Fire background image from Shutterstock.com.

On the subject of narrative identity and selfhood, French philosopher Paul Ricoeur wrote, “The text is the mediation whereby we understand ourselves.” Ricoeur’s work in this vein has been adopted by human rights organizations and academia in connection with testimonials provided by the survivors of atrocities like the Holocaust and the Rwandan genocide.

When it comes to the survivors of mass atrocities, however, it is not enough to simply tell of what one has witnessed. In a human rights context, having a receptive listener for an act of witness matters. Many survivors have promised those who died that their stories will be known to the world. As consumers of such testimony and even ‘art’, we, too, must bear witness to what those who have experienced extreme violence and abuse have undergone, so that their telling has meaning.

In a powerful essay that Susan Minot published in McSweeney’s Journal (Quarterly) in 2000 (republished in Best American Travel Writing 2001: “This We Came to Know Afterward”, she offers what could loosely be considered an “act of witness”. The essay tells of how she traveled as a journalist to Uganda from Kenya more than a decade ago to report on child abductions by rebel groups that called themselves the Lord’s Resistance Army (LRA). Many of these children were forced to steal and kill, and often they were raped and forced to ‘marry’ their captors. Some escaped.

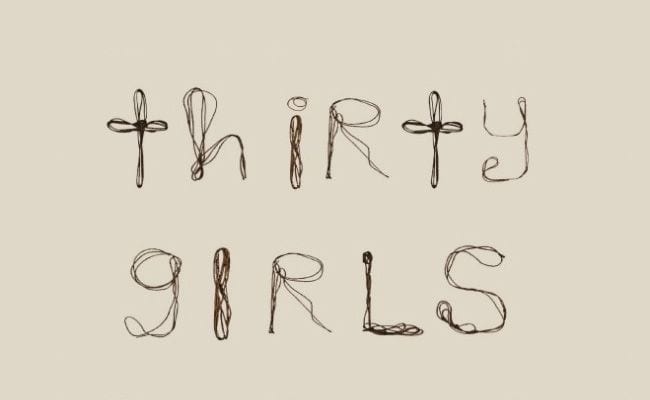

While in Uganda, Minot heard testimonials from some of the escaped girls and a nun working to rehabilitate them. Her latest novel, Thirty Girls, braids together the same two narratives of an American journalist and the story of the kidnapped girls set forth in her 2000 essay, but the results are mixed.

The novel starts with a brief third-person account of the LRA’s kidnapping of teenage girls from a Catholic school. The first narrative (and the more substantially told story) is that of Jane, a glamorous American writer who has taken a journalism gig to chronicle the abductions. Early in the novel, she falls in love with Harry, an independent, restless paraglider. As fans of Minot’s earlier novels will expect, that romance doesn’t go well. The second narrative is told in first-person by Esther, a fierce Ugandan girl who is traumatized by the abuses she observes. Not only must she witness and suffer abuses, but she is also forced to participate in abusing other girls.

Like her other books, Minot’s Thirty Girls deals with wayward men, desire and the subtleties of strong emotions. However, the world described in Thirty Girls — Uganda from the perspective of a tourist and also from the perspective of a native — feels worlds apart from the New England milieu that readers have come to associate with Minot’s fiction.

In Thirty Girls, Minot’s careful observations of emotion are as precise and honest as they were in her rightly acclaimed novel-turned-movie. For example, in trying to tell Harry about her dead ex-husband Jane thinks, “How do you describe hearing your husband say, I think I made a terrible mistake? And what more can you add about yourself if after hearing this you find that no vow of loyalty could have bound you more fiercely to him than this expression of rejection?”

At times, however, this honesty feels self-indulgent, as when Jane and her companions are floating down the river and she thinks “I’m in the Nile.”

She is aware of the romance in the word. The source of the Nile. It was part of the bigger world, of history. Then she thought of how in history at that moment, three hundred miles north of this peaceful gliding river, children were being yanked out of their homes, held captive, raped, infected with deadly disease, and made to kill. The sun shone down as the river carried them along.

This is a truthful scene, a scene that accurately conveys the feeling of being a privileged tourist in a beautiful foreign country with a violent history. But there are too many of these self-absorbed moments in the book, so many that the pacing of the novel suffers.

Jane seems vaguely cognizant that she is in a sharply privileged position next to Esther, but self-awareness alone is not enough to fix the imbalance in the narratives. For example, at one point in the novel, “Jane felt like a white plastic chip in an ancient forest and asked herself again just what she was doing here, in a place she’d never been, going to report on a place she didn’t know about, with struggles she could only begin to imagine.” Because of the time spent circling around Jane’s nuanced emotions and romantic travails, I also found myself wondering what Jane was doing in Uganda and what meaning I could derive from her story.

After a while, it was hard, too, not to be troubled by the cool aesthetic beauty of Jane’s story. Jane’s world is the tourist’s world of “towering eucalyptus smelling of mint” and an evening sun “cracked in a marble sky”. The loveliness of a four-poster bed painted silver. Reiki. Frangipani blossoms. Flying.

Esther’s world is full of violence and the fear of dying at any minute. Of escaping and trying to live with what she’s witnessed. In one of the most brutal scenes in the book, Esther and other girls are required to kill a girl or be killed by the rebels. Esther remembers killing a hedgehog, dissociating for a moment as she and the other girls all start beating another girl to death. But then in first-person, she describes:

Everyone is hitting now. My stick comes down and the girl no longer jumps. Maybe she does not feel it anymore. One hopes this, and to hope this is a terrible hope. Most of the sticks beat only the legs. Everyone fears to beat the head. My gaze looks at what is happening but a small gate in my brain makes a space and I leave through it.

Minot does her utmost to imagine the unimaginable and in many instances renders Esther’s story powerfully. Esther tells the reader,

blockquote>The rebels told us in any case our families did not want us anymore. They would teach us to be in Kony’s family. What they taught me was to hide, my fear and myself. Sometimes it was like dragging a dead animal behind me. Sometimes I felt a thick pad of cotton come over my head.

And soon after: “You walked past children sleeping on the ground then saw they were not sleeping, they were dead.”

Is the cognitive dissonance between these two stories the point? Perhaps. Many readers will be drawn along by the loveliness of Minot’s observations, the depth and clarity of her prose in both narratives — impressed by Minot tackling Esther’s storyline at all and accomplishing so much.

Later in the novel, Jane promises to share Esther’s story with the world because it needs to be known. Thirty Girls is framed as Jane’s fulfillment of that promise. However, if bearing witness is indeed Minot’s intention, this intention is sometimes compromised by the decision to truncate Esther’s experience while magnifying every detail of Jane’s. Jane’s story — that of desire and death — is closer to the ones Minot told in Folly, Evening and Rapture, but in this context, to tell that particular story at the expense of Esther’s story seems a strange artistic choice.

In the real world, we know these stories coexist, of course. As a former American tourist to Africa, I recognized many of Jane’s experiences of aesthetic pleasure and types of epiphanies travel can bring. However, as someone who has studied human rights abuses at the college and law school levels, and has worked for human rights organizations, I strongly questioned Minot’s choice to dwell on Jane’s epiphanies while giving less space to Esther’s experiences. About halfway through my first read, realizing I simply would not be told Esther’s story in as great detail as Jane’s, I found myself trying very hard not to skim Jane’s sections, wanting to get back to the story that felt more urgent. A thought I didn’t have once during any of Minot’s other books.

In The Differend, the philosopher Jean-Francois Lyotard wrote about what he called “the testimonial contract”. He believed that a relationship to further social action through testimonial was only possible when these conditions were met: an addressee that was not only willing to accept the reality of the referent but also was worthy of being spoken to, a language capable of signifying the referent, and the referent itself. The difficulty with Minot’s novel results from the second element — the language capable of signifying the referent.

Minot does an admirable job in a short space of conveying what is unimaginable to most of us, but nonetheless, by book’s end, it remains extremely difficult to imagine. It may be that the only way to anchor Esther’s horrifying experiences for a wide range of American readers was to write in greater detail and at greater length about Jane’s experience as a tourist.

Nonetheless, a book that truly bears witness to the atrocities of the LRA will of necessity be horrifying. It will not be for everyone. It will be hard to read. This book is not as painful as that book would have been, but it is also not quite as strong.