Of all the talents I wish I possessed, the ability to paint is the most desirable. While doubtless like a lot of people, I’ve pushed paints around canvases in feeble approximations of expressionist “feelings” or in lame imitation of some masterpiece ripe for theft, I’ve never achieved that most important attribute, more elusive and mysterious: the acquirement of a painterly eye and a coordinating hand. That is, the ability to break down into graphic elements — volumes, planes, spheres, and most importantly lines — the natural world, then reassemble them according to a specific temperament, a sensibility, a worldview expressed through a style. Not that I insist on being a master, but I wish I could just know a bit of what a master knows, or how a master works.

Understanding Art: Hidden Lives of Masterpieces is a five-episode series documenting the Louvre study days, wherein paintings are taken off the walls of the famous museum, unscrewed from their frames, pulled from their glass casings, put on easels and scattered informally around a room to be eyeballed by a group of international professionals. Such an exercise sounds both fraught and fascinating, as the paintings are so precious and, well, expensive, if not “priceless”. But the milling professionals are curators and historians, restorers and scholars, and a tasteful camera, both handheld and stationary, mills with them, eavesdropping on their oft-times interesting and just as oft contentious insights into these absolute treasures of art history. The series includes paintings by Raphael, Rembrandt, Poussin, Watteau and Leonardo.

Though we get to hear a good portion of the multi-lingual exchanges and lectures on the museum floor, mostly the series is narrated, a pleasantly unobtrusive and highly informative compression of the history behind the paintings and the painters. This narration is amended with simple bold-line animations, borrowed partly from designer Saul Bass’s title credits for the film The Man With the Golden Arm (1955). Playful, inventive and lively, these animations are also strategically placed; just when the program may be getting a bit specialized for the layman, the animation comes to assist, visually illustrating processes of composition, restoration and framing, or damage control both beneficial and appalling. The animation doesn’t dumb anything down, but explicates in a diagrammatic, dynamic and lightly humorous way.

So we get multiple perspectives literally and figuratively, vocally and visually. The camera gets right in there, as close as the experts with their magnifying glasses, face-to-face or nose-to-nose with Raphael or Rembrandt. Such extreme close-ups allow a sense of the topography of the canvas, not just the cracks and the fix-ups, but the hand behind the work, and the hand at work.

Through modern techniques of forensics and radiology, we witness the revelations of underdrawings, the hesitancies or, as one historian puts it, the “painter’s indecisiveness”. The minutely subtle changes in the eyes of a Raphael portrait, for example: Where should the figure be looking? At the painter? At the spectator? At something just off-frame? Or at their own self-image as they imagine it to be? A fractional move makes all the difference.

Such close inspection, combined with the history offered by the narration and the expert interjections, humanizes the artists and the art. It’s sometimes easy to forget that the Old Masters walked the same planet as us, in the not too distant past. Their subjects seem, for non-historians anyway, remote and rarified, nothing like the blandly familiar men and women of our own age. That is, I suppose, the retrogressive allure of pre-modernism, or pre-modernity — the desire to transport or glimpse into a time and space that seems almost otherworldly. Almost.

In truth, the artists’ contemporaneous worlds were no more innocent than our own. The Old Masters may have coded their works in a slightly different way than modern painters, for example — monarchal compositional concerns, such as profiles representing royalty, given way to some degree to the expression of more internal states of mind — but there remain strong parallels between the older painters and the moderns. One historian links Raphael’s capacity for multiple and simultaneous “pictorial approaches” to Picasso’s mastery of varying co-existent styles, while another states that although both Poussin and Cezanne were “bad at drawing”, each built paintings full of refinement and clarity.

Attribution is probably the most crucially contested issue, particularly when it comes to Rembrandt. The once 800 paintings attributed to the artist are now guessed — guessed, mind you — to be 300, a staggering downsize. One of these paintings is the Slaughtered Ox, a work obsessively re-imagined by the modernist Francis Bacon. A truly “non-vegetarian picture”, as one expert puts it, the Slaughtered Ox in close-up appears almost purely abstract, like a fragment of an Asger Jorn. Its pungency is further enhanced by the revelation that Rembrandt knowingly painted the work on a hunk of worm-eaten wood, a fact only verifiable through modern x-ray techniques. A rancid piece of wood for a rancid slab of meat.

Other insights, among many, include the perilous trajectory of provenance surrounding Poussin’s “Flight Into Egypt”, a painting discovered to have a double by Anthony Blunt, art advisor to Queen Elizabeth and also a KGB agent (!). Or how Watteau, extremely prolific for having died at age 37, was essentially the originator of the fete galante genre, a kind of lover’s picnic, the most famous example of which is his Pilgrimage to Cythera, with its twists of paint as people. The “highly original” off-center positioning of Watteau’s Pierrot is here exposed as the result of careless shearing, a botched scissor-cut disabusing century-long notions of singularity.

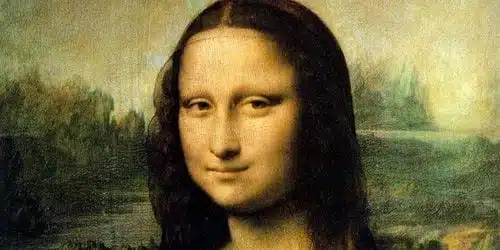

The series ends fittingly with the great Leonardo da Vinci who, despite the immediate familiarity of his name and his often prophetic philosophical output, completed only 15 known paintings, including figures with inexplicable, almost lascivious expressions, none more famous than the Mona Lisa. Always granted the pronoun “She”, she is greeted here by the experts with reverence and joy — and a collective groan when she’s taken away from them.

Such a consensus among experts is somewhat unusual in the series. Interpretations are numerous, and sound, but ultimately mere hypothesis. No matter how close the curator’s, historian’s, or our own noses come to the canvases, there are some things that will remain unknown, or as one curator puts it, “unresolvable”. Still it’s kind of funny seeing six or seven professionals surround a painting and discuss with heated consequence whether a portion of a canvas is a sleeve or an angel’s wing. But it matters, if art matters.

Erudite, engaging, entertaining and well-paced, Understanding Art is as close as nearly anyone will ever get to these great artists and their paintings, not just cheek-to-cheek, but, with any luck of transference, mind-to-mind.