The year 2013 was such an excellent one for documentary films that Jason Osder’s harrowing Let the Fire Burn wasn’t even nominated for an Academy Award in the Best Documentary Feature category. In any other year it would have been crowned the winner.

This lack of recognition by awards groups and professional critics has pushed Let the Fire Burn to the side while other documentaries like 20 Feet From Stardom, Stories We Tell, The Square, and The Act of Killing get all of the credit. Those documentaries are certainly worthy of our attention, but Let the Fire Burn also deserves to be mentioned as one of the most vital non-fiction films produced in recent years.

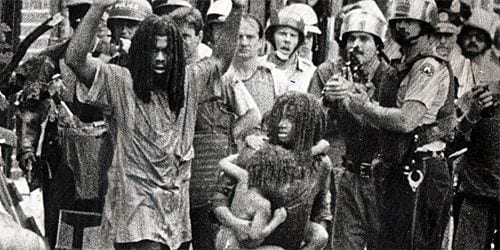

To construct the film, Osder relied solely on archival footage to highlight the heated battle between MOVE, a controversial radical urban group in Philadelphia, and the many government officials and Philadelphian residents who opposed them. Osder’s only agenda was to inform viewers of this incredibly significant, seldom discussed chapter in American history. Let the Fire Burn is void of voiceover narration and any other tricks documentarians use to promote an agenda, and when the final scene raises more questions than answers, it becomes clear that Osder is more interested in presenting the material than preaching what it all means.

Described by Osder as a family, MOVE was founded by John Africa in 1972. Based in Philadelphia, members of MOVE adopted the surname Africa, lived communally, engaged in public demonstrations about issues like animal rights, and opposed modern science, medicine, and technology. Their unorthodox style of protest, like standing on the roof of their house holding toy weapons, made them unpopular in their community.

Throughout the ’70s and into the mid-’80s, MOVE and the city of Philadelphia were at odds with each other. This culminated in a botched police raid on 13 March 1985, in which governmental officials dropped a bomb on MOVE’s house. The explosion set off a fire that ultimately destroyed 61 homes in the surrounding neighborhood and killed 11 MOVE members, including John Africa and five children. Let the Fire Burn ends on this tragic note of ambiguity, and leaves the viewer grappling with many pertinent questions that are still being asked today.

For example, Osder forces us to consider where we draw the line between freedom of expression and acts of harmful disturbance. On the one hand, MOVE frightened its neighbors as they protested with toy weapons and vocalized profanity. On the other hand, the weapons were only toys and therefore harmless, and the language, while foul, wasn’t exactly threatening. Did the members of MOVE consist of noisy, unsanitary neighbors that the neighborhood had to deal with on its own, or were they dangerous thugs who should have been driven out of the city? The governmental officials believed in the latter, but did they ultimately have the right to make such a decision?

Moreover, even if MOVE was acting inappropriately, did the government overreact by literally smoking them out of their house? Surely they must have known that children inside. Osder points out that some of the neighbors who complained about MOVE were more upset that city officials burned down the house, while others believed the fire was the only remaining option. Therefore, to some this situation screams of Attica, and to others, the hunt for Osama Bin Laden, if you will. It really comes down to a matter of perspective, and what you’d be willing to sacrifice for a ceasefire.

To compliment this essential viewing experience, the DVD offers an insightful Q&A with Osder and a fascinating 2002 interview with Michael Ward, the only child survivor of the MOVE raid. Ward’s interview was kept out of the movie for stylistic reasons, and in many ways it complicates the situation even further. For example, one can make a case that the children of MOVE were being used as pawns by John Africa and others, and that the adults of MOVE (who, among other things, fired upon police) were just as responsible for their suffering as were the city officials who burned the row house down.

Challenging films like this rarely catch on with a large audience. However, Osder has delivered an important contribution to the cinematic medium and to recent, racially-charged American history. Nearly 30 years have passed since the flames lit up the Philadelphia sky and burned the MOVE house to the ground. Let the Fire Burn is an uncomfortable reminder that the fire set back then left still-burning embers.