Starlight Theatre has always been a top-notch venue for the performing arts. At once an intimate, outdoor concert space, it also is a stage for its regular summertime musicals. It holds 8,000 people; nearly every seat in the place provides a decent perspective. David Bowie put on a most rewarding and standout concert in 2004, playing songs that spanned his career. Arcade Fire’s recent April gig also proved efficacious. But Starlight has reliably lured a number of Broadway plays, and acclaimed actors, to Kansas City too. Rodgers and Hammerstein’s beloved musical, The King and I, starring Lou Diamond Phillips, was perhaps the finest introduction to the theatre’s seasonal lineup: 9 to 5, Guys and Dolls, Cinderella, Mamma Mia!, and Xanadu. Tonight’s rendition was, in fact, a critical and inimitable one. With Lou Diamond Phillips at the helm, The King and I was almost certainly flawless, credible, and instructive.

This musical’s narrative concerns Anna (Rachel Bay Jones), an English teacher called to Siam by its reigning monarch (Lou Diamond Phillips). It dissects a myriad of topics, including politics, colonialism, gender, culture, romance, and, in fact, religion. Siam (modern day Thailand) is officially a Buddhist kingdom, and in one of the more hilarious and overtly comedic scenes, the King demonstrated his presumably learned critique of Christianity (Anna’s faith). It was also quite serious in that Phillips was most convincing during his pointed ridicule of The Bible; that according to Moses the world was created in merely six days, and the deity took a nap on the seventh. “Moses shall have been a fool!” ranted the King. This scene occurred early, however, and aimed to underscore the King’s belief in his own cultural, political, and sectarian superiority. The musical considered a more precise question: Is cultural relativism a tenable position, or not?

The performance was didactic because, in some nebulous sense, both lead characters eventually come to recognize some of their own cultural limitations. The King’s unusual strictness notwithstanding, his defined belief in monarchy is purely conventional; like Buddhism, it is likely long-standing Siamese custom. In this sense, when Phillips’s King adamantly proclaims to Anna that “King need no one”, he is simply defending his own title, and his nation’s government, and Siam’s custom with reference to women. Though used to ordering others about, he actually takes Anna’s advice, a form of damage control, lest he be deemed a “barbarian” by the deleterious British Empire. As for the heroine, Anna, she too recognized her own limitation: she acceded to the King’s concubines that her English hoop-skirt was only Western custom, and largely metaphorical at that. Before, she objected to the Siamese customs toward women and thought herself a servant. Ultimately though, she accepted the King’s ring as well as a house next to the palace, not a suite inside it.

The subplot, which involved the dispirited, star-crossed concubine-slave Tuptim (Diane Phelan), was either overshadowed by the main plot or simply not given enough directorial attention. That said, the second act also included just nine songs, and the dramatic and thematic emphases were placed on the subplot, as commentary on the main plot. The Shakespearean play-within-the-play, an idiosyncratic but grandly performed take on Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin, took the limelight in the second act. It may have overtaken Phillips’ few regal moments. Its choreography was most exemplary, with all varieties of movement and showy pageantry, most especially the rather elegant ballet routine by Eliza (Peng-Yu Chen). Costumes were majestic and singular. This material bit of pomp and circumstance was lengthy, only slightly overdone, but may have competed with the Pope’s flamboyant, ritualistic 2008 visit to Yankee Stadium.

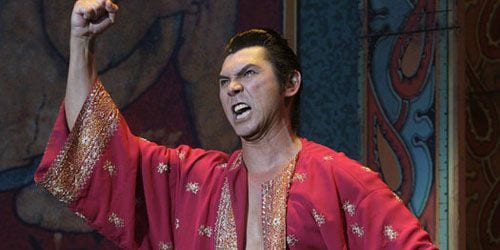

The King of Siam is of course a character type, the fearsome Asian autocrat. But tonight he was no reductive Kim Jong Il sort. Lou Diamond Phillips confidently managed to proffer complexity and subtlety to the role. A Tony Award nominee for his 1996 Broadway rendition, Phillips has performed this role for over a decade and, in my estimation, he has mastered it. He combined La Bamba vulnerability alongside a certain Stand and Deliver effortless, punkish machismo. He donned roughly ten forms of attire, the best of which being his opening monarchical gold robe.

As for Jones, in the role of Anna, a few of her scenes were not particularly notable. Jones appeared not entirely into the role, though admittedly this rendition privileges the King (Phillips). Her sobbing seemed incredible and forced; her recitation of a few lines was not fully enunciated. However, her independent-minded demand to both confront and defend the King was most persuasive, and many of her songs were excellently sung. Her best scene entailed her defiant, polished rendition of “Shall I Tell You What I Think of You?” during which she tore off her hoop-skirt to reveal slacks underneath; a pure emblem, this scene commented on Anna’s own mistreatment by the King, but also her mistreatment due to English convention. The King and I remains just as relevant today as it was when first performed in 1951 at St. James Theatre.

* * *

Starlight Theatre is a private 501(c)(3) non-profit organization, where performing arts share center stage with education.