In the quarter century since the Smiths disbanded, Johnny Marr has been content to blend into the collective protection of ensembles, staring out of the shadows of his own legacy as his recognition as a guitar genius has grown from insider insistence to well-established fact. Marr seems to have taken comfort in fading into a crowd instead of forging a singular path. When the Smiths called it quits — prompted by his own defection — Marr spent a day jamming with Sir Paul before playing a brief series of shows with another iconic group, the Pretenders.

From there, Marr joined up with his old pal Matt Johnson in The The before forming a supergroup of sorts, Electronic, with Bernard Sumner of New Order and Neil Tennant of Pet Shop Boys. During and in between all of that, Marr recorded with everyone from Kirsty MacColl to the Talking Heads to Billy Bragg — to name but a few. And, oh yeah, Marr enlisted in Modest Mouse for a bit. There was that, too, which was pretty damn cool.

Yes, Marr has been busy during the last 25 years, but he hasn’t been all that visible. Even when Marr stepped into the role of lead singer, he chose to blend in rather than stick out. Johnny Marr and the Healers was Marr’s first attempt at a solo outing, but even that was a group, the name granting him both front-role status and some degree of anonymity, couching him into the comfortable confines of a band.

That Marr would be reluctant to emerge as a solo artist from one of the most iconic bands in rock history is understandable. After all, by the tender age of 24, he was responsible for writing the music to some of indie rock’s seminal tunes: “How Soon Is Now?”, “Please, Please, Please Let Me Get What I Want”, “Back to the Old House”, “This Charming Man”, “There Is a Light that Never Goes Out”, “Stretch Out and Wait”… The list could go on for paragraphs.

To say that Marr laid the sonic blueprint for indie rock, then, is not to resort to hyperbole in any regard. You can trace his influence from the “How Soon Is Now?”-nicked guitar riff in U2’s “So Cruel” to the folk delicacy of the Sundays and Belle and Sebastian to the shimmery bravado of the Killers to just about any other indie band that has made music in the last two and a half decades. Even if they weren’t influenced by Marr, they’ll still admit his undeniable impact.

So perhaps it’s taken a full quarter century for Marr to feel that there’s enough distance between the Smiths and the present and that he could finally put out his own music as a solo artist without unfair and irrelevant comparisons to his former band.

Whatever his thinking, Marr has finally done just that — released his first album as simply Johnny Marr. No more “and the”. No more blending into pre-existing bands. No more supergroup collaborations. Just Johnny Marr. Yes, this is largely a matter of semantics, as Marr is surrounded by a band, but this is the first time Marr has put his name — and, therefore, his reputation — out front and center.

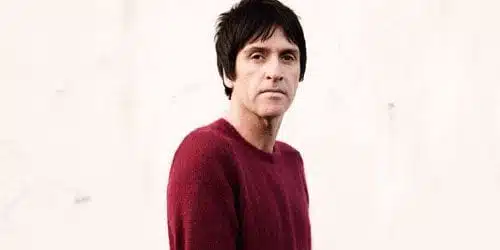

This is a bold move for someone of Marr’s stature, but on The Messenger he sounds completely confident and at ease. Even in the promotional photos for the album, Marr seems to be having a thoroughly good time, enjoying the opportunity to be the only person in the frame.

This casual confidence permeates the whole album. Whereas Marr seemed tepidly hesitant to front a band on Boomslang, the Healers sole release, he sounds emboldened on The Messenger, firing off a series of songs that sound both spontaneous and diligently crafted.

Album opener “The Right Thing Right” sets the tone for the album, featuring an insistent drumbeat that grounds the tune while Marr flies overhead with subtle slide flourishes. Noticeably, the song features no jaw-dropping guitar histrionics, just tasteful playing and a sturdy chord progression. Marr does drop into the middle of the song to deliver a Byrd-sy solo before disappearing back into the mix.

And that’s the approach Marr takes throughout the album; rather than overtly flaunting his guitar genius, he consistently serves the song rather than his own legend. When you think about it, though, that’s why Marr was an unusual guitar hero in the first place. How many memorable riffs or chord progressions of Marr’s come to mind? Tons. How many of his solos come to mind? Few. Marr has always put taste above flash, and while he flaunts more solos on The Messenger, they’re always organic.

Indeed, Marr more frequently chooses to weave subtle guitar lines throughout an entire song than construct songs around self-serving heroics. The title song, for example, features a catchy, atmospheric riff that helps introduce the song before working its way back into the verses and choruses. Angular and exotic, it would sound completely at home on an Echo & the Bunnymen album circa 1984, creating a hypnotic ambiance that becomes more addictive with repeated listens.

This, however, is no mere eighties throwback. The Smiths were unusual in that they were simultaneously original and thoroughly grounded in rock tradition. Likewise, on The Messenger, Marr has one foot planted in rock history and the other planted in the present. “Upstarts” is the perfect example of this, the melody and chord progression sounding instantly familiar while Marr takes periodic timeouts to play atmospheric fills that would make his aural offspring positively ashamed to have even bothered to pick up a guitar in the first place.

The pressing question, though, is how is Marr as a vocalist? Well, he’s more than serviceable. In fact, he’s a surprisingly solid singer. Of course, he has the advantage of being both the singer and songwriter, so he can write around and sing within any limitations he might possess as a vocalist. Plenty of songwriters, though, do exactly that, and there’s never a moment when Marr’s voice detracts or distracts from the album.

Yet, The Messenger does have its shortcomings. For one, the production is somewhat opaque, muffling the overall sound of the album. Even on headphones it sounds like an album being played in an adjacent room rather than pumped directly into the ears. The vocals, in particular, sound pushed back into the mix, a curious decision given the strength of Marr’s voice.

More noticeable, however, is the narrow sonic scope of the songs, which tend to fall into up-tempo tunes with angular guitar riffs reminiscent of post-punk and New Wave. Here, Marr sounds like a disciple of Television, which is certainly not a bad thing.

But Marr’s genius has always lain in his inability to be boxed into a singular genre, and there’s nothing here to showcase his knowledge of folk or rockabilly, not to mention his gift for writing devastating ballads in the mold of “Stretch Out and Wait” or “Please, Please, Please Let Me Get What I Want”. The Messenger, indeed, is a fairly one-dimensional representation of Johnny Marr.

Then again, Marr is smart enough to know that nothing he could ever record could ever match the magic of the Smiths — and he’s smarter not to bother to even try. Instead, on The Messenger, he finally seems comfortable enough to step out of the long shadow of his own legacy and simply write songs that both he and his fans long to hear: songs that showcase Marr’s talents as a guitarist (even if they don’t showcase his scope) and introduce him in a new, post-Smiths context once and for all.

No, The Messenger isn’t groundbreaking or iconic in itself, but it’s thoroughly enjoyable music from a groundbreaking and iconic artist. It’s as if Marr is saying that he needn’t live in the shadow of his legacy any longer, that all he need do is enjoy himself and stay true to his muse. That, perhaps, is the message he’s needed to deliver for quite some time now.