Bob Dylan needs a poet, not a biographer. Indeed, the construct “Bob Dylan”, psychopomp for American culture, is itself a kind of poetry rather than a person and performer. Maybe there’s still an aging Robert Zimmerman wandering around in Minneapolis and this new identity is just something that was born out of all the suppressions and repressions of a modern America that wanted to ignore its past and the bard who refused to let it.

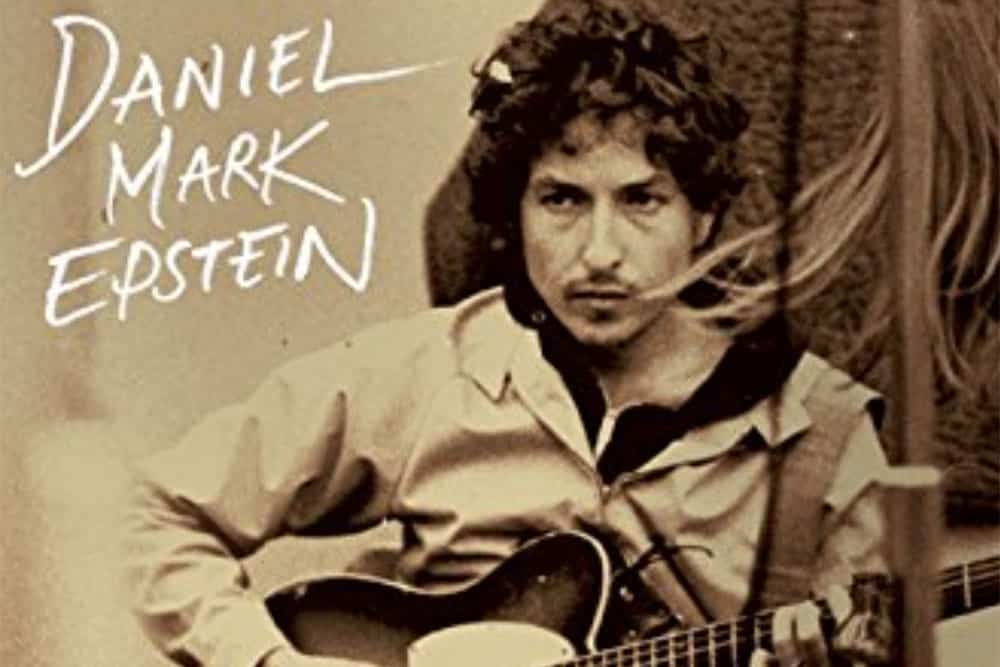

Daniel Mark Epstein’s The Ballad of Bob Dylan paints an impressionistic biography of Dylan that draws its inspiration from the numerous other impressionistic images of Dylan in American popular culture. Pennebaker’s Don’t Look Back plays a significant role here, as does Dylan’s Chronicles. The Ballad of Bob Dylan is in every way aptly titled, as it often works as a meta-narrative about Dylan, truly a ballad of Bob Dylan but also a ballad about the many ballads composed about him before.

You may be thinking that the last thing the world needs is a meta-narrative about Dylan. A flood of works followed 2007’s I’m Not There, itself building on an army of previous writers and artists attempting to come to grips with the America Dylan invoked, an America transubstantiated into beat poems meet blues songs meets every genre that ever issued forth from a plantation field, railroad stop, cowboy camp or textile village.

Epstein does something a bit different than most, combining the creation of a solid biographical exploration of the human being bundled up with the cultural myth. His previous work as a historian of figures as diverse as Nat King Cole and Abraham Lincoln serves him well.

The Ballad of Bob Dylan is built around four concerts Epstein has seen over Dylan’s 46-year (!) career. These chapters ground the book in Epstein’s poetic rendering of the American songster and provide signposts that keep us following Dylan’s rambling road that took him from a Jewish kid in Minnesota obsessed with roots music to the international star who fused rock and folk. Further down the road, Epstein introduces us to the born-again Christian, the singer who found continued commercial success in the ’80s by touring with the Grateful Dead and Tom Petty and finally, the prophet on “the never-ending tour” putting out albums in his 60s like Love and Theft that manage to summon the ghosts of Charley Patton and Abraham Lincoln and to put us in mind of Woody Guthrie and Walt Whitman.

Plenty of good works explore Dylan’s massive musical corpus, but Epstein surpasses them in exploring Dylan’s personal relationships. This at times becomes a withering look at Dylan’s treatment of the people in his life; friends, lovers, and family members. Epstein looks unflinchingly, shattering some of the well-worn images we have of Dylan and his times.

The author’s look at Dylan’s rapid rise to international superstardom in the mid-’60s is a good example. The death of his relationship with Suze Rotolo, the young woman in the now “Grecian Urn” seeming image on the front of the Freewheelin’ album, is unpacked during a period in which youthful arrogance turned Dylan into something of a monster. His treatment of fellow folk singers was atrocious, as was his infamous ugliness to sometime paramour Joan Baez on his 1965 English tour.

Epstein refuses to look away from this side of his hero, allowing him to explore and explain Dylan’s transition from folk singer to rock star without reverting to simplistic renderings of the tale. Too many heroic tellings of this story focus on Dylan plugging in his guitar and giving those square hipster folkies in sweater vests a rock ‘n’ roll show they would never forget or forgive. Epstein shows that the change was more complex than this and examines the story concerning the end of Dylan’s affair with Baez. Fans will be glad to see that this is no easy hack job on Dylan but rather a compassionate exploration of a stumbling artist who knew a hard rain was a-gonna fall even amid his youth and fame.

Some readers may feel that The Ballad of Bob Dylan suffers a bit from how Epstein uses his primary sources. There’s a lot of raw material here, interviews and sources that feel unprocessed, materials that it would have been good to hear Epstein transubstantiate into his own poet’s voice. At the same time, the book serves as a good introduction for those who want to know more about the mountain of reflections (music, film, and memoir) that have tried to come to grips with Dylan’s meaning.

Hopefully, The Ballad of Bob Dylan will encourage more people to see the 2003 Larry Charles film Masked and Anonymous. Epstein writes appreciatively of the failed film, calling it “a picture of the world as Dylan sees it, slightly exaggerated.” Set in a post-apocalyptic America, Epstein points out that it is populated by the same characters who appear in Dylan’s music and tells a story of musician Jack Fate (Dylan) transforming despair and emptiness into art.

Panned by critics as “incoherent”, Masked and Anonymous includes some outstanding musical performances and an extraordinary soundtrack every Dylan fan needs in their collection. The Magokoro Brothers do a cover of “My Back Pages” in Japanese, and Shirley Caesar belts out “Gotta Serve Somebody”. What more do you need to know?

Epstein’s fine work is far from the last word on Dylan or Dylan’s America. (It is, in fact, the second great Dylan book I’ve reviewed this year for PopMatters. See also Sean Wilentz’s Bob Dylan in America review, here). This is partly because, somewhere along the way, Robert Zimmerman disappeared forever, and Bob Dylan was born. And then Bob Dylan passed from folk to rock singer to hierophant of American culture, a loving and thieving fiction who tells us more truth than we can usually hear or feel or bear. Epstein is the poet Dylan deserves.