Note: this article deals specifically with elements of Beautiful Escape: Dungeoneer that involve torture and sexual assault. It may be troubling for some readers.

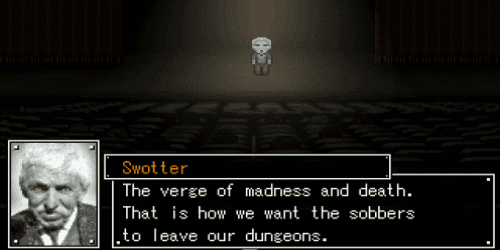

Today marks my third and final article on Beautiful Escape: Dungeoneer, the controversial independent game released earlier this year by psychotherapist Nicolau Chaud. I tend not to spend more than a couple weeks devoted to any one subject, but the swirling back-and-forth discussion surrounding the game in recent weeks has been exciting, thoughtful, and highly rewarding if you wish to read more about it. The designer himself has compiled a roundup of his favorite reviews, interviews and in-depth articles over at the game’s main site, which I would recommend.

In the course of writing about the game, I’ve refrained from lingering too much on my personal feelings regarding it — with the exception of remarks that I’ve made about the quality of the writing, but I attribute that not so much to the gamer side of my personality as it is that parasitic twin in the back of my mind who never got to be an English major. As a calculated metatextual counterpoint, it’s become quite effective. No one could argue that. But interpersonally, when friends and colleagues ask me about the game, my final line of the game comes down to something like this: “Don’t play it. Really. It’s not worth your time. I wish I’d never played it.”

I realize that I am on the edge of hypocrisy because I’m very grateful to have played it and come away with things to say that others find interesting. But on some level, I still feel incredibly uncomfortable and even disgusted with myself for having played it. Subconsciously I wish there’d been some way to observe the game without directly involving myself, but even a reading of a Let’s Play walkthrough would implicate me as participant in a culture of gamers who play by proxy, and I’d just swap direct digital sadism for voyeurism.

Film, too, is often voyeuristic, especially the body genre — by which I mean pornography, most obviously, but also slashers and body horror films that nest themselves in the empathic instinct. Sometimes stirring panic, other times exciting through a phantom sensation, we are simultaneously drawn to and repulsed by body genre works. In fact, we’re drawn to them because they’re repulsive, or taboo, or dangerous. This allure exists in games as well, but the performative nature of watching someone’s gameplay causes the distinction between participation and spectatorship to often blur. Like watching an amateur video, say. Or something that a friend of a friend of yours shot.

Let’s be real, of course; no living human being was harmed to create my gameplay experience, nor would they if I’d watched someone else’s. However, it reminds us of the controversies surrounding similar “game changers” that those in both the popular and the critical spheres tend to hyperfocus on: shooting civilians, committing terrorism, killing prostitutes to get your money back. Designers, rightly, remark that it’s down to the player to commit any of these acts, but are these scenarios followed through with in any manner that gives their consequences any more weight than a pile of dead Grunts in Halo? Or is it just entertainment with a garnish of controversy for taste?

To take it further — in Beautiful Escape: Dungeoneer, players gain an ally who gives them a “rape credit.” That is, you can hire a thug who will rape your victim for you, lowering their will to live. The actual animation is more like comical dry-humping, but it doesn’t matter. The player knows what it represents. And even more problematic than that is this additional point:

I used it.

Now how could I, as a woman, far less as a staff editor for a feminist media review site, do anything like that even by proxy, even in a simulation? Not once, but twice, even? The fact that I found I could best achieve the game’s elusive “beautiful escape” ending by using traps that progressively whittled down the victim’s life meters and that the rape tile just happened to be as good a compliment to the screwdriver tile doesn’t really excuse me. At the time, I separated myself from the action, but afterward, I found what I did completely repugnant. I regret allowing the game to acculturate me into treating this act as just the same as any other action that I could take.

I’ve written before here about player guilt, sometimes sloppily, other times more consistent with what I mean to say. What struck me quite explicitly when thinking about Beautiful Escape is that while interest groups will conduct study after study attempting to prove that video games make aggressive, inhuman monsters out of children (forgetting that kids are pretty aggressive anyway), few if any that I’ve come across have dwelt upon video games inspiring guilt. Which may in fact be linked to cases of aggression. Like I’ve said, the average FPS doesn’t give you a great deal of time or context to feel bad about the guys that you’ve gunned down. But certainly there are a few games (Heavy Rain, Metal Gear Solid 3) where killing or harming someone left me with my heart ripped out on the floor, and I believe that if violent videogames have a higher potential (that is, higher than as stress relief or entertainment, which are certainly valid purposes), it’s in allowing reflection on one’s actions.

Ian Bogost (Cow Clicker) was recently presenting his new book, Newsgames, at USC when he was asked about the possibilities of games as educative stories. Bogost shook his head, answering, “Games are bad for stories. We have other media that are good for that: movies, novels. Games are great for systems” (Ian Bogost, “Newsgames”, Annenberg School of Communication, University of Southern California, 30 Nov 2010). However, he said, these systems do provide for the exploration of consequences, and thus, finer understandings of cause and effect. While he was referring to newsgames specifically, it’s quite clear the methodology can be extended to all interactive media, if designers chose to employ it.

And some have. I would definitely count Nicolau Chaud among those. I feel it’s important to be confronted by those dark things most of us in our rational minds would never consider. For some readers, what I did will remain unacceptable, but I’m not writing this as a rape apologist trying to wave aside the significance of a game about torture. On the contrary, I take what I did very, very seriously. What a great way to teach consequences to a player within the safe space of simulation. I’ll never do that again.