October 2010 was a record-breaking month in Mexico: there were 359 recorded homicides. The murder rate has increased at an unprecedented rate since Felipe Calderón took power in 2006, presiding over a seemingly never-ending war between two narco-trafficking cartels. In 2007, Ciudad Juárez — where much of the violence is concentrated — recorded 307 murders, the highest figure in the city’s 348-year history. In 2008 the figure was 1,623 — over five-times the 2007 figure — rising again to 2,754 in 2009 and 3,111 in 2010.

Amongst the bloodshed fly accusations of corruption at the highest levels of the police force, the army and the government. Journalists have been killed. Concerns over firearm laws and immigration in southern states of the USA have grown. And yet the violence shows no sign of abatement. No wonder there is a $250,000 bounty on the head of the eponymous sicario, who believes he has been chosen by God to educate others about the lengths to which the Juárez and Sinaloa cartels will go to gain control of the plaza.

This ‘autobiography’, edited by journalist Charles Bowden and translator Molly Molloy, is adapted from the documentary El Sicario: Room 164. Ostensibly a lightly edited monologue, the book is divided into two sections — the sicario’s personal story and his wider view of the organisation of the cartels — prefaced by contextual introductions from Bowden and Molloy. At first this seems a lazy way to structure the book. There’s no journalistic insight; there are no ‘hard facts’; no names are dropped. After an uneventful account of his childhood, however, it becomes clear that the sicario is an energetic and entertaining narrator.

As a teenager, the sicario drives deliveries of cocaine over the border to El Paso. His naivety is abused by a drug cartel patron who offers cash, women and status in exchange for criminal acts. Rejected by his family, the sicario enters the police academy where he learns the skills and tactics he will need to become an assassin for the cartel. From the beginning corruption is rife. The sicario fulfils none of the entry requirements: to be 18; to have a draft card; to be married; to be clean from drugs. The head of the police academy picks this up. The sicario tells him, “the person who sent me here to you said that you were going to accept me without any papers. You want me to call him?”

Despite his horrific acts, the sicario is adamant that the ethical code which once governed the activities of the cartels has slipped. Previously, woman and children were off limits; now they are targets. Journalists were threatened; now they are killed. The sicario also bemoans the death of Jose Luis Santiago Vasconcelos, an assistant prosecutor in the federal attorney general’s office. Vasconcelos — one of the ‘good guys’ — was well-known for excavating dozens of mass graves containing victims of the cartel’s aggression. His death in an ‘accidental’ plane crash is the last in a long line of harbingers leading the sicario to God. Whether we believe his sins can be forgiven, the sicario’s conviction is strong.

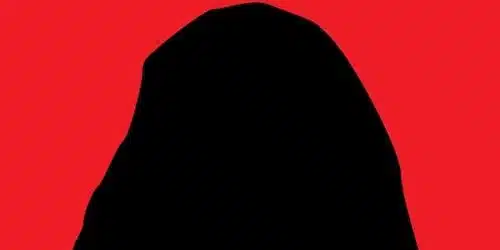

Much of this will be familiar to anyone abreast of the sporadic dispatches from Mexico (or anyone who has ever watched a gangster movie). Bowden and Molloy’s book is limited simply because, despite the insight into the reach of the cartels, there’s no record of who is involved and how. Relying on one source is problematic for all sorts of reasons. Here, the sicario is presented as an almost mythical figure. Donning a black veil while being interviewed hides the sicario’s face. Nothing more. Yet, “With his head covered, the sicario enters a state of grace, as if talking to another person inside himself … he looks like an ancient killer.”

It may say more about the escalation of terror in Mexico than Bowden and Molloy’s investigative journalism, but El Sicario neither repulses nor surprises. “Living with Hitmen”, a recent documentary from Channel 4’s Unreported World series, does a far better job of conveying the impossibility of everyday life in Mexico; no yearning for the old days, no trite religious conversion, no veil. Just good journalism.