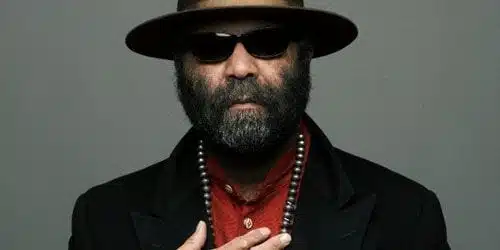

The problem with Otis Taylor has always been very simple: he puts too much stock into his not-particularly-engaging voice and not enough stock into his well-honed musicianly sense of texturing — specifically, the banjo and/or guitar playing that he gets out of either himself or whomever he’s hired for his latest album. A black man born in Chicago but raised in Denver, Taylor’s a banjo, guitar, and sometimes mandolin player who was a professional bluesman in the mid-’70s but quit for a long while and has been releasing solo records for only the last 15 years or so. Well into his 60s, he both sounds and looks like he could’ve come from anywhere in America. And he does try to show that in his performance, usually reflecting very somberly on racial disenchantment and the encroached parallels in the past that continue to bleed into the present — the kind of stuff that sometimes gets his music labelled “conscious blues.” His approach has no time for humor and very little for hooks, and what Taylor usually calls up in his best work — “My Soul’s in Louisiana”; the very eerie “Mama’s Got a Friend”; “Ten Million Slaves”, which gained some exposure through its use in Michael Mann’s film Public Enemies — is stark disillusionment, rendered perceptible not through his voice but through the arrangements.

On his latest record, Taylor tries, sort of, to address themes of Native American life and history, and the marginalized place of aboriginals in modern society. An admirable task, clearly, and one that always feels overdue whenever it comes around in art. (This goes even for a non-American like me, confronted with the ethical implications concerning Canada’s ongoing Idle No More movement.) But though I was looking forward to My World Is Gone and hoping Taylor would finally overcome some of his lyrical vagueness, I wasn’t surprised when the results ended up being, once again, much too roughly drawn for anyone’s good. A man in one song loses his horse from drinking too much. Another stops drinking after losing his lover. One man sees a rare buffalo on TV and realizes he’s never seen one in the flesh. A wealthy banker never visits the reservation from whence his ancestors come. Pretty direct stuff. If one were to be harsh, they could say “obvious,” and I swear I’m not simplifying — this is most of the detail that Taylor gives us in those songs. Thus, the commentary here is focused on broad subject, not specifics (let alone solutions).

Which means we’re left with the music to color-up the emotional intent and amp-up the consciousness — to help the songs signify. And the music is … okay. It’s okay. Probably the most conventional of Taylor’s 13 albums, My World Is Gone is usually at its best when driven by electric guitarist Mato Nanji, who gives a fine sense of the distance to and from the grand lost landscape that the words evoke. Unlike many of his colleagues in the “conscious blues” world, Nanji isn’t afraid to plunge deep into the lower end of the register and come out with visceral, crunchy feedback: his two solos in the stimulated “Lost My Horse” surge through the grit while his lines in the calmer “Blue Rain in Africa” reach for Duane Allman’s blue sky from the realities of the wide-open plain. Even when the guitar coloring doesn’t necessarily mesh with the words — Shawn Starski’s phrasings and Taylor’s humble, sunny intervals in “Gangster and Iztatoz Chauffeur” are more Ghana than South Dakota — it’s the guitar work, especially Nanji’s, that stands out immediately. Well, the guitar work as well as — get this — the muted cornet lines, which lend a transported urgency to songs like “Girl Friend’s House” or the one-chord funk of “Huckleberry Blues” and establish those songs as highlights instead of leaving them as the trifles they could’ve been.

But in a way, even the good songs just accentuate the limitations of Taylor’s own vagueness and his large-but-weathered voice. He does address specific history in a few songs, notably “Sand Creek Massacre Mourning”, which references an 1864 massacre of about 200 Cheyenne and Arapaho natives, mostly women and children, by drunken soldiers on a whim. But even with some cold, spaced-out electric guitar slides and Taylor’s own portents that “They’re coming down,” the song never connects as haunting, ominous, or even particularly mournful. On the other end of the spectrum, that same vagueness can work in a song like “Coming With Crosses”, with dusky fiddles seeping over a light drum shuffle to imply the appropriate dread. And the man does take a few moments to remind us that a lot of this stuff is still taking place in the modern world (“bank robbers working for the bank” in “Never Been to the Reservation”), even ending the record with a comparatively comfortable statement of domesticity.

Typical of Taylor’s entire approach at both its best and its worst is the aforementioned “Girl Friend’s House”. Taylor’s vocals on that song, referencing a cheating wife, are at their most mercurial, adjusting and re-adjusting over an oscillating bass line and a simple banjo plucking that’s soon joined by a rather hopeful little cornet figure that repeats for the next three minutes of the song. “Girl Friend’s House” exemplifies the subtle call to attention that Taylor earns at his most musically on-point, and it’s one of the best songs on the album. Yet when you try to take the song as anything deeper than a nice passing blues fanfare, its significance becomes more questionable and more trivial. Looking at the CD liner notes after I’d already listened to the album, I was stunned to find out that the actual “story” of “Girl Friend’s House” is as follows: “After catching his wife in bed with her girlfriend, the husband decides he wants to join in.”

Uhhhhhh……what? Re-listening, I realized that this does make sense, kind of. But when it’s accompanied by such momentous-sounding music, I’m at a loss to explain how anyone could be expected to pick up on that meaning without reading the liner notes first, because the music that the threesome sentiment is grafted to is so humorless, so dead-serious, that its lyrics ultimately seem neither here nor there. And that’s when I realized: only Otis Taylor could make a song about a threesome and make it sound like he’s about to charge the Mason-Dixon Line. And in the end, what are we supposed to take away from a record that wants to address an issue, but whose songs are so vague and/or cheerless (“Huckleberry Blues” could be about anything, even though its “actual” subject is apparently a man being stalked by a neighbor) that the most surprising thing about the content is the cornet hooks? What Taylor communicates on My World Is Gone‘s most “conscious” songs is a sober quality that we’re supposed to imbue with significance. But the faded, delicate melancholy of the actual grandeur of what the natives have lost is rarely engaged with, and when it is it’s strained and — here’s that word again — vague. Those heavily invested in the socio-political acumen of Taylor’s music should stick with songs from the man’s early, starker records. Those heavily invested in the socio-political subject regardless of art should take a more volunteerist approach.