On the bountiful disc of supplements included in the Criterion Collection’s presentation of Alexander Mackendrick’s Sweet Smell of Success, filmmaker and Mackendrick protégé James Mangold likens the film to a nature documentary. Considered in this context, Ernest Lehman’s characters — enlivened by writer Clifford Odets, arranged in space by Mackendrick, and strikingly photographed by James Wong Howe — form a group of opportunistic, press-obsessed predators in a claustrophobic city as cutthroat as the wilds.

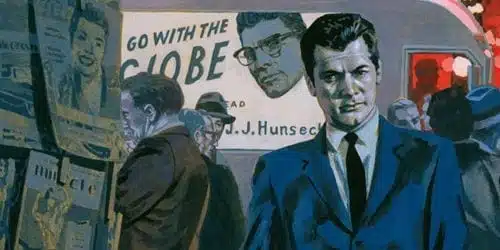

Emerging from this coterie of villainy is the film’s true heavy: Broadway gossip columnist J.J. Hunsecker (Burt Lancaster), a character based on storied real-life columnist Walter Winchell. Hunsecker haunts by proxy the proceedings of the film’s first act. An advertisement and column bear his likeness, and the characters in orbit around him discuss Hunsecker and maneuver to intersect with him. None is more interested in face time with him than Sidney Falco (Tony Curtis), a press agent always on the make, on the take, and desperate for a hot story to break.

The main drama that arises in the film concerns Hunsecker’s anxious sister Susan (Susan Harrison) and her brother’s attempt to destroy her relationship with jazz musician Steve Dallas (Marty Milner). For Hunsecker, Falco is merely a means to that end, and Falco is more than willing to be a pawn and exploit many others in the process if it means he can advance professionally toward the sweet smell of success.

As many have commented, the film’s exposition is buried so deeply within the present action that the viewer spends much of the running time piecing together the nature of the character relationships. No one explicitly states why Hunsecker is so creepily protective of his sister (a relationship modeled after that of Winchell and his daughter). Nothing in Steve Dallas’ character seems particularly objectionable. And although we know that Falco has done some dirty work for Hunsecker in the past, its specific darkness and depth are unplumbed.

What is apparent is the need for predator and prey to keep moving forward in the urban jungle – an environment that more often than not rejects scruples altogether. Odets’ script snaps and pops with one liners and repartee, but no single exchange goes to the film’s cynical heart more effectively than Hunsecker’s conversation with Falco about Dallas. He asks Falco, “What’s this boy got that Susie likes?” Falco answers, “Integrity — acute, like indigestion…I never thought I’d make a killing on some guy’s ‘integrity’.”

In Mackendrick’s films, integrity isn’t always a liability or a quality for the unscrupulous to exploit. Sometimes its function within the plot is absence or conditionality. In Mackendrick: The Man Who Walked Away, a 1986 documentary included in the supplements, actress Joanna Barnes says that the director’s final film Don’t Make Waves (1967) is a difficult film because all of the characters are unlikable. Even one of his most well-received films, The Man in the White Suit (1951), doesn’t have a traditional hero at its center. Mackendrick notes within the documentary that Alec Guinness’ Sidney Stratton is no more moral than the industrialist villains in the film. Stratton’s integrity is, too, up for grabs, but the other characters simply don’t bribe him with the right things.

Criterion’s release of Sweet Smell of Success draws attention to the contrast between the shady characters of Mackendrick’s films and the good nature of the director himself. In James Mangold’s video interview, he describes his mentor/teacher as having a “winning sense of modesty” about his own work. Especially in these segments that discuss his later career as a professor at California Institute of the Arts, a portrait emerges of Mackendrick as a gentle, caring classicist. Through Mangold’s interview and other stills and footage of the director’s educational tools, we are privy to those things Mackendrick considered to be his foremost storytelling skills. Above all, he saw himself as a director of visualization, telling stories as series of individual images moving through time and space.

Sweet Smell of Success reflects this classicism, but as Mangold notes, it is a strange film that also knowingly breaks some of the very rules that Mackendrick supported. The conclusion of the film, in particular, is not as tidy as many audiences might desire. The lack of satisfying comeuppance and failure to restore moral order reflects the tabloid culture the film explores. In another video interview included on this release, critic/historian Neal Gabler discusses the impact of Winchell on the entertainment value of contemporary journalism. Gabler observes that the very layout of a tabloid is an image of a chaotic world, far less orderly than respectable papers would have us believe. More than half a century after its release, Sweet Smell of Success jolts us with this very message. The Falco-Hunsecker hustle is very much alive, in the presently ubiquitous tabloid journalism and its sacrifice of integrity for celebrity.