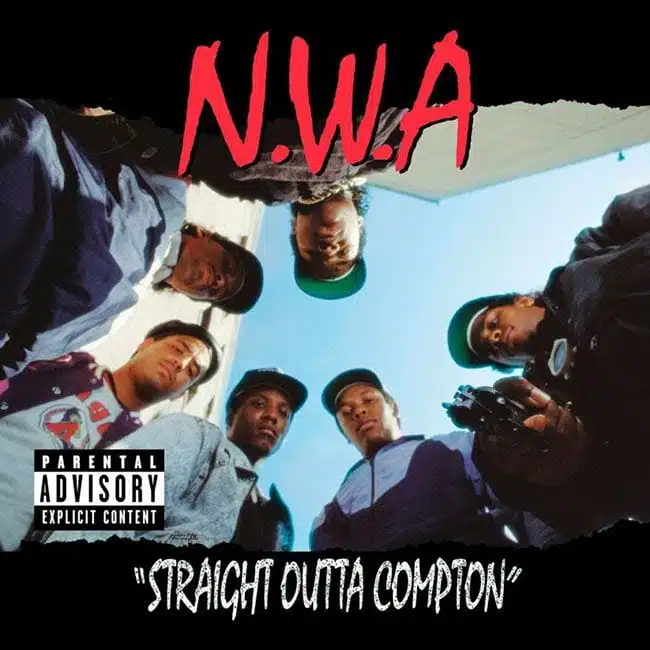

Mendelsohn: Hip-hop, Klinger, hip-hop. It’s back and now that we are out of the Great List’s Top 100 and moving further away from the canonical rock ‘n’ roll entries, I expect we will be seeing more and more hip-hop as the list progresses. This week we get to talk about the seminal hip-hop group N.W.A and their ground-breaking, gangsta-rap template-creating entry, Straight Outta Compton. N.W.A helped launch the careers of Dr. Dre (famed rapper, producer, and headphone maker), Ice Cube (famed rapper, star of several slightly profitable kid-oriented movies ,and commercial shill for a bland American light beer) and Eazy-E (famed rapper?); also there was MC Ren, Arabian Prince, and DJ Yella. Between them, they single-handedly put West Coast hip-hop on the map. Maybe more importantly, the stylized content dealing with graphic scenes of hood life, the trials and tribulations of gang activity and the socio-economic impact of living in such areas become the template for what A&R folks at many major record labels would look for and actively push upon the listening public as hip-hop started to gain more market share in the mid-1990s.

There are a myriad of different directions we could take this discussion, Klinger. But I want to know where you want to start. When you pop the cassette of this album into the deck of your drop-top, ’64 Impala, what’s the first thing that comes to your mind?

Klinger: Oddly enough, the first thing that comes to mind is college. I was a junior in college when this album first made its way into the consciousness of our circle, and it was played fairly often at certain social gatherings. Even now, after having gone 25 years (dear God) without really listening to it, I’m surprised at how much of it has stuck with me. It helps that the group featured some of the most distinctive voices in hip-hop (is it just me, or is MC Ren underrated?). For the record, I largely skimmed the surface of hip-hop in my younger days, focusing primarily on Public Enemy and De La Soul (which puts me in league with most rock critics, by the way), but this was an album that was in pretty heavy rotation among many of my friends.

Obviously, and I’m sure this has been addressed by people much more astute than I, it’s curious that Straight Outta Compton would be so fully embraced by white Midwestern college students. And maybe “embraced” isn’t exactly the right word. Of course nowadays, hip-hop is far more universal, and listening to it seems way less of a statement. So I guess I’m interested in how someone your age, who has grown up with this music in the (relative) mainstream, responds to N.W.A. Does it maintain its power?

Mendelsohn: I was never a big fan of gangsta rap, although I listened to my fair share growing up because I had some friends who were pretty big fans. To this day, I can put this record on and they can recite it word for word. It was a mainstay, a fixture in our music world, which, oddly enough, was pretty well dominated by hard rock and metal at the time. We are talking about some very white, very suburban kids who had no problem flipping back and forth between Metallica and N.W.A. It is a bit surreal to think about it now, but it was a scene I witnessed several times and never gave it much thought. The correlation, of course, is the thread of rebellion, anger, and dissonance that pulled the two disparate genres together, leaving them seamless in our pubescent mind set.

Listening to it now, I can still feel the urgency and anger backed by despondency and bleak humor that drove this record into public consciousness, but as with most albums, time and the varying career trajectories of the artists have dulled the cutting edge of the content. At the time though, I think listening to this album was a real statement of defiance for the youth of the Midwest and provided a bit of an escapist — if not voyeuristic — experience, from the relative safety of suburban sprawl. If nothing else, it was very much a window into a different world—something far and away different from all of the other windows we could have been looking through.

Klinger: Yes, I think you’ve hit on just the right point here—bleak humor. As I’ve been steeping myself in N.W.A of late, I keep coming back to the idea that there is a great deal of humor on here, but it’s mixed with a certain darkness (even beyond the constant references to shooting people). I can’t help feeling that Straight Outta Compton laid at least some of the groundwork for what rock music was to become in the 1990s. Pissed off, but not really at anything specific. Certain that external forces were keeping them down, but unable to really articulate what exactly. (OK, N.W.A did not care for the police, and as the entire world would later learn, they had a point. Still, much of their ire is cast pretty widely.)

Straight Outta Compton was criticized for glamorizing the gang lifestyle, but these songs are anything but freewheeling. So many tracks on here make it all sound downright enervating. And even when they’re rapping about sex, as in Ice Cube’s solo spotlight “I Ain’t the 1”, it’s mostly about how annoying women are with their money-wanting and so forth.

Even on their party track, “Something 2 Dance 2”, they spend a surprising amount of time complaining about wanting to leave the club. It’s all pretty funny, and it’s certainly an exciting listen, but it is pretty dreary, yes?

Mendelsohn: Dreary indeed—almost to the point of resignation in some spots, but that’s the place this record came from. N.W.A was looking for an outlet from the socio-economic decay of their neighborhood. The violence, the drugs, and the prevalence of gangs are all important but that’s not what this album is about — those things were merely the trappings as Ice Cube, Dr. Dre, MC Ren, Eazy-E, and DJ Yella tried to make sense of the world around them in some sort of existential struggle between survival and expression. They are angry (see “Fuck tha Police”, and “Straight Outta Compton”) but they also just want to be heard, or more importantly, the chance to be heard, especially coming from a traditionally voiceless segment.

Out of everything on this album, I always found Dr. Dre’s solo shot of “Express Yourself” to be the most intriguing. There is a call for originality (ironic, I suppose, considering the sample of Charles Wright’s song of the same title) and a bravado that makes me smile every time Dr. Dre puts out the call to express yourself. I think that’s the central tenet of this record: freedom of expression. Plus, I love the sample and you really get to see how influential Dr. Dre was at repurposing funk and soul to serve as the backdrop for the West Coast hip-hop movement.

Klinger: And we’ll be talking further about Dr. Dre in just a few short weeks as The Chronic clocks in. You know, years ago I was talking to a local jazz pianist, a guy named Claude Black, who’s played with so many of the all-time greats—from Donald Byrd and Fathead Newman to Aretha Franklin. I asked him about the difference between playing with West Coast guys versus East Coast, and he said a lot of had to do with the weather. He said the cold keeps people all scrunched up and tight, so they might be more direct in their playing. On the West Coast, though, they play more laid back because the weather’s so nice. That seems to be the case with hip-hop too. As forceful as it might be, there’s still an openness to the West Coast sound.

So even though there’s an undercurrent (or maybe an overcurrent) of anger to Straight Outta Compton, it seems that they also can’t help infusing it with a party-record sense of humor. The fact that they set up “Fuck tha Police” as a courtroom drama is evidence, although I question their grasp of the intricacies of the judicial system—why are they calling prosecuting attorneys up to the witness stand?

Mendelsohn: I don’t know. Possibly because after the police, it was the prosecuting attorney who was really responsible for sending so many young men up the river and hip-hop has always been used to air beefs between respective groups. Or it could be a farcical play on the ridiculousness of the judicial system. It’s complicated, man. But then, this can be a very complicated record. I think that’s really where N.W.A rise above their peers in the early hip-hop movement. In essence, they were able to distill some very different emotional strains into a head-on assault of the ears in general, and maybe more specifically, some very ingrained notions about the lives many Americans were unable to see in any meaningful manner. And if I had to give N.W.A one more bit of praise, Straight Outta Compton is one of the few great rap albums that is completely free of those dumb skit and interstitials. Wrap your funny bone around that.