Articulating the search for excellence, for an actor, is a famously problematic thing. At the best of times, it’s difficult for actors to strike a balance between the seriousness of purpose required to produce great Art, and the self-awareness required to realise that it is, after all, a rather silly way to make a living.

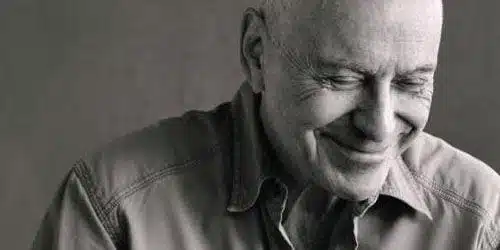

At first glance Alan Arkin — not only one of the fine comic actors of his generation (Little Miss Sunshine, etc.) but a notoriously prickly, uncompromising type within the industry — would seem to be the ideal man to navigate these awkward waters. It’s certainly typical that he would be the one to skip right over the mundanities of the conventional celebrity memoir format and head straight for the serious business. An Improvised Life is Arkin’s personal story only in terms of his ongoing relationship with his craft.

His professional life must necessarily be sketched in a bit more detail, albeit still mostly in the context of examples of the craft or revelations about it. Arkin fans should very much enjoy the brief but charming tales of friendship with Groucho Marx and Tony Perkins; and they will no doubt smile tolerantly at his extended bemusement with the notion that “… in exchange for celebrity, we owe the fans something.”

He establishes himself fully as an intelligent man, serious but not pretentious, who writes with graceful honesty and a welcome economy. He has things to say — from both sides of the camera — about performance as a vehicle for emotional reality, and its attendant effects on the performer’s psyche, that even the casual film fan can recognise as valid. The soul of an actor’s art, Arkin argues, lies with his ability to improvise, in finding the courage to abandon self and become open to possibilities… and that leads in turn, quite naturally, to self-examination…

…And this is where things start to go off-balance, because he never loses the seriousness. This process of turning inward has naturally inclined him not to bemusement — though he comes close in spots — but to earnestness. That particularly deadly earnestness that compels one to record every last insight, not because they’re entertaining, incisive or even particularly original, but because they’re important. Even an internal dialogue intended to provide some perspective, featuring a Martian curious about this bizarre thing called ‘acting’, somehow contrives to be imbued with Meaning.

This relentless lack of balance leads to some actively jarring passages, in which Arkin apparently does not see any difficulty with arguing for a holistic approach to acting, with an emphasis on awareness of the whole piece rather than simply one’s own part, while persistently refusing to provide more than the barest hint of his own external context. By the time he gets to the therapy and New Age mysticism — which he does rather quickly — even the most dedicated Arkin fan, film buff or aspiring artist might themselves feel bemused. Arkin is exuding the zeal of the self-help author, rather than the artist. As the eventual segue into tales of his performance workshops tends to confirm.

On reaching those final workshop chapters, it’s impossible to ignore how much of a relief it is to be spending time in someone else’s creative process — and even then Arkin must underscore the students’ stories with his own thoughts on what their reactions mean and why.

In the end, I found myself ready and willing to read anything Alan Arkin cares to write — except on the subject of performance. Enough, already.