There are few records that I heard last year that impressed me as much as Constant Companion, the sophomore release from Canadian journeyman Doug Paisley.

Boasting an impressive list of supporters and influential fans (including Leslie Feist, Garth Hudson, Daniel Lanois, and Blue Rodeo) and earning a 4-star review in Rolling Stone, Paisley quietly crept up the year-end Best Of lists for many critics north of the 49th, even though he generally failed to find a wide audience for his material. Part of that was because, though the record was released by Brooklyn-based label No Quarter, and enjoyed fairly wide distribution in the US and the UK, it remained largely unavailable in Canada as anything other than a download — which is bizarre, and perhaps speaks more to a confused and confusing Canadian pop music climate than anything else, since the only thing that isn’t immediately accessible on Paisley’s record is its grotesque cover art.

Yet for anyone who’s followed the convoluted and frustrating history of the various Canadian culture industries, this isn’t anything new. In fact, although Paisley plays down the significance of this problem — “a lot of that story got kind of inflated, you know?” — he does admit to having had a harder time than he thought he would when shopping it around in his hometown. “A lot of labels’ reactions weren’t necessarily to do with what they thought about the album,” he told me over lunch at Aunties and Uncles, his favourite Toronto eatery, “but they had to do with the reality of the Canadian music industry. Then, it got turned into this notion that supported this piece about how we don’t support our own, and we don’t like our own music, and all this kind of stuff. I think it got caught up in that more than it was really representative of that.” Maybe. But, it still took the intervention of an elder statesman in the form of Andy Maize (of Canadian alt-country pioneers The Skydiggers) before the label Maple decided to take him on. “He really helped me out a lot,” smiles the ever-friendly Paisley, as his old pal comes by to take our orders.

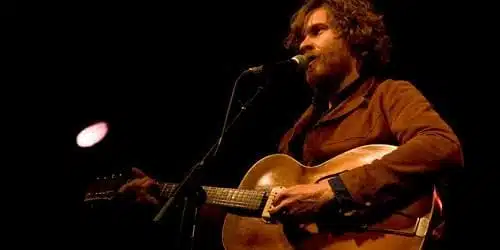

It’s hard not to see why people are drawn to him, why they want to help him out. A tall, thin 30-something with a ginger mustache and a trucker’s cap, Paisley is a bit of an overgrown kid. His bright eyes and winning smile invite you in, but it’s his thoughtful and articulate conversation that keeps you in your chair. He’s the kind of guy you want to support, to collaborate with, to share with others. Though still basically an unknown singer-songwriter (at least to most folks outside of the indie-folk genre), he has already toured the United States with the underground luminary Bonnie “Prince” Billy (invited as a favour from a friend who was involved in the tour), recorded with world famous pop star Feist (“I was really proud to sing with Doug”), and scored living legend Garth Hudson as a sideman (introduced to him by Daniel Lanois, no less, yet another favour). There is being connected, and then there is the other thing. This is the other thing.

As I have found myself exclaiming to fellow music critics, fans and friends over the past eight months or so, Constant Companion is gorgeous singer-songwriter stuff, and perfectly executed. Mellow, warm, and thoroughly melodious, Paisley’s voice is charmingly humble, homespun and timeless, but there’s a subtlety to his delivery that sneaks up on you by the third or fourth listen, and it starts to get that old sweater feeling. You want to crawl inside for awhile. The production is understated and immediately reminiscent of classic early-1970s masterworks from the golden days of the singer-songwriter genre. But, as much as Paisley’s material recalls that sun-dappled era, there is a forward momentum to his lyrics that is unmistakably relevant, current, immediate. As Feist told another interviewer, stealing unspoken words from my mouth, “His way with words fits my life like a worn-in old shoe; you know, comfortable and familiar but helps me bound around and climb and leap, and ponder the things I’ve gotten too used to with fresh eyes.”

Indeed, Feist offers up a lovely duet on “Don’t Make Me Wait”, a tricky call-and-response between two troubled lovers, and her unmistakable voice works wonders snaking around Paisley’s honeyed flow. But, for many listeners, it is likely Garth Hudson’s spectral keys which will be the most surprising and welcome contribution here. How did a virtual unknown manage to get Hudson to become involved in his record? “A friend of mine is friends with Daniel Lanois. And I said something to him like, ‘Hey, Garth Hudson opening your show was just phenomenal.’ And he said, ‘Well, he loves to play with people, he loves to work on recordings and things like that.’ He, basically, hooked us up, gave me the introduction and that’s how I got in touch with Hudson.”

* * *

So, you just fell into it with Hudson?

It was just crazy timing. It was actually kind of a crazy thing because I had these really deliberate plans for the album, and I knew when I was going to do it … I almost knew the order I was going to record the songs in and everything. And I had never been that methodical before, but that was the direction I was heading in. But then I got a response from Garth that was like ‘We’re in town tomorrow, let’s do it the day after that.’ And, I actually said: ‘I can’t do that.’ [laughter] I was like ‘No, that’s impossible. There’s nothing I’d rather do, but I can’t do that.’ And I hung up the phone, and just … I had the realization that I just have to do that. And so we threw it together. But that was serendipity, I think. I was getting too methodical. Too deliberate. And this basically forced me to finish the tunes for him, get them ready, find a studio, get some musicians … a little bit of chaos was good.”

Garth Hudson is a pretty risky sideman. I mean, I’m sure that everyone wants to think they can play with him, but he’s such a singular musician, his sound is so unmistakable. Were you convinced that your songs and his keys would work together?

At the time, you’re not entirely sure what he’s doing! Actually, it’s a funny thing: because we recorded on tape, we didn’t get to listen to it for about five or six weeks after we recorded it. We’d kind of imposed on [Canadian musician] Hayden to use his house — I didn’t even know him that well. We went in there for like a day, and that was kind of the end of it. And then, more than a month later, we were like: ‘Let’s listen to that now.’ And at that point I was — and obviously it was so exciting working with him, there was no question about that — but there was this feeling the whole time before I heard it where I was like: ‘I don’t know if we really got anything.’ Like: ‘I don’t know if it’s going to work, what it’s going to be.’ But it had worked, you know? And I think that’s a real testament to his playing. The feel, the logic of it … it’s a creeper, you know? It just grows and grows.

You can actually hear what I was wondering about — he plays, on the one hand, a kind of typical organ sound, more like a Hammond or a Lowery that you might have played back in the day, but then he’s also playing this keyboard that has this 80s synth kind of keyboard sound. Two totally different sounds, two different parts, at the same time. And, in terms of my aesthetic, in terms of what we were looking for, I think my initial reaction was: ‘Yeeeeeeah, we might not use a whole lot of that synth part. We may not use any of it!’ But then when I dropped him off, he said to me, he’s like: “Make sure that you use both parts, because I really think that they work together.” So, at the time I felt a bit conflicted about that.

* * *

The idea of inner conflict, of duality, is a powerful thematic current on the record. From the oddball cover art (Paisley sitting beside “himself” wearing a felt mask of his own face) to the title Constant Companion to the subject matter (songs like “O Heart” and “Nobody But You” both appear to be love songs, or is it pep talks?, to the “self”), the record is shot through with a sense of a duality at the core of being. And it is not unrelated that the main thing that has impressed people about this album is its remarkable intimacy; the record often feels like an internal dialogue we have come to overhear. There is something about the understated analog production — the warm presence of the guitar, the vocals — that I find impressively sensual, even moving. It puts me in a dark place, but not necessarily a melancholy one. It’s darkness as in dimness of light, not of hope. And, I suppose what it is that makes me return to this record (more than anything else, including the very pretty melodies) is the fact that I am pretty sure that every folk singer (or singer-songwriter, or what-have-you) wants to make this album when they sit down with their producer. They want their record to be powerful but not pushy, sensitive but not maudlin, heartfelt but not schmaltz. In other words, despite the fact that I fundamentally enjoy this record, I also am awed by its success at conveying among the toughest, and rarest, of all musical messages: emotional honesty.

* * *

So, I guess my question is, um, how did you do that?

In terms of my aesthetics, I guess I listen to a lot of warm sounding music. I listen to a lot of stuff from the early 1970s, and … I don’t necessarily believe that I’m such a technician that I can translate my aesthetics into what I want to make, you know? [ …] But, I think it’s really deliberate. It’s deliberate in the sense that I had the songs for a long time before I recorded them. You know, I had lots of them since my last album which was quite a gap. In some cases they were even older than that. And, I was working on them for like ten, twelve months, without doing any recording or anything like that. And that, to me … I don’t know how other people work up their songs for an album, but by the time I had come to record it, I had played it at home hundreds and hundreds of times.

You knew what you wanted.

In one sense, you’re so comfortable with the material that you can be pretty flexible, but in another sense there’s not a lot of spontaneity or craziness. You kind of go in, and it’s almost like it’s already decided for itself what it is going to be. And I think that made me more comfortable than if we were wondering if maybe we should put a guitar solo here, or maybe we should put strings in … sometimes you almost just want to throw things at it, you know?

This debate is classic. Does over-production get in the way, in your view?

I think that when people really value those kinds of sounds, or some kind of period, they can work too hard to try to recreate it. And, I think that so many of those kinds of attempts, or what I think are attempts, really fail. Maybe they succeed in other ways, but fail on that level. But I guess the obvious alternative is when people make that stuff that’s just so heavily produced. “New” music. And I guess in both cases I kind of see that you can have such an influence on the music and the songs in that production stage. Which — I just don’t believe in that approach, you know? For me, I guess it’s a kind of submission thing. Well, these are the lyrics, these are the chords, I know how to play it really well on the guitar, I know you’re all really good musicians, let’s just do this.

Throughout the record, there is this thematic coherence. Duality, whether emotional or physical, spiritual even. How conscious were you about crafting this?

It happened pretty spontaneously. I think a lot of the meaning really happened in hindsight. It wasn’t like an ongoing theme to keep returning to. But, the cover, it was a double exposure. We kind of wanted the other guy with the mask to be a little bit inadequate. His body language is just a little bit … he’s slouching. Partly because we wanted to differentiate the two characters on the cover, but I guess, and again, I really think a lot of this is hindsight, but it was kind of this idea that he’s this part of you, this really integral part of you, but also maybe the part that you don’t always want to put forward. And one example of that is for a songwriter, you might actually give a character a part of you that you don’t even necessarily like, or you don’t necessarily want people to know about. Sort of like that weird brother that lives in the attic?

It’s funny because you use the word deliberate a lot, but then you back away from the idea that the record is deliberately crafted, thematically.

I think most musicians find themselves in this situation, where you have 15 or 20 songs to choose from. But, I do think that the songs are really entities, and I can’t imagine doing anything deliberate during the songwriting process where I’d be steering the songs into some relationship to the other tunes, you know? But, maybe in that selection process, when you’re choosing from a larger pool of songs, that happens. But, whether there was a certain period I was going through where I was doing a certain kind of songwriting? I can’t think of anything specific. There was no Blue period, or something like that.

I once got asked if, since I have this really specific sound, if I ever wrote a song that was just anomalous? That just didn’t fit in? And I’ve been thinking about it. And, you know, actually, where they come from, where they start out, they are all anomalies. And some of that synergizing is around what seem, to me, like these more superficial elements. Like the players, and the way your voice sounds at that point. But, no. Short answer: no. There wasn’t any period where, like, I had a motorcycle accident and so … nothing like that.

* * *

As we linger over a long lunch — it was an hour and a half all told, an eternity for an artist to give to an interviewer — it becomes clearer to me with each passing moment why this emotive, folky music heats up in Paisley’s hands when it often lies cold in others. There is no irony here.

None at all. Here is a guy about to go out on tour, the day before a big show in his hometown, as calm and gracious and unaffected as can be. He speaks freely. There is no front, no attempt to impress or to appear “cool”. He’s been doing this for a long time, and it’s finally starting to work out for him, but he seems like one of those guys who won’t change a thing when he gets under the lights. And then his pal, the owner and operator of the restaurant, comes by to refresh our coffee, and he asks Paisley if he can do some carpentry for him. “I built some of the stuff in here,” he tells me, at least as proud about that as about working with the guy who wrote the riff in “Chest Fever”.

* * *

Everyone wants to write sensitive emotional music without sounding sentimental or weepy or like a 16-year old diary poet. And lots more people fail than succeed. But you pull it off.

You know, I’ve listened to and played a lot of country music for a long time. And maybe I have a less complicated relationship to it than other people might. I don’t have a nostalgic relationship to it, I don’t have an ironic relationship to it, and I no longer have an overly self-conscious relationship to it. I just genuinely like it, you know? And I no longer feel that I have to explain to my friend why I like George Jones or why I like Don Williams Stuff that people might find maudlin or saccharine or whatever. I don’t know. Maybe the benefit of that is you’re able to embrace those things in your own music without feeling like you have to make some kind of apology or disclaimer. I remember when I first started out and played in a bluegrass band, and we did gospel songs. And there’d always be this kind of felling like we’d have to say: ‘I’m really sorry but we’re about to sing a song about Christ. But don’t worry, we’re not even Christian, and we’re not proselytizing.” You know?

But then, now, I just play the song because I like the song.