If you’re close to my age—and I hope for your sake you’re not—you may remember a quintessential haunted-hospital image at your local video store. This would be the box art for a 1982 movie called Visiting Hours, and it featured a high-rise medical facility pictured at night, its window lights judiciously turned on or off to create the likeness of a pixelated death’s head. In one poster the artist manages to sum up what’s frightening about not only modern medicine, but also modern life generally: its inscrutable technologies that do as much harm as good, its impersonal regimentation, that foreboding feeling of being trapped in a matrix, unable to see the sinister truth past the walls that surround you. The patients in Visiting Hours presumably don’t even know the death’s head is there.

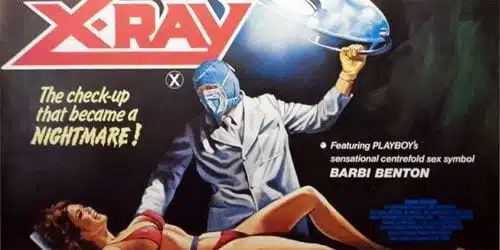

Unfortunately, nothing nearly this clever is going on in X-Ray (née Hospital Massacre), the top-billed feature in a new two-film DVD from Shout! Factory. Blame for this film’s shortcomings falls squarely on its makers, though, because by any measure Shout!’s restoration of X-Ray looks tremendous. Its picture is clear and sharp, with just a hint of the powdery granularity of traditional 35mm film, which is nice because it allows you to really see how poorly applied everyone’s makeup is and how greasy all the actors look. There’s not a hint of print damage or scratching, which is also nice because it lets you make out how the crew seems not to have bothered with set design at all and instead just set up shop in a hospital and started filming.

You’ll thrill as naugahyde waiting-room chairs and plastic ferns on end-tables shimmer across your plasma screen, pristine and perfectly preserved. The soundtrack is flawless as well, so you hear with sonorous fidelity whenever someone reads a line as though they’d been drugged with a quart of Robitussin. It’s like taking a time machine back to 1982. Or, more accurately, it’s like not wanting to take a time machine back to 1982, but having to do it, anyway.

X-Ray is one of the very few movies ’80s horror scholar Carol Clover saw fit to openly accuse of misogyny; she was typically quite forgiving when it came to the gender politics of flicks about diced-up teenagers. I can see Clover’s point—no Final Girl is Susan (Barbi Benton), who spends most of the movie high-heeling from one position of peril to another and fearfully begging men for help—but it’s hard to get too worked up about it, as nothing dramatic ever actually happens in X-Ray. I mean, yes, as befits a proto-slasher there are the requisite, mostly motiveless murders, but they’re invariably predictable and committed in virtually the same way.

We would fret for Susan, theoretically, as she tiptoes around her haunted hospital, perpetually menaced by a snubbed childhood suitor, only director Boaz Davidson seems to have confused the act of creating suspense with that of passing time, with the consequence that X-Ray is chalk full of the latter. In lieu of hanging on the edge of our seats, we sink stupefied into them as Susan neorealistically spins numerous phone rotaries, trying to reach her ex-husband or waylaid daughter. Instead of biting our nails, we study them absently as she tells one unsympathetic doctor after another the same true-but-unbelievable story about the forged X-rays, courtesy of the killer, that are prompting the staff to keep her there by making them think she’s about to die. Note to Boaz: It can only be called “building tension” if tension is actually built. Otherwise, it’s just procrastination.

Better than X-Ray, but still not any good, is sibling slasher Schizoid, which has an unhinged killer systematically skewering members of a therapy group with a scissors. My inside sources at Google tell me Klaus Kinski, who plays the group therapy shrink, was a fine actor. That may have been true generally but his performance here seems to have inspired Tommy Wiseau’s in The Room. He whinges. He wheedles. He wanders around. He squints out the same look of constipated concern no matter the circumstance. He leers creepily at Allison, his biological daughter, as she showers. He says her name more often than Cloverfield’s cameraman says “Rob.”

If there’s any pleasure to be gotten from watching Schizoid–and there’s not—it comes from marveling at some of the early appearances by familiar performers. Aside from Kinski, there’s also Craig Wasson (hero, if that’s the word, of Brian DePalma’s also-not-at-all-misogynist Body Double). As well, diehard ‘70s sit-com buffs (both of you!) will recognize Donna Wilkes from the short-lived Diff’rent Strokes spinoff Hello, Larry. Unfortunately, once their performances cease to be amusing as camp, the movie devolves into a joyless exercise in plot twists that fail to surprise, murders that fail to horrify, character exposition that fails to intrigue.

Still, I’m glad this compilation exists. Both X-Ray and Schizoid are individual tests in a broader battery of mid-’70s / early ‘ 80s medical anxiety films, Coma, the main, being supplemented by Rabid, Embryo, The Manitou, Parts: The Clonus Horror, Good Against Evil, The Lazarus Syndrome, and countless others. These titles hold up hospitals and clinics as sinister labyrinths of mayhem, where bureaucratic muddle yields terror and death, Satanic covens readily take up residency, and even the experiments of well-meaning medical researchers conjure post-human sociopaths.

The fears X-Ray exploits are manifold and topical: anxiety about the fledgling H.M.O. system championed by Richard Nixon; misgivings, both legitimate and blindly ideological, over Roe v. Wade; the refinement of ever-more Frankensteinean high-tech medical procedures like organ transplants, cloning, and mood-managing pharmaceuticals. Though I doubt X-Ray’s makers had much of this in mind when they made the film, it still manifests the American zeitgeist of the time, wittingly or no.

Anyway, there’s a certain value in the film’s guilelessness. Cleverer med-thrillers use the trope of the haunted hospital as a springboard to delve into meatier issues. Rabid vamps on Cronenberg’s usual infatuation with body horror and damaged sexuality; Embryo, centering as it does around a test-tube baby grown overnight into a grown and preternaturally gifted woman, challenges us to ponder the rift between intelligence and wisdom. X-Ray does no such thing. It’s a movie about a guy in a hospital who kills people. Period.

Klaus Kinski in Schizoid (1980)

Schizoid isn’t even as focused as this. It has an international feel, with Pieter, Kinski’s character, being German (probably just to either account for or take advantage of Kinski’s accent), his daughter Allison being American, and the wife and mother who brought Allison into this world, being dead. Over and over the movie refers to this, as Allison, a-whirl with hormonal teenage angst, dons her late mother’s dress, pilfers Pieter’s loaded revolver and goes joyriding, or mails threatening letters to his new girlfriend. When a mewling, enabling Pieter gently calls out this troubling behavior, Allison goes even more haywire. “I’m an American!” she shrieks as Pieter entreats her in LANGUAGE, hoping to calm her. “Speak English!” To punctuate, she rips the irreplaceable dress in two and chases Pieter’s distraught girlfriend out of the house.

A strangely prescient moment, this, though again, I doubt the movie meant to make any predictions. This was, after all, an era when Americans were plagued with doubt—hostages abroad, gas lines at home—but largely valued abroad as a bulwark against the Soviet Bear. In keeping, Allison’s repugnant, selfish nationalism is pitched as an arrogance masking the tortured despair of a grieving child. Were the same movie made today, though, she’d probably be the hero.

* * *

The extras include a few interviews — nothing special.