I was ushered into the interview room to meet Michael Fassbender right on the heels of my 30-minute interview with David Cronenberg. Both men had been busy the whole day doing press for A Dangerous Method. “Wasn’t he lovely?” asked Fassbender of Cronenberg. “Yes, certainly,” I replied, nervously unpacking my recording device and setting up for the interview.

Fassbender exudes coolness. Dressed in a droopy-necked white t-shirt and jeans, he’s every bit as handsome and charming as I expected. He speaks in a fast yet intimate way, almost always smiling, and frequently smoking throughout our 20 minutes together. He immediately offered me one of his Camel Lights and began telling me about working with Cronenberg and co-actor Viggo Mortensen.

“Cronenberg’s so fiercely intelligent, no? But people maybe don’t know that he’s also got this wonderful, dry sense of humor. Of course the work was serious with this film, but there were moments we all had a good laugh on set. Viggo too—especially Viggo. He’s hilarious.” I asked him to give me an example.

“Well, you know the scenes between Freud and Jung in Freud’s home office? That space was amazing, full of all these set details which tried to approximate Freud’s actual office. It’s all wood and cigars, you know? While we were shooting this one scene, where Freud’s sitting behind his desk and I’m sitting right in front of him, and we’re having this really deep conversation which turns out to last like 13 hours or something.

And in between takes—at first I don’t notice—Viggo keeps pushing these penises, no, what do you call them? Phalluses? Freud’s desk had all of these little statutes and things, and some of them were phallus sculptures from different cultures around the world. And Viggo kept pushing them towards my end of the desk. I didn’t notice at first until I looked down and saw them all, inching ever-forward, with Viggo smirking, really a prankster, dressed up as Freud. It was surreal!”

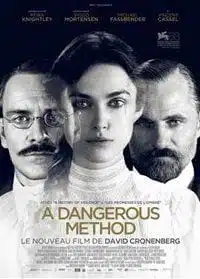

A Dangerous Method is a serious film, but it’s not without its few moments of humor, which mostly do in fact center on Freud. Mortensen’s Freud plays a kind of Oedipal third, mediating and intervening in the passionate relationship which develops between Fassbender’s Carl Jung and Keira Knightly’s Sabina Spielrein. While Mortensen’s Freud comes in and out of the story, the film could be said to center on Jung and his personal dramas, as he negotiates his marriage, his professional life and his unconscious desires throughout the dramatic action of the story. Fassbender’s performance is controlled, like the character, but the audience can always see the tensions and torsions gnawing away at Jung, displayed in Fassbender’s face and movements.

The film follows Jung’s discovery of his own sexual proclivities, charting the development of “the talking cure” as a kind of verboten sexual healing between Jung and Spielrein. While it’s ostensibly Spielrein who is the subject of psychoanalytic therapy in the film, Fassbender’s Jung is also voyaging toward self-discovery. And perhaps because this is a Cronenberg film, the apotheosis of Jung’s journey doesn’t bring self-actualization or closure.

In the final scene between Spielrein and Jung, at the edge of the water at Jung’s posh estate, he describes a recent nightmare (premonition?) of blood washing over Europe. His face is full of dread. This is a far cry from the centered, buttoned-up, ambitious doctor we meet at the beginning of the film. And it’s one of many surprising character transformations in a film full of sharp revelations about its principle characters—Freud, Jung, Spielrein—and its principle topics—psychoanalysis and central Europe on the eve of World War One.

Right before the official interview began, a spare battery for my recording device falls out of my bag and rolls towards Fassbender. Handing it back to me, he jokes, “Let’s hope the recording device doesn’t go kaputt!” “Why would you even joke about that?” I retort. “You’re right. Now that I’ve put that out into the universe…”

His joke turned out to be a Jungian premonition: 11 minutes into our 15 minute discussion, my device ran out of memory space and stopped recording. I noticed only when we finish, as I looked down and cursed the little red light. Fassbender, remembering his earlier joke, consoled me: “You see? There might be something to this Jungian stuff! Maybe my joke was me repressing my mystical vision of the near-future!”

His clarvoyant powers aside, Fassbender could rightly be called the up-and-coming star actor. In his brief career, he has worked with world-famous auteurs like Quentin Tarintino and, in his next film, Ridley Scott. In his best-seen film, X-Men: First-Class he played Magneto. Below, we discuss his role as Jung, the strategies he undertook in playing him, and the dilemmas of love and life Jung’s story animates.

As a person with a weird last name that gets messed up often, I have to ask: do people ever call you Fassbinder?

Of course! But with my name, there were plenty worse connotations than that, trust me. (Laughs) It doesn’t bother me in the slightest. When I was going in for some auditions, I may have said I was related to a certain Rainer Werner, sure…

A second cousin?

Yeah, exactly! You know, and when the time was right… Ha! But that doesn’t bother me, ’cause I got so much… “Slowbender”, you know? You can imagine all the ways to go with that name. So I don’t really care what people call me. But you know, I’m so bad with peoples’ names anyway that I don’t put much weight in it anyway. I always remember faces, but I’m pretty bad with names—even people I’ve gone to school with.

That’s what Facebook’s for.

Yeah, I’m not a member of that either. But when I get a brainfart—what’s the name, what’s the name? — then it shuts down. Boom. And then I’m in the shit! (Laughs)

Alright, well let’s get in the shit and talk about A Dangerous Method.

Of course!

Your portrayal of Herr Jung was fascinating to watch. It displayed a bold dramatic character ar, c as we watch Jung encounter himself through his relationships with Sabina, with his wife Emma, with Freud—please tell us about playing Jung and about the challenges you had inhabiting him.

I’m glad you picked up on that, because at the beginning I wanted to represent somebody who’s ambitious. You know, somebody who’s starting off and feels like they have everything to prove. And I wanted a very ambitious young man to be present from the beginning. And then he goes to meet Freud, his idol, and it’s the classic thing of meeting your idol—master and pupil—and when it gets to a certain point the pupil has to disengage from the master and goes his own way, to follow his own beliefs.

So it was a very interesting series of transitions the character goes through. First of all, he’s looking for recognition and acknowledgment of his point of view about philosophy and psychoanalysis, which he gets. And that gives him confidence to go the way he’s going. And then you have somebody who departs into this other area. And when we finish with him, he’s about to go into his breakdown, which actually happened just before World War One. That was when he weirdly prophesized what was going to happen in Europe.

Right, that’s where the film ends.

And then comes the Red Book, which is this… nuts, sort of beautiful piece of literature and illustration.

Did you get that book in your research for the character?

Yeah, even though it maybe wasn’t necessary, I wanted to see what happened to this guy’s life after we leave him in the story. So I went into the bookshop to get it, thinking it was like a diary or something. And so I asked, “do you have the Red Book?” and they pulled out this massive thing. I was like, “Holy shit! How am I to carry this on my motorcycle?” (Laughs)

Now, in terms of embodying this man, and this is true for any of the films I’ve been in or the stories I help tell, I’m just spending a lot of time with the script. I read biographies of Jung. I watched lots of videos of him on YouTube, where you can see him as an old man. There I grasped little shadow movements and physicalities which then could be perhaps adopted.

Crucial is to pay attention to the society the character’s a part of at the time—this is a period piece. Language is very much a weapon back then. To be eloquent and well-spoken at the time was essential, otherwise one couldn’t survive in this kind of academic environment. And so I had to get a grasp of this. And of course a grasp on Christopher’s script, which has a beautiful rhythm to it. It’s a muscle, so I needed to work really hard on that. And only then could I work on the physicality of the character.

OK, how do I embody him? How does he move? Well, he’s a doctor; he’s a scientist; he is somebody who is very much involved in the brain. So everything in his physicality should manifest itself that way. And also, you know, there’s the fact that Jung liked to eat. So I incorporated those things that help fill him out, and then I related to myself of course. Learning to be him meant trying to understand him as opposed to judging him. Trying to find relevant things in myself.

I’ll always write a list of characteristics down. And I go, “OK, this one, I’ve got that, but this one, not so much so I need to work on that. Like: I need to work on the intelligence of the character.” I mean, he’s far more advanced than I am! But essentially, you know, I read the script 250 times.

For real?

Totally. So that was certainly the basis for the rest.

I was really intrigued by the several scenes between Otto and Jung. On the one hand, Otto seemed to almost be corrupting Jung, but then I saw you playing Jung as somehow requesting permission from him to be naughty. I wonder if you could talk about these scenes and why they’re so crucial to Jung’s character.

MIn the way that we told the story here, Otto does come at a crucial point. Jung is going to tip over the edge with Sabina. He has serious feelings for her at this point. So it’s like how you said; he’s looking for somebody to say that it’s okay. And that’s exactly what Otto does. Yet, he’s a very smart individual, and the way that Christopher dealt with that in the script, to make him aware that he’s being seduced, to make him aware that Otto’s a dangerous influence on him… Otto is a seductive dude.

Jung’s used to Freud, who’s appreciative of his thought but skeptical of his beliefs. Freud is so…contained, if you like. And so is Jung. It’s about keeping everything in order. But we see him at the point where the lid’s going to fly off and he’s going to let it rip. he introduction of Otto in the story at this point is clever because Jung’s already there being tempted.

And, you know, Otto makes sense! I mean, I don’t believe in that sort of existence. I don’t think you can live that way—well, obviously, he died a young man in 1919 just after the war of starvation and likely the abuse he put his body through. Also the way he treats people, because I do think that matters. It echoes through the universe, and it can come back and play its part in your life again, you know? But he makes some kind of sense, doesn’t he?

So, switching gears: another key aspect of Jung’s character in the film is his split between his public, scientist self and his private, husband self. The dynamics between Jung and Sabina and Jung and his wife Emma are wrapped up in the ways he thinks of his roles, as scientist and doctor, or as father and husband. Did playing this character teach you anything about marriage and fidelity?

Well, I think it’s something that he clearly is trying to justify to himself, you know? He did go on to have an affair with Toni Wolff, and she actually, as far as I know, lived in the same house as his wife. And that’s the sort of area where you think to yourself, wow. It was because of his wife and her wealth that he was able to live the way he did. That he could go into psychoanalysis, and, you know…

But not just her material support, but the license she gives him…

No, right, exactly. But there’s no question that he would ever be in any financial difficulty. And this for a man who came from a fairly frugal family and a deep religious background. So that’s the ambiguity of the character, but also people in general.

These are the dilemmas people face, the battles they face in their lives all over the world. You’re supposed to have fidelity, to have a monogamous relationship, but then, in reality, how does that play itself out? It’s not like I come away with any particular wisdom I can impart on about marriage or fidelity or whatever, but playing this character, and just seeing the film, it really complicates the basic notions like love, sex and commitment that people everywhere grapple with…

* * *

…and that’s where my recording ceases, cutting the final part of his reply short.

We ended by talking about Sabina Spielrein and Keira Knightly’s powerful performance. He described working with her (“so commanding and gifted!”) and navigating the intimacy of the kinky scenes. To my question about the potential awkwardness of shooting sex scenes, he scoffed, waved his hand and assured me that, when working with professionals, it’s not so bad. And then suddenly, time was up.

Considering his body of work, this adroit performance as Carl Jung likely won’t be regarded as a turning point in his career so much as another fine exhibit of Fassbender’s skill and talent. Maybe that’s a premonition of things to come.