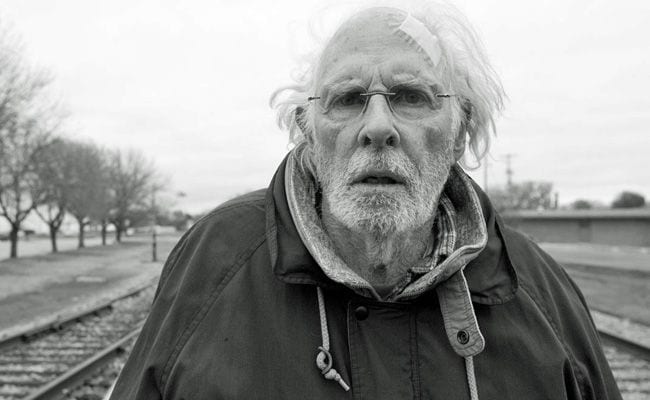

Think for a moment of Bruce Dern’s face. This might be the most resonant effect of Nebraska, a movie that offers any number of beautiful views — wide Western US vistas, horizons stretching forever, trucks and saloons and skies, all rendered in a black and white that’s stark and stunning. Still, for all the space and distance conveyed in the film, all the roads and highways and railroad tracks, it finds a most incredible depth of field in Bruce Dern’s face.

More accurately, of course, the face in Nebraska is only partly Dern’s. It also belongs to Woody Grant, the man Dern inhabits so wholly here. When you see Dern elsewhere, not in the movie but in an interview, for instance, he looks less haunted, perhaps, more detailed, less like an old man, more like a veteran performer who knows how to work a camera, how to tell a story. Woody’s particular look is both familiar and hard to describe, part vacant or haunted, maybe, part wily.

When Woody looks off to the distance or quite past his son David (Will Forte), who wants more than anything to be seen by his dad, acknowledged and known, his face suggests a kind of looseness, as if the mind behind it is receding and the exterior is only that, not expressive but removed. But then you might look again at Woody, as he stands in the background of a scene where David talks about him, to his mother and Woody’s wife Kate (June Squibb) or to Ross (Bob Odenkirk), David’s brother; as they ignore him, unconcerned that he might be hearing them, you might get a different idea. He’s not responding to what they say, but he may be absorbing it.

Or maybe he’s not. Woody’s great unknown lies within. And as such, it provides at once a weight and lightness for Alexander Payne’s film. Structured as a road trip like so many of his movies, Nebraska is less overtly instructive than those, messier and also more elegant. It posits Woody’s journey not so much as his means to self-discovery, but maybe yours. He and David undertake a drive from Billings, Montana to Lincoln, Nebraska, some 800 miles. Woody insists he has a winning ticket for a million dollars, one of those magazine subscription come-ons that depend on the not-so-small print (when he reads, “You might be a winner,” he seems to miss the “might be” part), and despite Kate and David’s resistance, Woody makes repeated forays onto the highway by foot, so stubborn and desperate to get moving that David agrees to drive him, if only, as he puts it to his dad, to “shut you up.”

Kate stays behind, until her men make a detour to Hawthorne, the teeny Nebraska town where she met and married Woody, and where assorted relative still live. Here you discover, despite and because of the lack of discovery by the individuals on screen, that everyone’s life is something like Woody’s. His repeated setting out, walking as a small figure in a wide shot, suggests he’s feeling restless and unfulfilled, even if he can’t admit it or won’t articulate it. Kate manages her own similar feelings by carping at Woody, and David, who works as a chain-store stereo salesman and misses his just-moved-out girlfriend, might have his own longings. The relatives, an assortment of dolts and bullies, as well as some longsuffering women, tolerate Woody’s visit until they hear he’s got money coming; then they become vulturous.

That the money is a fiction is a narrative trick here, for the film — not unlike Sideways, About Schmidt or The Descendants — is more interested in the characters revealed in reactions both to adversity and good fortune. As David learns of his father’s difficult youth, his reported generosity and vulnerability, he’s startled, for he only knew Woody as a remote, difficult, alcoholic, a man who left his sons feeling abandoned and resentful. That Woody is a war veteran has something to do with this backstory, but so does the population of Hawthorne, including Woody’s onetime business partner Ed (Stacy Keach), still conniving, still angry, still determined to show his dominance over Woody, who somehow escaped Hawthorne when Ed did not.

Ed’s efforts to intimidate Woody again, as well as David, provide for series of close-ups and two-shots, in the town’s manifestly abject bar, amid the mirrors of the men’s room, on the ever-empty street. Certainly, these also underline the sublimity of Keach’s face, as he also conveys an array of responses in mere seconds, his expression complex, simultaneously menacing and regretful, cruel and tender. Watching Keach and Dern more or less literally face off in these moments serves as something of a master class; you imagine the folks on set standing back, muted, awed, grateful.

What they convey here, these men, is a story where the words are beside the point. Whatever Nebraska might be offering in terms of the old associates reunited, the father and son coming to appreciate one another, or even the husband and wife not quite recognizing what they’re got or had or never mad. What Dern conveys, in Woody’s face framed by any number of panoramas or vehicle windows or working class interiors, is a lifetime — make that several lifetimes — of experience, not always good and sometimes not so plainly instructive. But even as Woody’s face reveals loss, regret, and vindication, it also maintains hope, a desire for the life he hasn’t lived, whatever that might have been.

Just so, Woody’s face, so specific and so unusual, also reflects many others, those belonging to people in small towns, who might be working class, not so hopeful, even depressed, in its various senses. It’s not so much that Woody, so determined to believe in the winning ticket, or at least determined not to end in Billings only, embodies any particularly “American” experience, though he might. It’s more that he looks out, that he sees beyond the frame around him, what you don’t see. This is Woody’s gift, so rare in movies, as he presses you to imagine that.