Essay collections on significant bands seem to fall into two groups. On the one hand, they tend toward the purely celebratory. These are fan works, acts of devotion that are often little more than celebratory coffee table books with lots of text and not enough pictures.

On the other hand, collections such as these can be hard academic studies that employ critical theory to the artist(s) work in order make complex connections between cultural trends and music, representation and performance. These types of books certainly have their value but are frequently opaque to an interested reader unfamiliar with the secret dialects of academic theory.

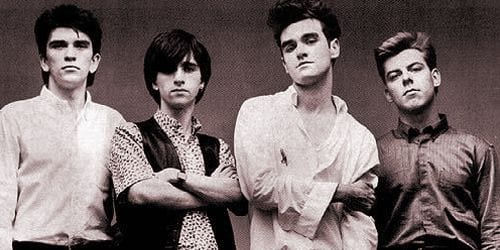

I’m pleased to report that the new essay collection on The Smiths, Sean Campbell and Colin Coulter’s Why Pamper Life’s Complexities? manages to avoid both failings. Written from a critical cultural and historical perspective, the scholarly essays are eminently readable. In fact, they represent some of the most incisive descriptions of the fey band from Manchester I have come across. They effectively show the reasons for the band’s massive appeal and explore their distinctive world, a world where rapid economic change and Thatcherism were remaking dear old Blighty into a twisted reflection of Reagan’s America.

Campbell and Coulter’s collection benefits immeasurably from the authors’ ability to ground their study in The Smiths’ historical and sociological context. Joseph Brooker’s contribution on the band and Thatcherism is paradigmatic for much of the rest of the collection. Brooker weaves detailed information about the politics of ’80s Britain with a layered understanding of “oppositional youth culture”.

This is as much an essay for someone seeking to understanding British cultural politics in the ’80s as The Smiths. Still, Brooker succeeds in explaining Morrissey’s complicated attitudes toward Englishness and tradition, a critique of conservatism that manages to be both anti-monarchical and an evocation of an older England. No easy feat that, but Brooker’s close exposition of “The Queen is Dead” shows how Moz pulled it off.

Another standout in the collection is Colin Coulter’s rather brilliant meditation on The Smith’s and “the hidden injuries of class”. Coulter shows that The Smith’s music “derive and retain much of their meaning… from the particular historical context in which they were conceived.”

Coulter really builds on a number of the other essays in showing how both the band’s lyrics (and often the sleeves of their singles) drew their strength from a nostalgic version of northern working class life. At the same time, Coulter compellingly suggests that Morrissey broke down and reconstructed working class masculinity.

Ceclia Mello’s essay on the influence of so-called “kitchen sink dramas” on the band is a great companion piece to Coulter’s. Kitchen sink dramas, social realist films that explored proletarian domestic life, became important expositions of often ignored elements in English life, beginning in the ’50s. Mello shows that Morrissey tended to paraphrase, and even directly quote, the dialogue from some of these films in his lyrics.

Though there are a number of strong contributions here, there are a few that, while stylistically well crafted, simply don’t make a strong argument. The best example of this is an essay on the influence of Catholicism on The Smiths. Much of the evidence marshaled to prove that the band made “extensive use of Catholic themes” actually tends to make the opposite point. The fact that Morrissey spoke frequently about his Catholic upbringing, and in highly negative terms, mainly shows that he put distance between himself and his background rather than that it had a determinative influence. Moreover, what the author reads as religious imagery is, more often than not, simply folk idiom borrowed from working class life (“Heaven knows I’m Miserable Know” is not, despite the author’s assertion, an example of the language of the sacred).

This is a book that tries to examine The Smiths as a band but, not surprisingly, the long, pissed off shadow of Moz hangs over everything. This is true even when the authors are making the case that the extraordinary licks of Johnny Marr deserve equal billing (have a quick listen to the torrent Marr unleashes on “Shoplifters of the World” if you don’t believe me). The mostly forgotten Andy Rourke and Mike Joyce get a mention here and there, but should have gotten an essay of their own. This would have been a real contribution to Smithiana, but it doesn’t happen here. Many of the essays are dependent on close explorations of Morrissey.

And, really how could it be otherwise? Obviously, it was his genderless crooning, its bizarre inflections fusing pop, rockabilly and R&B that gave the lads from Manchester much of their distinctive sound. Many of the essayists dwell, legitimately on Morrissey’s outspokenness. Most of these scholars seem to suggest that it was his stubborn refusal to accept Thatcherism, the monarchy, and even the accepted construction of what a rock star should be that helped to define the band’s importance in popular culture.

Morrissey in fact did publicly refuse all of this, announcing that he was celibate, urging vegetarianism in the harshest and most scolding of tones, suggesting that he hoped someone would assassinate Thatcher and appearing on stage with gladiolas in his back pocket and wearing a hearing aide. This sometimes not so charming man was, rather tragically, the key to the Smith’s amazingly creative output and also their quick and dirty implosion. The archetypal boy with the thorn in his side, he was, by all accounts, the genius who was impossible to deal with. He’s also the genius who will always be, for better or worse, the focus of pretty much all the writing about The Smiths.

Despite what I noted above about the accessible nature of the book, academics in pop culture studies should not fear that these essays are theoretically naïve. Campbell and Coulter make clear that the volume is guided by Simon Frith’s work Performing Rites, and the idea that scholars should move between critical evaluation and a very open acknowledgement of the personal value of a pop culture artifact.

Fans of The Smiths, and anyone personally or professionally interested in British popular culture, must read this book. This collection is really the epitome of what pop culture criticism can and should be.