“This’ll be the first video I’ve posted in three years.”

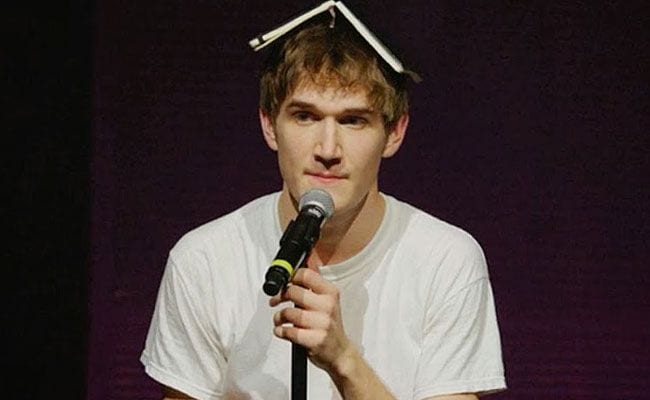

As I speak with Bo Burnham over the phone, he is awaiting the release of his newest special, the curiously titled what., at YouTube’s headquarters. Burnham, whose rise to fame is due in large part to the comedic songs on his YouTube channel, has come a long way from his bedroom in his parents’ house, where nearly all of his YouTube videos were recorded. Following two specials, his self-titled and 2010’s Words Words Words, Burnham has done two bold things: first, he released what., without a doubt one of the most innovative and unforgettable stand-up specials in a great long while; second, he gave it away for free. [I’ll pause for you to make a “giving it away for free joke” here, in the spirit of comedy.]

“I’ve always liked the format of YouTube,” Burnham says, “sharing things for free, which is a nice exchange between people.” Be that as it may, what. could have been a major source of profit for Burnham; it not only displays his creative, theatrical, and boundary-pushing sense of humor, it amplifies it to previously unseen and unheard degrees.

Yet in spite of this financial incentive, and despite a payment from Netflix to allow what. to stream on that site, Burnham released the visual component of what. on his long-silent YouTube channel at no charge to anyone with an internet connection. (The audio version comes with a price tag, but given how much of what.‘s humor relies on visual gags that don’t translate to CD, it’s safe to say he is offering the best facet of his special for free.) Three years in the making, what. is not only a collection of Burnham’s humor at its best; it’s also an indication that he is doing something much more than routine stand-up.

Burnham describes himself as a “theatre kid,” a label unsurprising to anyone who has seen any of his prior comedic material. His affinity for (crude and humorous) piano ballads hints at his aspirations for a mode of performance more Broadway than the Hollywood Improv, and classic pieces like “One Man Shows” indicate that his interest is in performance more generally rather than comedy specifically. what., then, stands as the purest distillation of Burnham’s ethos yet: it’s undeniably hilarious, just as much as any classic stand-up routine, but it takes audience expectations of “regular” stand-up comics and throws them out the window.

The show expands both Burnham’s capabilities and the possibilities for comedy as a whole. (This extends even to the actual footage of the show itself: at the beginning of what, Burnham jokes: “Video editors are so fucking … “, after which the video abruptly cuts to the next bit.) The title what. is a bit odd at first, but ultimately it’s the first word one is likely to say upon viewing the show, whether live or in your bedroom on your computer screen.

One of what.‘s most elaborate pieces, the showy “Left Brain/Right Brain,” depicts the two hemispheres of the 23-year-old Burnham’s brain as in a state of conflict. When I talk to him over the phone, it’s the former hemisphere that takes prominence. Our conversation covered what.‘s free release, his comedic process, and the boundaries of offensive comedy.

what. (Full Show)

Was what. always planned to be released for free on YouTube?

No, not really. It was a hope in the back of my mind that I could do it, and then as the show took longer and longer to make — overall it took three years — I toured it a lot, and then made enough money touring to fund it myself. I thought, it’s taken so long, I might as well just put it out there; it was so much work for me that I wanted people to see it. That’s more important to me than anything else.

Was it an easy decision to make the special free?

Well, I did this with Netflix as well, and they paid me some money for the special. They would have paid me much more if I had just gave it to them and didn’t put it on YouTube, but since I could cover the production costs myself, it wasn’t that big of a deal to me. In five years, there’s no way I’m going to look back and think, “Oh man, I wish I had taken that extra money.” But there is a universe where I’d look back and think, “I wish I had just put this out for free.”

There was a bootlegged version of what. on YouTube for some time, recorded at a show you did at New York’s Best Buy Theatre. You commented on the video saying that it was helpful for you to see other comedians’ shows on YouTube recordings so you could see how jokes develop over time. Do you think, on balance, that it is good for people to record at stand-up shows?

I think the worst about that would be that an audience member is not paying attention to the show. When I see someone filming me, I don’t usually think, “No, man, don’t put this up online!” I’d think, “Hey man, you don’t get to go to shows very often, put down the camera and enjoy it!” I love going to theatre and to shows so much.

When I said that comment on the video, I was talking about how it’s exciting for me to see how comedians’ bits evolve. The fact that my show is documented in that way out there is totally fine. The thing with that video is that at first it only had a couple thousand views, but then two months before the special was coming out, I reached out to the kid and asked, “Hey man, I’m putting this out for free on my channel, could you take it down until I post it, and then you can put it back up?” He agreed to that, which was really nice of him. I think when people see I’m cool with it they’re also cool. My main concern was that I didn’t want people to hear I was putting my show out on YouTube, go to YouTube, see the bootleg and think that was my version.

Usually when comedians worry about this, they think, “Oh, if it gets out there then it’ll ruin the bit.” But the only way everyone will see it is if it goes viral, and the only way it goes viral is if people love it. But again, my first concern is that when you go to a show, you should be present. It’s much more exciting to put the camera down and lose yourself in it.

When did what. start coming together as a cohesive show? I’ve seen versions of the “Andy the Frog” bit, for example, that date three years ago.

I had ideas for it, and probably had things written down, right when Words Words Words was coming out. That special came out in fall 2010, so yeah, it’s been three years in the making. About a year ago, the whole thing was pretty much done, but I thought to go out and polish everything, maybe pack some more jokes in. I’m happy I did that. It’s kind of the model of comedians now that everyone needs to turn over an album basically every year, but for me personally I’m glad I took the time.

In one of the more memorable bits from Words Words Words, you describe yourself as not doing “comedy shows,” but “one man shows.” Do you think that’s accurate of your work? what. seems to challenge what people have come to expect of a stand-up comedy show.

Well, in that bit from Words Words Words I was being intentionally pretentious. [laughs] I was a theatre kid my whole life, and I really enjoyed being in shows where there were lights and loud sounds, and even then I was listening rather than speaking onstage. So with this hour I tried to incorporate voices and backing tracks so it isn’t just me up there singing and talking the whole time. I’m very interested in trying to make comedy shows that are a bit bigger, more theatrical, more of a “show.” Some people might say I’m trying too hard, but that’s a compliment to me. I like to inject a bit of production value and flair to comedy, or at least to my little corner of comedy.

The range of jokes in what. is so broad, spanning songs, pre-recorded bits, and normal stand-up. Do you find yourself usually starting at one particular “place” with a joke? For example, a melody rather than a punchline, or a concept rather than a song?

It kind of comes from every direction. Sometimes it’s a little joke, sometimes it’s a vague concept. One of the bits in the show is a duet between my left and my right brain, which came out of my wanting to do a duet somehow — a duet with just me onstage. A kind of Jekyll and Hyde sort of thing. From there I found the conceit of my left and right brain, and it became quite dramatic upon performing it. Other times a song might emerge from a single joke, or a melody I really like might end up with a joke attached to it. I try hard not to nail down my process too much, because I still feel like I’m finding my moves, especially with me going into new territory. I’m not saying I’m going into territory that no one’s ever gone to before, but certainly for me it was new. So I had to let it do what it wanted to do.

“Left Brain/Right Brain”, much like the introduction to the show, involves a great deal of miming, which doesn’t translate onto CD given the lack of visual component. Was there a hesitance to release what. as a CD for that reason?

That’s another reason why I’m releasing the special for free. I didn’t want to have to say, “Well, buy the CD, but you’ll actually have to see it to get it,” and make people double-dip in having to buy both the CD and the special. Also, I worked very hard on the music for the backing tracks, and I think that if you see the special it’s nice to have the music to listen to. I also have five “bonus” songs that I included on the CD that I’ve worked on for the past couple of years, which I hope in part makes up for the strange miming disconnect.

what. is primarily a special. My other ones may have been primarily CDs, but for this one it’s primarily about it being onstage, being visual.

You’ve done “studio” tracks before on your past live CDs. Has there ever been a thought of doing a full studio record?

For the past couple of years I’ve worked on a few studio tracks, but when they were done I didn’t exactly know how to release them, and I ultimately just put them on my CDs. I definitely like making music in the studio, but I never had it out to make a CD specifically. It rarely happens that when I write a song I know what I want it to end up as; I don’t think, “Oh, now I’ve written this song, it’ll go onstage in my show.” It’s part of a process where I make a lot of stuff and then think, “Okay, now, where can all of this go?” I let the material do the talking.

Do you find that as your material has become increasingly more theatrical that so-called “traditional” stand-up comics have resisted your work?

I always worried that would be an issue, particularly coming from a young kid who found success early, and very luckily and undeservedly at that. But I’ve found nothing but support and generosity from older comics. I think comedians are a lot nicer than the stigma is, at least from my experience. Also, because I felt this was a given thing based on the material, I never performed what. in comedy clubs. I wrote the show as a whole and tried to do the show as a whole. I feel like I haven’t been in the comedy scene in awhile.

Another potential source of pressure in response to your frame comes from the corporate world, which you address in bits like “We Think We Know You” and “Repeat Stuff”. Given your growing fame, is this pressure real for you?

Not really. You have the opportunity to choose to be put under those pressures, to choose to reject them or not. The stuff in “We Think We Know You” comes more from the things I hear about “what young people want out of comedy,” usually coming from people from the older generation. I see young people being dismissed for supposedly wanting only “stupid” and “easy” material, or that they don’t have an attention span longer than three minutes. I disagree with all those statements; I just think they aren’t true. So in that song, when I’m talking to the “agent,” there’s a whole generational gap issue at play as well. I’m saying that our generation wants stuff that is substantial and challenging, as well as thoughtful and endearing. Well, I don’t know if I’m doing that, but I’m trying.

One of the strongest cuts off of what. is the song “Sad,” where you joke about the comedic strategy of satirizing something by doing the same thing in an exaggerated fashion, a strategy that you’ve employed in your humor before. Do you ever ask yourself the stereotypical “how far is too far” question when writing your jokes?

That one is one of my favorites. “Sad” is, for me, about how while that sense of comedy is said to be “risqué” and “pushing the limits,” or even about “practicing free speech,” offensive comedy could really be just mean. Or at least a portion of it is just mean. It’s often said by privileged people who don’t have to experience the thing they’re joking about; they can make 95 percent of the room laugh about something that the other five percent could be genuinely experiencing. I felt fearless in that song to be as offensive as I wanted because the point of the song is undercutting any of the offensive content it may have.

But that song is a direct product of me looking at my jokes and saying, “Do I want to be saying this?” “Do I really want to make a joke about a miscarriage when a woman in the audience might have had one?” I know it’s the comedian’s instinct to say, “Do it, man, nothing’s off-limits! It’s cool, bro!” I don’t know if that’s the answer for me. I don’t worship comedy; at the end of the day I don’t fall to the altar of comedy unquestioningly.

Comedy should be a source of positivity. I don’t want to bully people, and I don’t want people to come to my show to feel terrible about something. So I’m actually very open to having a conversation about what I should or shouldn’t say. Of course, there are statements like, “You should never talk about …” And I don’t agree with those either. But I will gladly look at past jokes of mine and say, “Yes, this joke was just bad or distasteful, it made people laugh at something that’s easy, something that’s wrong to laugh at.” I really have to be open to these questions.

Do you think that as you’ve become more experimental with your work that your fans have continued to follow along your path?

I think so. Admittedly, when I started out my audience was way over what it actually is; by “starting out,” I’m referring to all the YouTube hits and giant numbers associated with my channel, which I knew I’d never reach — I didn’t even want to think about those numbers. I don’t want to monitor my audience too closely, as that can really drive you crazy. But I still think there’s a group of people that dig my stuff.

![Call for Papers: All Things Reconsidered [MUSIC] May-August 2024](https://www.popmatters.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/all-things-reconsidered-call-music-may-2024-720x380.jpg)