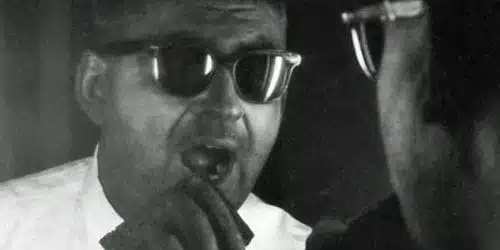

“What is it like to be the Other? A few, very few, thoughtful heroic whites… have at one time or another considered the idea. It was one man who actually followed through. John Howard Griffin, a white Texan, thought the unthinkable and did the undoable: he became a black man.”

— Studs Terkel, from the Foreword

One of the several perils of being a critic is that, with the best intentions in the world, you occasionally find yourself in over your head. Like, for instance, if you’re a WASP-y middle-class Canadian woman and you find yourself staring at a review copy of Black Like Me, in the 50th anniversary edition, no less. Not that this is why this review takes place so late into its 51st year, but the recent Trayvon Martin debacle did not exactly boost my confidence in my ability to pontificate on John Howard Griffin’s iconic take on racism in America, circa 1959.

Griffin takes his cues from the simplest of basic human compassion and curiosity. Regardless of your stance on his conclusions, viewing his experiment 50+ years later, there’s seemingly no way to dismiss the man either as hopelessly naïve or a cynical publicity-seeker. Extraordinarily enough, the book reads exactly as though the initial impetus was neither more nor less than claimed (and surrounding materials corroborate): an intelligent, thoughtful man’s concern that scholarly studies of African-American sociology were not providing the full story, given that black people’s answers to white researchers were so obviously — understandably — not to be trusted, and his desire to see how best he could rectify that situation.

Why it then became necessary – especially given Griffin’s physical frailty — to literally darken his skin, through a combination of drugs bolstered by tanning treatments, and cut himself adrift from not only outward identity but inward self (which on its own becomes an interesting running meditation), is one of the first hurdles to a serious reading of his experiences 50+years later. The subsequent lighthearted co-opting of the idea by the current pop-culture mainstream is based not so much around disrespect as incredulity, at what seems like such a wholly – unnecessarily — outlandish stunt. After all, to all appearances African-Americans have been, within the memory of multiple generations now, not only free to tell their stories but to celebrate their culture — to the extent where many whites now enthusiastically identify with their ‘outsider’ status… and others begin to openly resent the notion that the black community needs any assistance at all to put itself forward.

Fifty-plus years on, inevitably, a sort of detachment has been lent to the details of the civil rights movement: the ‘back of the bus’ and separate drinking fountains and school riots and even the Rev. King’s “I Have a Dream…” speech increasingly act as shorthand for that difficult era. At this period in time, it’s faintly bemusing that the re-release of Black Like Me should should mirror so closely the familiar media touchstones of the civil rights movement, that it should make such obvious arguments and come to such now familiar conclusions; to the point where a reader can’t help but begin wondering, especially at the more lurid bits, if Griffin hadn’t made at least some of it up, or at least embellished it for dramatic effect. But alas, he hadn’t.

Those clichés didn’t exist back when Griffin was writing. Back in his time, this was all still a work in progress, and the status of the ‘Negro’, in social and scientific terms, was still subject to large grey areas. Many of which, of course seem outrageous today, but at the time, they loomed large enough that an attempt to disprove them, to get the real picture, was no easy matter. This is vividly illustrated by the sheer amount of space given to pointing out the circular illogic of systematically stripping a people of their dignity and then using their anger as an argument for further ill-treatment.

It also makes for an interesting basic springboard for the ever more complex questions around black self-identity vs. assimilation into the dominant culture. Really, the grey areas haven’t so much been filled in as replaced with new ones; anyone who has grumbled over the black community’s failure to ‘pull themselves up from the ghetto’ may want to review the author’s post-experiment epilogue, which vividly describes not only the attempt by a now-fully-engaged Griffin and fellow-travellers (including radical comic Dick Gregory) to consolidate the basic gains of the civil rights movement, but the beginnings of the ever-more-complicated African-American struggle for control of radically re-imagined destiny.

This is where it’s apparent that Black Like Me is not only still a relevant but an immensely valuable read, in these times. At the core, it’s not about clichés of black or white, from whatever perspective, but about all people, and how they perceive and relate to one another. This is not by any means a simplistic book, nor one populated with strawmen of either colour; still, the quiet sincerity of Griffin’s odyssey bypasses the extremes of rhetoric — and further, explains clearly and cogently why none of them suit the case, because they are not at the heart of the matter. His passion was to know how otherwise eminently ordinary Americans really lived, thought, and coped under the constant pressure of being considered second-class citizens at (very) best, and subhuman at worst. Black Like Me is a compassionate logical rebuttal to irrational hatred, and thus immensely powerful.

This is a book that discusses, quite simply, man’s inhumanity to man – man’s denial of humanity to man — on a sort of ground-floor instinctual level that not only compels the reader to respond in kind, but further insists they think about their response. It’s one thing to contemplate in the abstract the grotesque unfairness of not being able to drink from a fountain on the basis of skin colour – quite another to have it narrated by an ordinary man of one’s own race (assuming the reader is white, of course), forced to wander about thirsty and tired because a paper cup of water and a park bench, so easily accessible under one’s own circumstance, on the other side of that incredibly flimsy barrier might as well have been on Mars.

When I read the first chapter, years ago as an earnest teenager, I was struck by Griffin’s adventures hitch-hiking with good ol’boy truckers, who were just sort of amiably avid, if you will, to verify rumours of the Negro’s sexual prowess – amiably, that is, until Griffin refuses to gratify their curiosity. The only response my young mind could possibly have was to put the book down and think about other things, at least for awhile. I felt soul-bruised. And I felt that way again, on this reread. Clearly, that is at least part of what Griffin hoped to invoke in his readers.