A living American legend, albeit late in life, releases a self-serious album. Often, an esteemed producer and/or black and white photography are involved. Famous, respected artists whom the legend has influenced line up to lend helping hands and pay respects. Critics are right behind them. Johnny Cash’s exhausting American Recordings series is the prime example, but this trend has been applied to many othersl including, recently, Neil Diamond and Levon Helm.

It’s quite easy to view this phenomenon as a version of the de facto lifetime achievement Oscars that the film industry occasionally doles out. Martin Scorcese’s Best Director for The Departed and Al Pacino’s Best Actor for Scent of a Woman come to mind. Neither effort was undeserving, but the awards really seemed to be more in appreciation of entire careers, for the awards that hadn’t been awarded in the past.

And that’s kind of the feeling you get with Charlie Louvin’s recent resurgence, if you will. Louvin was half of the country-gospel duo the Louvin Brothers. Charlie and Ira Louvin had a handful of country hits from the mid-1950s to the early ’60s, but they were never superstars by any means. Ira, an alcoholic, died in 1965. The Louvin Brothers’ legacy has basically been their strikingly literally cover interpretation for their 1959 album, Satan Is Real. But they have, over time, emerged as cult figures. All the Beard Rock / “y’all-ternative” acts out there trafficking in close harmonies owe something to the Louvins.

Maybe that helps explain why in 2007, Charlie Louvin broke a 25-year retirement from recording and released a self-titled album which featured members of Wilco and Bright eyes, among others. The album garnered mixed reviews and hardly generated a groundswell of attention (you have to hire Rick Rubin to do that), but it was generally well-received. Even better-received were the live shows Louvin began playing, where people who probably never thought they’d get the chance were able to hear a legendary figure perform in person.

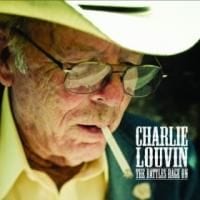

Louvin has since made record-making and touring his livelihood once again, releasing a live album and two more studio efforts between 2007 and 2008. Ships to Heaven went back to his gospel roots, and is considered the best of the bunch for it. Sings Murder Ballads and Disaster Songs took a more worldly, Cash-like tack. As its title might suggest, The Battles Rage On is the one where Louvin sings about war, and its effect on soldiers, families, and beyond. Louvin, a veteran of World War II and Korea, certainly has the experience and the right.

The Battles Rage On draws on songs from the 1940s, ’50s, and ’60s, and features three Louvin Brothers compositions. Though it’s not exactly John Wayne’s America, Why I Love Her, The Battles Rage On nonetheless takes the stereotypical country-western approach toward war and patriotism. The World War II-era “Smoke on the Water”, originally popularized by Bob Wills, is updated to include lyrics about Osama bin Landen and American bombers making a “graveyard out of Iran”. The album remains hawkish throughout, with invocations of brave, honorable men leaving their mamas and going off to fight for their God, their flag, and their freedom.

That doesn’t mean that there aren’t reflective or even poignant moments, though. The Statler Brothers’ Vietnam-era “More Than a Name on a Wall” takes the point of view of a mother looking at her son’s name on the wall, while Merle Haggard’s “I Wonder If They Ever Think of Me” is an almost existential narration by a prisoner of war. Both songs benefit from focusing on an individual where war is so often treated in general, faceless terms, especially in song. “Mother, I Thank You For the Bible” and “Weapon of Prayer”, both Louvin Brothers compositions, are among the strongest because they again take the emphasis away from sloganeering. In the former, the Bible that the solider’s mother sends into battle with him saves him in more ways than one, as it ends up stopping a bullet.

Many of the sentiments and feeling Louvin sings about are timeless, but the religious ones sound less anachronistic than the others. “What We’re Fighting For”, for example, was a country hit for Dave Dudley in 1965. A soldier in Vietnam somewhat naively questions the news he’s hearing from back home about anti-war protests. This sort of conflict must still occur today, but the soldier’s exhortation for his mother to “tell them we’re fighting for the ol’ red, white, and blue” sounds like an unconvincing argument from the days before TV cameras were attached to smart bombs.

Throughout, Nashville producer Mitchell Brown gives Louvin a tastefully simple musical backdrop, with acoustic guitars, upright bass, fiddle, and mandolin lending the album a suitably warm, if overly-clean, feel. It all points to the fact The Battles Rage On is all about Louvin. He’s in his early 80s and sounds it. At times, this is a plus. He can still hit the notes, and especially on the more uptempo numbers, his gruffness translates into spunk and determination. Here’s a guy who’s lived what he’s singing about. Also, though, Louvin can be heard gasping for breath throughout. Sometimes, he’s stabbing around in the dark for pitch and phrasing. This can make The Battles Rage On a painful listen, too, as you’re constantly reminded of the man’s frailty.

Maybe this is a fitting conundrum for songs about war, which, at its core, makes no distinctions for age, stamina, or even politics. If nothing else, The Battles Rage On, regardless of its debatable musical merits, makes you want to solute Louvin for making it this far.