Privacy in the United States and the rest of the world is quickly becoming extinct. Facebook, a platform for airing your business voluntarily, now has more than 500 million active users. When the choice of privacy is taken away from us however, things get invasive. Case in point: The US recently introduced the traveling public to the notorious TSA airport body scanners that photograph travelers — right through their clothing.

On a similar note, it was recently reported in Michigan that St. Joseph Mercy’s Saline, Ann Arbor and Livingston hospitals have obliged their employees who don’t get flu shots to wear face masks, even those who work in clerical offices (“U.S. hospitals mandate that workers get flu shots” by Robin Erb, Detroit Free Press, 09 December 2010).

Coincidentally, The Daily Mail has also published a report about a staffing company in Norway that forces its female employees to wear red bracelets when they are on their periods in order to let the bigwigs know why they frequent the bathroom so much. (“Boss orders female staff to wear red bracelets when they are on their periods” by Ian Sparks, Mail Online, 30 November 2010).

Such tyranny is reminiscent of Nathaniel Hawthorne’s The Scarlet Letter. Hawthorne’s tale of Hester Prynne, a married puritan living in 17th century Boston who has an adulterous affair with a minister, is the granddaddy of such busybodies in our culture. Prynne, whose affair results in her daughter, Pearl, is forced to wear a red letter “A” pinned to her breast for her crime of adultery, and is publicly chastised for her indiscretion, yet she refuses to give up Pearl’s father’s identity. Prynne is driven to the outskirts of town while being regarded by the town’s residents as a sinner and a slut.

Like most Americans, I read the book in high school. I remember being shocked by the public shaming of Prynne (this was before I knew much about the frequent mistreatment of women in other areas of the world) and I admired her as a rebel for not revealing her lover’s name, despite the scrutiny she faced. I also thought of her as a Christ-like figure in her willingness to accept her punishment while simultaneously refusing to succumb to a stricture she didn’t believe in.

When we read the book in school, we watched a film accompaniment – a four hour miniseries filmed in 1979, directed by Rick Hauser. Meg Foster played Hester Prynne and her strong features and excellent acting are still fresh in my mind. While the budget was low and the overall look of the production was pretty poor, the acting was terrific and the story stuck tightly to Hawthorne’s. As a result, it continues to be shown in class rooms to accompany the book.

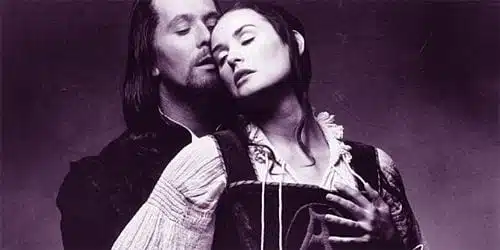

Something like the 1995 film version could never be shown in schools, and if it is, I’d be surprised. Fifteen-minutes into the film, Demi Moore is spying on a stark naked Gary Oldman. Directed by Roland Joffe, this adaptation is much looser than the 1979 version in more ways than one. It also takes liberties with Hawthorne’s story and plays up the sexy Moore-Oldman combination, making the film more of a titillating bodice/bonnet ripper than the powerful lesson it ought to be.

To be fair, the film states it is “freely adapted” from Hawthorne’s work, but that’s an understatement. Instead of a story about a strong woman victimized by an uptight community who uses her as a scapegoat, we get a steamy romance with softly lit sex scenes and Native Americans gone wild.

In Joffe’s version, Moore, who plays Prynne, is supposed to be viewed as a feminist, coming to the colonies ahead of her older husband (who later is believed to be dead) and taking a black female slave named Mituba to help her work the land. In the meantime, what she’s really busy with is undressing, Oldman, who plays Arthur Dimmesdale, with her big, brown peepers.

Masturbatory bath scenes ensue, and did I mention Mituba likes to watch? When Moore and Oldman finally do consummate their desires, Mituba watches them. This is soon after spying on her mistress naked in the tub. Unbeknownst to Moore, her husband, Roger (played by Robert DuVall) is still alive and hanging with the Natives whom the townspeople thought had killed him.

While the sin of adultery takes center stage in the novel, Joffe’s film makes a mockery of it, which brings to mind the tabloids that hound Hollywood stars these days and bring their supposed adulterous affairs into the limelight for the salivating public to eat up. Curiously enough, there were rumors earlier this year that Ashton Kutcher, Moore’s husband, had an affair with a young Hollywood blonde.

Unfortunately, Moore doesn’t have the acting chops to pull off a convincing Prynne. Instead of a strong-willed woman we get a brassy flirt. Oldman, who is normally an excellent actor, is overly dramatic (his sermon at the beginning of the film is long-winded and exaggerated). Perhaps it’s about as good as he can be, taking the hackneyed screenplay into account. When Robert DuVall, who plays Prynne’s fiery husband, Roger, shows up, fixed on getting vengeance for the affair, his histrionics are also unconvincing and laughable.

In addition to the movie’s cheap romance, the clichéd background choir music and the script (which is unfaithful to the novel) are evidence that Joffe’s attempt to recreate The Scarlet Letter is not only eye-rollingly absurd, but a slap in the face to Hawthorne. All anyone has to do is look at the DVD cover of the movie to see what I’m talking about. It looks like puritan soft-core porn. Overall, the film is anything but sexy — it’s downright corny.

As is often the case with classics, what could have been a brilliantly-updated film adaptation of The Scarlet Letter was consumed by the Hollywood machine that instead spits out a shallow and action-packed romp with a glossed-over ending. Hawthorne’s tale and Joffe’s film are both reminders (for different reasons) of how we can be stripped of our character in order to serve the needs of society.