The subtitle of this book, “An American Life”, has been applied by many previous chroniclers of other people’s lives, but in Jack London’s case, it fits well. Earle Labor has made London’s life and work his lifework during the past half-century. Labor introduces a man who roamed not only the Americas but Asia. He set off when only a teenager. Labor corrects London’s boasts by corroborating his claims against testimony of his friends and family– and the historical record.

Sympathetic to London’s compassion, energy, and ambition, Labor compiles a sober, smoothly told, careful study which will prove a definitive, comprehensive biography. Labor emphasizes the life far more than any work, so this is not a critical examination of his writing, but a retelling of London’s career.

As an early pal saw London, he strove “to be the conqueror”. This, Labor argues, was London’s greatest asset and his greatest liability. A born tale-teller, he embellished his own family’s hardscrabble but never truly impoverished condition. He was raised around the Bay Area, where he was born in 1876 in San Francisco. His putative father denied paternity, and London appears to have been born illegitimate.

He came of age during the settling down of the frontier, and his family tried to farm on and off around the Bay Area without lasting success. Tough times by the 1890s, akin to our own Great Recession, found many conniving employers trying to profit from their own start-ups: the factory system with its increased automation, doubled workloads, and slashed payrolls. London had, in shoveling coal for the electric utility and in running a laundry, twice to do the work of at least two men laid off before he was hired. The first job reduced him to a wreck. After the second such lowly paid and repetitive, dangerous job feeding a machine, he refused to bow to the “work-beast” again.

Instead, he relied on his strength, his determination, and his wits. A voracious reader, he yearned to be a writer, but he failed for a while to get even his imitative hackwork accepted. Nineteen hours a day, he turned into another kind of machine, calculating what the mass-circulation magazines wanted, as improved technology accelerated a cheaply made, illustrated medium, an action-packed short story for busy but “virile” male readers. He finally sold a couple of “yarns” at the age of 21. Most writers at this stage would have little to go on from their experience. London had plenty.

Labor takes us through London’s early years, already crammed with possibilities for the later London to draw upon. At 14, he worked in an Oakland cannery. At 15, he was an oyster pirate in the tidewaters and estuaries around his East Bay. At 16 he tramped across America, becoming the hobo’s highest rank, the “profesh”, before returning back home to sign on as an able-bodied seaman, quite a feat for a 17-year-old. He went off to Japanese waters, gaining the global exposure he would soon put to good use for his stories and reminiscences.

At 18, he joined millions of desperate, destitute men in Gilded Age America marching east to protest at the Capitol, as part of General Kelly’s Army of the Unemployed. A grifter with a smile, London could talk up a smooth line to finagle goods and generosity. He stuck it out until the Midwest, where bad weather and wary townsfolk put an end to his schemes. He went on, riding the rails to Niagara Falls. He watched its moonlit vista until midnight. That next morning, arrested for vagrancy, he was sentenced to a harrowing month in Erie State Penitentiary.

Nineteen found him at Oakland High School, cowing his classmates with his “truculent” Socialism and his gruff manner. His curly hair and open-faced good looks undoubtedly improved when he received an upper plate to fill in his missing front teeth, and when he started to brush them for the first time ever. He crammed for admission to the University of California but soon, finances forced him to drop out. After his experience as menial laborer, he vowed to find a better way to make a living.

Then, the 1897 Klondike Gold Rush spurred him and his uncle north to the Yukon. Labor memorably captures the excitement and dread of this hyped event. While we never learn how London eked out his five dollars worth of gold, this is not Labor’s concern. He wants us instead to learn how London began to listen, watch, and ponder what he saw all around him. Out of this, soon after, nearly 80 stories would emerge when, finally, he left hard labor behind for a career as a paid writer.

What distinguished London from his contemporaries who had beaten him back to cash in on writing about the Klondike and the Northland, Labor finds, was London’s “human interest, romantic imagination, and sympathetic understanding”. He gets the silence in, the primitive pull of the landscape, where its woods and animals lurked, and where foolish men fell to the harsh climate. Although late to the rush to get the Yukon down on paper, London’s fiction remains in print today.

A popular writer, one whom before Labor chose him for his dissertation in 1961 lacked respect among the professorial establishment, London for Labor represents not only a dynamic, clever hustler, but a man in thrall to his own vitality, however dampened by his weakness for alcohol — as a teenager, already he had a near-fatal poisoning one night. He scrapped, he connived, and he conned. He watched other men give in to weakness, and among tough guys, he soon got the hang of survival.

London wisely slowed down, somewhat, once he found a publisher. At a thousand words a day, six days a week, by 1900 this “Self-Made Man” was acclaimed as “the American Kipling” with a similar knack for conveying high-minded ambitions in vernacular, jocular terms, and with a commitment to convey on paper the voice and temperament of an observer vowing to remain “original”. Both were inspired by Western efforts to colonize and civilize the wild reaches. Yet, London resisted imperialism.

Drawing on his own radical tendencies and encounters on the road of hobo and tramp sailor, London balanced his hard-headed nature to cash in as a professional, stable writer (he was the first to combine his reportage with photography) with his political and social concerns. He ran for Oakland mayor on the Socialist ticket, gaining only 246 votes. As fame beckoned, he tried to remain unpretentious. While his romantic life turned rocky — on the rebound from his muse and eventual if brief mistress Anna Strunsky, he proposed four days later to another woman, Bessie Maddern — he gained renown as he was drawn into the inevitable “Crowd” of Bay Area bohemians. His tales earned him success.

The Call of the Wild (1903) remains his best known book; he signed away the rights to Macmillan for $2,000, but on the other hand, he rationalized, that publisher put out many of his lesser-heralded works, to even the accounts. He helped invent, long before Tom Wolfe, the New Journalism ca. 1902 when he went undercover into the slums of London’s East End, for The People of the Abyss.

Fighting depression, he channeled the breakup of both his marriage and his affair with Anna into a love story inspired by his Japanese voyage, The Sea-Wolf. He fell in love with Charmian Kittredge, schooled by her aunt in “free love” and unmarried into her thirties, having wooed married lovers herself–and possessing typewriting skills admired by London. A friend of Bessie’s during his affair with Anna, Kittredge had earned no attention from London until he made a pass at her when she was packing him food that Bessie had sent her to buy for him, as he was off to the resort of Glen Ellen, where London had sought a shelter from his crumbling marriage. No pushover despite her open-mindedness, she resolved to have an affair on her own terms. Playing London to her advantage, Kittredge came out of their first week with a lifelong lover. “To protect Charmian from suspicion, Jack advised her to stay in touch with Bessie, adhering to her role as confidante.” This scandal perhaps bettered any fiction.

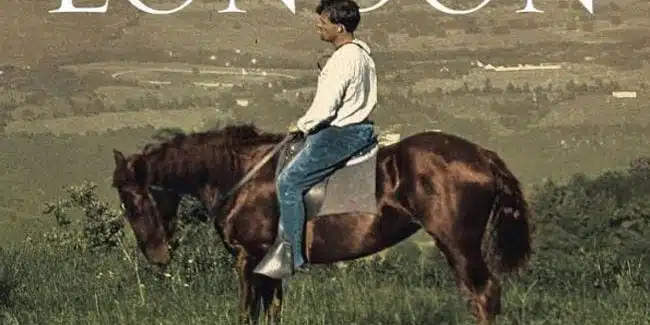

Confused by his passion for Kittredge, his guilt over Bessie and their little daughters, and his wanderlust, London went off to cover the Russo-Japanese War in 1904 for the highest bidder, William Randolph Hearst. Deep in Korea after he watched mounted Cossacks charge an old walled city, London learned that due to a blunder at Hearst’s Enquirer, Kittredge’s letters had been forwarded not to himself but to Bessie. Expelled from the conflict after he decked an insolent Japanese officer’s groom who had stolen fodder meant for London’s horses, the notoriety boosted his career. Teddy Roosevelt cabled a diplomatic protest to the Japanese, who released London from custody.

Docking in San Francisco, London was served with divorce papers, and a headline in the hometown Chronicle. Bessie on her lawyer’s advice in what they thought was a sealed case had chosen to defame Anna rather than Kittredge. A newspaperman gained access to the file and made his scoop.

His relations with Kittredge proved rocky after, but she proved loyal when he did not. London amused his friends by his socialist proclamations when he hired a valet-cook-housekeeper: Manyougi, the same helper who had caught the groom’s theft in Japan. Yet, his affection for his companion endured despite his bourgeoisie habits, and his expense account–lessened considerably after Bessie’s alimony.

Restless, he wandered on the waters where once he stole oysters, and he toured the lecture circuit, preaching revolution to acclaim in Berkeley and shock in Stockton. One night at Glen Ellen he slept a whole eight hours, double his usual quotient, and he marveled at the difference. In 1905, he moved to the Valley of the Moon, his rural haven, 50 miles north of the Golden Gate: “I found my paradise.”

Still, he would be pursued. He needed money to expand his holdings in Sonoma County. On a lecture tour in Illinois he married Charmian only to find out he violated that state’s law. The newspapermen circled again, and the negative publicity of one who had abandoned wife and children in retrospect seems to have increased attention for his rabble-rousing, radically leaning lecture tour back East.

The year 1906 found him an eyewitness to the fires after the San Francisco earthquake. Sparked by Jane Addams’ Hull House in Chicago and Upton Sinclair’s invective against the stockyards, London stirred up a potboiler predicting revolt. Yet The Iron Heel, despite in Labor’s terms being London’s bravest, if not his best book, met with a tepid reception from the socialist press. However, with the rise of fascism and its communist enemies, his book earned a belated audience.

Sailing the sloop Snark to Hawai’i and the South Pacific, London and Kittredge landed on the Solomon Islands, eluding a volcanic eruption. The couple and their crew suffered malaria, yaws, fevers, and for London, hives and fistulas. Its indentured natives fared worse, in what Labor equates to the Belgian Congo as the “most damning evidence of colonial rapacity”. The pair fled a harsh copra plantation, where two of its British overseers soon after were beheaded, and a third succumbed to dysentery.

Back in California, the charm of Beauty Ranch and a custom-built Wolf House provided retreat in Sonoma County. In Carmel, Sinclair Lewis struck up a brief story-swapping deal, while in Los Angeles, amidst “hackwork”, London supported anarchists in the Mexican Revolution, and met with agitators Emma Goldman and Lucy Parsons. His stress increased, worsened by a set-up fight he was drawn into, amidst the sorrow of losing his daughter with Kittredge, Joy, after only 36.

More publicity followed. By 35, London was “firmly established as headline copy for every newspaper in the country” and as Labor reminds us, before radio, the press possessed massive influence. London welcomed attention, but he also needed a rest, as his health suffered from the tropics. Inspired by the ranch and his love for Kittredge, he wrote his longest novel, The Valley of the Moon.

At the start of his unlucky year of 1913, he contributed installments of his “Alcoholic Memoirs” to The Saturday Evening Post. Blight, death, shootings plagued the ranch, where Kittredge, after a miscarriage, flirted diligently. A jealous London, recovering from an appendix operation and with kidney ailments, had to mortgage one ranch property to finish Wolf House before winter. Four days later, the new home burned down. Joan, one of London’s older daughters with Bessie, sparred with him. His investments failed him, too. By the end of the year, he had $10 as his total bank balance.

He split with the Socialist Party, beginning with the Mexican revolt, affirming a firmer “big brother” in the guise of Uncle Sam was needed to save the nation from “herself”. On his ranch, faced with bankruptcy, he had to turn entrepreneur and write to support his family and his beloved retreat. His schemes to lend his name to grape juice and his earnings to plant eucalyptus trees floundered. Although the highest-paid author in America, with a million books sold by Macmillan, he found himself pitching “crackerjack” serials as “a dog writer” to grab “the biggest public I have”.

Another Hawaiian cruise and a visit with Wyatt Earp and film director Raoul Walsh in Hollywood followed, but London’s system had filled with poisons. His dissolution deepened, his animosity towards his daughters grew, a lawsuit over riparian rights on his ranch consumed him into his last month alive. Ranting, he wrote, faithful to his routine. But his longtime allies began to keep their distance.

Late in 1916, despite or because of a daily diet of duck, he succumbed to uremia. He was buried “beneath a giant lava boulder rejected by the builders of Wolf House”. Labor concludes with a nod to the pilgrims who continue to visit the grave, nearly a century after London’s death.

Those visitors continue to read London’s fiction and journalism. Outside of this circle, for whom Earle compiles this intimately told account, fewer may recall much about this media-savvy author’s impact. Labor amasses the details, drawn from reliable sources. While his results may cause the curious to marvel more at London’s frenetic pace rather than the more than fifty books he found time to produce, his life remains engrossing.

Perhaps London pioneered the style of the bestselling adventurer and rogue; his lecture tours anticipated the talk shows and book signings accorded his equivalents today. Separating the claims of many previous biographers from the facts, Labor’s report of London’s vital if too vigorous (given his premature demise) gadabouts tells his own brawny epic.