At first glance, Becoming Traviata (Traviata et nous) is chronicling the rehearsals leading up to the 2011 Aix-en-Provence festival production of Verdi’s La Traviata. But the documentary does something else, too, as director Philippe Béziat uses the opera’s structure to inform that of his film, dividing it into three acts that correspond with those of the opera. Doling out bits of the opera’s plot, the movie ties the fictional drama of Alfredo’s longing and Violetta’s slow dissolution to the performers’ efforts to portray those emotions, revealing the denouement of both narratives only at its end.

In so doing, Becoming Traviata — opening in theaters across the US, and in Chicago on 7 June — renders the opera’s production operatic, without succumbing to the overwhelming artifice that can make opera feel anachronistic in the age of reality entertainment. It’s a clever and remarkably effective way to update a mode of performance whose pantomime can seem bombastic when the camera zooms in close.

The approach helps to reveal the nuance of such performances. Though French soprano Natalie Dessay has the lead role, she is nearly upstaged by the matinee idol looks and throbbing voice of her costar, American tenor Charles Castronovo, when he first shows up. She certainly seems to find him charming, hesitating and mincing her way through their initial encounters. Castronovo, on the other hand, is all guileless braggadocio, and the two of them form an amusing parallel to their characters’ movements.

The early moments of the film, when these two are just beginning to work their way through the score and mold their voices to its demands, indicate the musical heights the singers promise to scale. When Dessay is first coached by the opera’s director Jean-François Sivadier, she holds the power of her voice in check and steps through her staging as though she were unconvinced of its worth. But when Castronovo makes his entrance in the rehearsal room without holding anything back, she endeavors to match him. It takes her a few minutes to do so successfully, and these initial moments of failure are all the more involving for laying bare the process of transforming a series of directions into a full-fledged drama.

That process in turn reveals both Dessay’s and Castronovo’s enormous talents. A case in point is their rehearsal of the famous “Un dì, felice, eterea” duet: at first, Dessay swallows a tricky vocal run, leaving Castronovo hanging on the top note alone. She apologizes, and as they quickly give it another go, suddenly their voices are soaring together so achingly that it’s hard to believe there was ever a time that they weren’t, much less that it was mere seconds before.

Becoming Traviata repeatedly underscores the value of collaboration, among multiple elements in the production. When conductor Louis Langrée tells the chorus that their pianissimos should convey breathless excitement, it seems like a common enough direction. But when they run the passage again, and the excitement is suddenly palpable, an instruction that seemed procedural is transformed, now crucial to the entire enterprise.

As the film attends to detail, so too does Sivadier. He keeps up a constant dialogue with each of the singers, explaining and re-explaining the minutia of a character’s motivation until his original point is very nearly obscured. Dessay makes for an excellent foil here, translating his theory into layman’s terms and puncturing particularly lofty statements with a well-chosen quip or a saucy wink. Their back-and-forth will seem familiar to anyone who has ever seen a behind-the-scenes featurette on a DVD, and holds a similar appeal for those interested in the process of putting together an immensely complicated work of art.

Dessay is unarguably the star of both the film and the opera, alternately self-effacing and confident. It’s a dichotomy that Béziat highlights through elegant, evocative shots, like Dessay idling balancing on the divider between the orchestra’s pit and auditorium just after the company has moved from the rehearsal room to the stage, an image imbued with a sense of physical and artistic risk that is all the more affecting for being so casual.

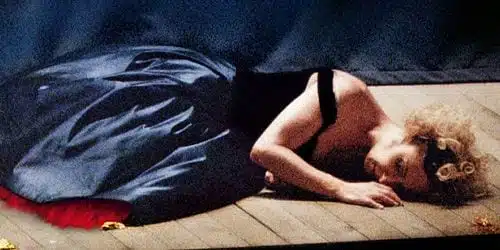

A similar moment comes at the end of the film, when Dessay practices falling onstage. A movement coach shows her the technique, and Dessay tries it once, then again, then again and again, and all of sudden, all she’s been doing for the last five minutes is falling down over and over, a sequence that is both absurd and somehow sublime. These are the actions of someone who is both an artist and a workman; in rehearsals, Dessay sings an octave lower than Verdi’s music mandates, presumably to save her voice for when it’s needed to impress. She knows when to withhold and when to give.

Glimpsing these different personalities and talents coalescing in Aix-en-Provence helps us to rethink opera more broadly, a form known for the thoroughness of its fantasy. The camera lens’ relentless observation puts the emphasis on the intricacies of the process rather than their outcome, and the product is so fascinating that it’s something of a letdown to see bits of the finished opera, which appear here as distanced and mannered after the immediacy of the rehearsals. In this performance, Verdi’s music is beautiful, thoughtful, and also somewhat remote. But when the singers encounter it for the first time, Dessay and Castronovo circling each other like the new lovers they are supposed to portray, Verdi’s music is raw and electrifying, expressing both the feelings of the characters and the people portraying them, an artistic journey whose moments of transcendence are all the more stunning for their transcience.