If we all disappeared tomorrow, vanished in some cosmic or religious holocaust, the world we’d leave behind would be a vast puzzle. If any intelligent life in the universe should stumble upon our empty world its citizens would marvel at the beautiful mountains, forests, deserts and oceans, but they’d scratch their bulbous heads at all the rest: plastic bags, packs of firecrackers, pornography, salt and vinegar chips, the smiley face design, and advertisements everywhere.

What sort of picture would emerge from the collision of these disparate visions, the beautiful and grotesque, the high and the low? How would these hypothetical wanderers interpret a world of such contrasts? Better yet, how do we? We’re still here and we struggle with the same question. Art is key, of course, if only because it’s so essential to who we are. In every medium art shows us our highest ideals and our darkest nightmares, and this gap is bridged by everything from sculpture to velvet painting. Some artists, however, take their inspiration from the incidental, lowercase art we encounter every day.

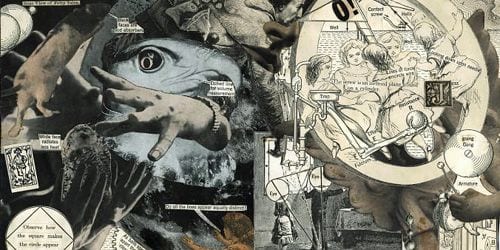

The artist Jess was born Burgess Collins in California in 1923. He trained as a chemist and worked on projects relating to the development of nuclear weapons. He was so disillusioned by this work he turned his back on science and embraced art. His work carries something of his previous career with it, however. Jess’ collage and paste-ups create ideas, forms, and landscapes from the clipped molecules of media ephemera. Advertisements, comic strips, poems, and pornography become new compounds in his hands. Combining various chemicals in a lab might result in an unstable compound, and on paper Jess’ work is no less explosive.

O! Tricky Cad and Other Jessoterica collects an astonishing amount of work, a dense collection of word and image which presents something new upon each viewing. “Tricky Cad” is a collection of altered Dick Tracy comic strips, the words repositioned to create a surrealist detective story. The strips easily recognizable elements give the viewer the sense, at first, that maybe things are as simple as they appear, but reading the characters’ jumbled dialogue quickly dispels that notion. Reading these perversions of the comic strip, one is struck by what actually remains from the original: attitude and absurdity, the pillars of a great detective story.

The words change, but the images remain largely unchanged. The tension between word and image, as in all of Jess’ work, creates a dizzying effect, the reader stumbling for sense. The brain can’t fill in the holes with meaning. Every word is a struggle. Jess creates the same effect with “Nance”, a frontier comic strip altered to become a parody of ’50s American masculinity. Characters are pasted into intimate embraces and compromising positions. It’s jarring because of the repressed era in which these strips were created, but it’s also very funny.

“O!”, a pamphlet included within the book in an envelope, is a mini-comic, chap book, zine, and art book published in 1960. Long segments of poems and quotes form the text, and it all washes in and out of black and white images of old technical drawings, bits of sheet music, and other images, layer upon layer of them. Poet Robert Duncan, Jess’ partner for over 50 years, writes in “O!”’s introduction, “Absolutely no part here is originally the artist’s. What he has achieve is totally his, but in every detail derivative.” This comment seems obvious enough given the nature of the work, but it draws our attention not just to Jess’ end result, but how the pieces come together. We don’t need the “why” of Jess’ motivation to understand his intent, but looking at the how, really paying attention to the intersection of images and words on the page, opens up the work to the viewer no matter the medium.

Still, Jess’ work can be overwhelming, demanding, the viewer feeling total immersion in a given piece. His word collages create the effect of speeding down a city street trying to read every word as it flies past. Words and letters are shapes, and Jess creates beautiful typographical arrangements, but the impulse to read remains even in the absence of obvious meaning. These collages become an interaction between the shapes of the letters and the sounds they make. They are poetry.

Playing with language also figures in 1954’s “Maxims for Minions”, a title which is surely also the name of a long lost punk rock record. Meaning is a little less subjective with these maxims: “Love cankers all; honour thy feather and martyr; bards of a father defrock one another.” Jess appropriates the form and shape of well known sayings and plays “Telephone” with them. Coupled with their accompanying collage, these maxims read like wisdom from some alternate reality, one which Jess understood as well as he did our own.