Though I remember happily leafing through Chicken Soup with Rice as a kid, and I certainly owned my fair share of Where the Wild Things Are editions, my favorite Maurice Sendak memory is ultimately of someone else’s reading experience.

From an author’s perspective, I must have been a pretty easy conquest of a child — a natural bookworm who’d throw herself at anything with pages, an eager student. I was easy to engage. But the amazing thing about Sendak is that he got to the reluctant students, too — the ones who were angry about rules and their moms and the sorry state of the real world. At least, he spoke to one of my students like that.

The memory begins in fall of 2009. I was working as a middle school teacher’s assistant — my first job after graduation, but hardly the one I wanted. The pay was lousy and the commute was long. The gig barely required the education I’d spent years and years accumulating. Toss in a windowless room filled with moody pre-adolescents, add a dash of my own extended adolescence, and we had quite the recipe for misery.

Thankfully, my cooperating teacher made the class setting lively and fun, lining the walls with books and cute little comic sans-typed aphorisms, so, no, we weren’t completely miserable. Still, it was a very “middle school” experience. The kids, being pre-teens, were a wild and unpredictable mix of defiance, kindness, humor, embarrassment, wisdom, and (their favorite word) drama.

That is, except for one student. For anonymity’s sake, I’ll just say that this student wasn’t defiant or dramatic or (from what I could initially tell) particularly curious. He was bored. He was tired. If we were engaging him with lessons, he definitely wasn’t letting on; instead, he opted to use his pen-marked desk as a pillow during class.

He was only 11, but there was a sort of world-weariness about him that I was just beginning to recognize as a 20-something postgrad. Life was tough. My youthful idealism was wearing as thin as the tires on my overused car. And this kid, he had already seen too much. He’d drift off during class, preferring the forest of his mind to whatever we were dishing out in class. If I got him to finish a basic worksheet, I considered the day a success.

That’s why I was shocked one day when he entered the classroom with uncharacteristic verve, arguing with some peers, “You guys are INSANE. That movie? It was AMAZING.”

“No way,” a classmate countered, “It was totally boring, and so was the book.”

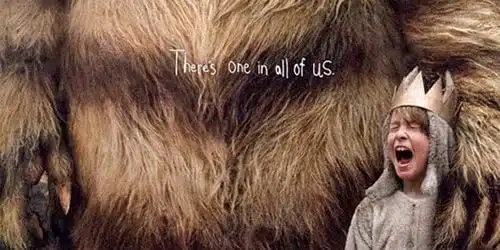

The movie in question was, of course, Where the Wild Things Are, the Spike Joneze-directed adaptation of Maurice Sendak’s indelible children’s book. It was one thing to say Joneze’s movie was “boring”, but it was quite another to dis the classic children’s story. My heretofore disengaged student then began to passionately list the great aspects of the book: Max’s awesome wolf suit, his angry defiance of his mother, the creepily detailed pictures of monsters that famously “roared their terrible roars and gnashed their terrible teeth and rolled their terrible eyes.” There were moments he liked in the movie, too, like the scene in which movie-Max stomped his snowy boots all over his sister’s bedroom in anger like a pained wild thing himself.

The movie also had the added benefits of nostalgia, reminding him of the elementary school days he missed, back when teachers read picture books aloud to him with feeling. It seemed like the book reminded him of his former innocence, even as it spoke to his inner fierceness.

I don’t know if it was the magic of nostalgia or the lure of unrequired reading, but talking about Where the Wild Things Are lit a fire in this student that I’d never seen in him before. I would see it in fits and starts throughout the school year, like when we read Jerry Spinelli’s Maniac Magee aloud in the spring, and I felt silly to have ever doubted his curiosity. He probably taught me more than I taught him that year.

As he opened up and engaged more in class, I saw that, while books obviously don’t solve all the world’s ills or change anyone’s life from start to finish, they can help us cope. They motivate, they wake people up, they can make a lonely reader feel less alone.

Maurice Sendak knew how to speak to the student with his head on his desk in a way that resonated. He used words and pictures to move the seemingly unmovable, and he did it on such a large scale, for so many children and adults, that it’s clear to see he’s made a lasting, positive impact on the world he left behind on 8 May 2012. He may not always have been happy, nice, or even “sane” (as The Guardian suggests in “Maurice Sendak: ‘I refuse to lie to children'”), but he was a maker of inarguable value, and the world surely benefited from his genius. I know at least one boy who did.