The public face of the small town will always bear the scars of Mayberry and Lake Wobegon. Sure, most towns have plenty of above average children, some of whom even stick around after graduation, and friendly gatherings in barber shops aren’t unheard of even in the post-Supercuts world. But these syrupy fantasies mask the bitter reality hidden beneath.

Writers, especially writers of short fiction, know this better than anyone. There’s something about the confines of a short story which allows a writer to capture the small town experience better than any novel can. Maybe it’s the comparable size — there’s less room to move around, less space to populate. When it’s good, you want to stick around for a while, maybe linger over a phrase or two, and when it’s bad, you can’t get out soon enough.

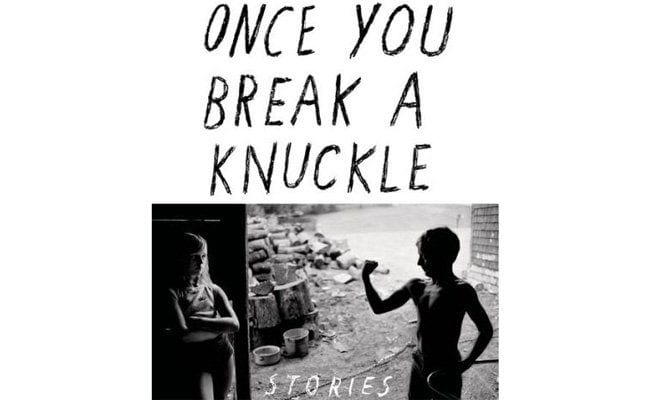

Of course the small town isn’t strictly an American phenomenon. Released this year in paperback, D.W. Wilson’s wonderful collection Once You Break a Knuckle takes the Kootenay region of his native British Columbia and fills it with down on their luck electricians, troubled teenagers, and a Mountie whose taste in t-shirts runs from the comical (“Don’t Writer Cheques Your Body Can’t Cash”) to the sinister (“Cops Only Have One Hand–the Upper Hand”). Wilson’s stories are more than just small town tales, however. There’s a lot of space here, a sense of the vastness of the Canadian wilderness which surrounds and sometimes envelops his characters. We are right there with him in the snow and woods and the mountains.

The bare bones of Wilson’s biography pop up again and again in his fiction, from his time on the judo mat to his father’s service in the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP). That’s not surprising for any writer of fiction, especially one who’s not yet 30 years-old. What is surprising is how he’s taken that experience and channeled it into stories filled with the world weariness of a man twice his age.

Wilson’s stories are by no mean depressing or hopeless, but his characters are filled with the kind of resignation and acceptance of the way things are which can only come with age. There’s sadness there, to be sure, but there’s a sense of freedom, too, of letting go and enjoying the world for what it is.

The lead story, “The Elasticity of Bone” introduces us to Will Crease and his father, John, a member of the RCMP who’s about to leave for a training mission in Kosovo. The Creases appear throughout the book, and each time it’s a treat. The relationship between the two characters is a mixture of threats and menace from both sides which masks an obvious affection. John spouts parental wisdom like, “…they toss the manual out with the placenta”, and Will refers to his father only as “my old man”.

The over the top masculinity on display in their relationship, both verbally and physically, is funny and playful, but also sad, particularly in “Reception”. In this story, John returns early from Kosovo after being shot in the chest. His strength is obviously diminished, but he tries to maintain his macho in spite of his injuries. While walking to a friend’s house for dinner, Will watches his father and thinks, “He could’ve been anyone’s dad right then, one more overworked guy who hadn’t slept in days.” It’s a heartbreaking moment, but it also signals the love Will has for his father, whether he’s oozing testosterone or not.

In “Don’t Touch the Ground” the narrator and his friend, Mitch Cooper, run from a group of drunken hicks through the woods before finally getting pummeled. The tension between small town bullies and kids who don’t fit it is pretty standard fare, but Wilson turns it into a horrific revenge tale, one which confirms an earlier story’s assertion that, “Life is a series of events between shitstorms.” Rather than feeling satisfaction at their triumph, the boys in the story carry the weight of revenge like the burden it is.

These feel like stories to be read just before the sun has come up, when you’re the only one awake in the house. They’re not rousing in such a way as to substitute for your morning coffee, and they’re not hazy in the way the world seems when you awake from a vivid dream. Rather, these stories are quiet and still, the way the world is in the morning, when things are just getting going, when your sense of wonder is not yet dulled by the day itself. Wilson walks that line so skillfully that one can’t help but sit back in awe and watch him work.