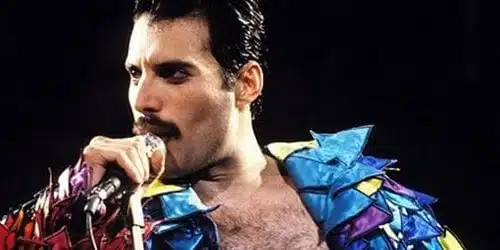

Queen’s Freddie Mercury was never “just a singer in a rock ‘n roll band”, a la the Moody Blues classic. He was a force of nature. In concert, he pranced about the stage like a deranged primo ballerina, his grand vocalizing soared beyond the back row, and you never knew what he’d be wearing when he made his entrance. In Rhys Thomas’ penetrating new documentary, Freddie Mercury – The Great Pretender, Mercury himself sums it up best, proclaiming “the bigger, the better… in everything.” He lived large, and pop culture was all the better for it.

This documentary focuses primarily on Mercury’s solo material and private life, as there already exists ample information about Queen. Mercury was hardly your typical British rock frontman. For one thing, Farrokh Bulsara – his birth name — was born in the colonies, storied Zanzibar, to be precise, and educated in Indian boarding schools, where he sang in the choir. Later he attended art school in London, a common listing on the resumes of numerous Britpop artists. Mercury’s singular vocal delivery and flamboyant mannerisms evoked Broadway, Las Vegas revues, and opera. In his work with Queen, he frequently incorporated earlier genres and sensibilities into a guitar-driven rock architecture. His inimitable style brought him international fame with the renowned rock quartet, and by the early ’80s, he was among the most celebrated performers in the world. The band’s set at 1985’s Band-Aid charity spectacular – led by Mercury’s messianic showmanship – confirmed this.

At a crossroads, Queen took a break in the mid-’80s, and Mercury launched a solo career, hardly a surprising move. His erstwhile bandmates were surprised and a bit miffed, however, at the largesse of his contract with CBS Records, which exceeded theirs. His debut single, the sadly prescient “Love Kills”, appeared in Giorgio Moroder’s curious re-release of Fritz Lang’s landmark Metropolis, and was followed by the LP Mr. Bad Guy. Musically, it differed little from recent Queen recordings, yet it failed to even approach the Top 100 Albums chart in the States, despite strong sales in their native UK and some European territories.

Two years later, Mercury would unveil his cover of The Platters’ chestnut “The Great Pretender”, which would become his best-known solo recording and, ultimately, an epitaphic nickname. The song was supported by an elegiac and satirical video which presented clips of his countless stage personas from his Queen years, including his controversial drag diva which angered some fans at the Rock in Rio Festival in the early ’80s.

Freddie Mercury – The Great Pretender moves at a swift pace, clocking in at under 90 minutes, and features lots of interview footage of its subject. Mercury took his work quite seriously, but he was also a clown and a tease, whether giggling over German profanities during his stay in Munich or schmoozing at a debauched discotheque soiree. Thomas also excels at utilizing Mercury’s tunes to tell the triumphant yet finally tragic tale of his life.

Of course, Mercury passed in 1991 from AIDS-related complications, and his death – sudden to most fans – dredges up prickly questions about identity, privacy, sexual promiscuity, and homophobia. A ravenous performer, audience feedback clearly was a drug for Mercury, and sometimes the “audience” was just another man sharing his bed. Perhaps Queen’s “I Want It All” comes to mind while hearing him confess to being “extremely promiscuous” in his early ’80s heyday, when he immersed himself in New York and Munich’s hedonistic gay nightlife, the worst time to be devil-may-care in such a milieu.

I recall when Mercury acknowledged his HIV+ status back in 1991, a mere day before he expired. His openness regarding sexual orientation was more slippery. It seems that it was an open secret; like Rock Hudson, friends and industry insiders knew, but you’d never find any confirmation in the press. Mercury was an avowed bisexual, though, like Elton John, he later chose an exclusively homosexual lifestyle, and we hear from his now-deceased partner, Jim Hutton, who speaks candidly about their relationship. It seems that Freddie adored him.

Queen initially rose to fame blending opera with arena metal, traditionally an insufferably macho corner of the rock universe, but Mercury also loved funk and rhythm-and-blues, and he led (dragged?) the group in that direction with The Game(1980) – who can forget the brawny funk workout “Another One Bites the Dust”? – and the highly electronic Hot Space (1982), which took them deeper still down that particular rabbit hole, alienating many heterosexual hard rock-craving fans, especially in the US. They never recorded a disco tune, because, prior to The Game, white male rock fans, again mostly in America, had hounded disco back into the clubs from which it sprang in the early ’70s.

Those same fans largely rejected Hot Space, and the band’s stateside popularity waned thereafter. Nevertheless, Mercury was determined to explore his eclectic tastes, and danced with the Royal Ballet in 1979, perhaps a signal that even greater artistic transformation was on the horizon.

Prompting those changes, to some extent, was his admiration of – and friendship with – another superstar of mysterious sexuality: the King of Pop, Michael Jackson. His unreleased duet with Michael, “There Must Be More to Life Than This”, gets some play in the documentary, and we’re told that the ever-eccentric Jackson’s llama accompanied him to the studio. We can only wonder what an album of duets with this pair might have sounded like. Mercury’s solo rendition of the tune appears on Mr. Bad Guy.

Apart from his Queen oeuvre, I suspect the man who wrote “Bohemian Rhapsody” would be most proud of his sophomore solo project Barcelona (1988), a collection of duets with noted Spanish opera soprano Montserrat Caballe. Mercury was approached to record a song for the 1992 Summer Olympics in the eponymous city, and though CBS declined to be involved, he went ahead, and the final result was a full-length album, which succeeded in finding an audience, especially after its 1992 posthumous re-release. Not everyone was thrilled with Barcelona, however. The imperious Luciano Pavarotti denounced it as a “dumbing-down” of opera. Still, Mercury and Caballe remained great pals until his death three years later.

Extras included in this DVD package are scant but significant. In “Freddie Mercury Goes Solo”, there’s an extended 1985 interview in which he discusses the production of his solo debut. Next, Montserrat Caballe, who already enjoys a generous amount of screen time in the doc, talks about collaborating with Mercury, and reveals that he wanted to record Phantom of the Opera with her. Finally, “Making Barcelona” details the process of creating the classical orchestration used in Barcelona. The video accessories are complemented by a six-page booklet containing the director’s essay about his lifelong interest in Mercury’s work.

Freddie Mercury was a “great pretender”. He adopted wildly disparate guises in his mesmerizing onstage performances. He harbored the secret of his devastating illness until he was almost gone. Even his nom de plume is a fanciful concoction, evoking great speed; the swift social ascent of a buck-toothed, olive-skinned lad from an ‘exotic’ land who rises, Horatio Alger-like, to white-hot global celebrity. When he sang, he invited you to “spread your wings and fly away with me”. The Great Pretender was also the real deal.