) and Beck, and sometimes you can hear the influence. Haack’s only major label album, 1970’s Electric Lucifer, blends electro chirps with Farfisa psych and hippy-dippy lyrics, a mix that seemed prescient in the late ’90s when everybody got tired of angry guitar rock. With its loping-on-the-prairie beat and twangy Jew’s harp effects, “Incantation” even resembles cinematic country music, an apt touchstone for a concept album about — what? — spreading “powerlove” to the frontiers or something. Trust me, it doesn’t matter. Lucifer only accounts for three of Farad‘s 16 songs, and once they’re over, things go downhill pretty quickly.

Not surprisingly, there’s a huge dip in sound quality from the Lucifer tracks, released by the wealthy adventurers at Columbia Records, to Haack’s later music, released on his own Dimension 5 label. The songs from 1978’s Haackula and 1979’s Electric Lucifer II are borderline unlistenable, and 1981’s Bite is only a hair better. The biggest problem is the beats: they’re murky, muffled things, seemingly overheard through the wall from a neighbor’s apartment and committed to tape. “Dinky” is not too strong a word. Two songs from Lucifer II, “Ancient Mariner” and “Stand Up”, even boast the same flaccid little pattern. Bite at least deploys its robo-drum fills with a sense of cheek, relentlessly and playfully, but there’s little life in the sorta-polka “Program Me” and the sorta-bossa “Snow Job”.

Lo-fi music sometimes gets a pass on normal standards of execution because it does other things well — maybe it creates a sense of menace or mystery, or it boasts Guided By Voices-worthy tunes. Haack’s music does neither. Despite using sounds that few people had ever heard, Haack wrote some pretty cloying songs. “Maybe This Song”, from 1971’s Together, is cheesy folk-pop the Byrds would have rejected. “National Anthem to the Moon” is a minor-key future dirge in the manner of Zager and Evans, but it lacks the crackpot details that make “In the Year 2525” so entertaining. The one standout — and maybe the best reason to hear this album — is the previously unreleased “Rita”, almost as catchy as the Beatles’ “Lovely Rita”. The beat still isn’t much, but Haack’s robo-voice is loose and plucky. There’s also a limp cover of John Jacob Niles’s “I Wonder as I Wander” — here titled “The King” — which would be a fine novelty for a holiday mix, alongside Bar/None’s The American Song-Poem Christmas anthology. You’d only have to hear ’em once a year!

Look, it’s obvious why Haack is important in the annals of electronic music. Famous musicians dig him, he beat Kraftwerk to the musical vocoder punch, and he released two albums called Electric Lucifer. These are noble achievements. But once you’ve convinced your friends that you’re cooler than them because you know about Bruce Haack, why on earth would you want to listen to his music?