Microphone in front of bright lights from Shutterstock.com.

How you can’t sell your soul to rock ‘n’ roll because it has already sold its soul… There once was a time during the new Age of Aquarius when the length of someone’s hair meant more than the balance in their bank account.

THIS WAS THE CITY, Los Angeles, California. The time was 1968. The scene: 8512 Santa Monica Boulevard, the recording studio of the counter-culture rock band, the Doors. Lead singer and pop poster boy, Jim Morrison, was standing in the middle of the studio screaming, but it wasn’t part of a song, he was screaming at his band mates.

“You made a pact with the devil!” he shouted. “You sold us out!”

“It’s not your call,” Robby Krieger, the Doors guitarist replied. “It’s not even your song. I wrote it.”

“That doesn’t mean shit,” huffed Morrison. “I’m the guy singing it and I don’t sing jingles!”

Morrison had just learned that while he’d been away on holiday the other members of the Doors: Robby Krieger, John Densmore and Ray Manzarek, had agreed to allow Buick to use their hit single “Light My Fire” in a television commercial.

“It’s good exposure, we can use it.”

“Don’t try to justify it. I don’t do deals with the Man! That’s not what we’re about.”

“It’s $75,000, Jim.”

“It’s a fucking car commercial! I’ll tell you what, you go through with this and I’ll personally call up Buick and say I’ll smash one of their fucking cars on stage with a sledgehammer …”

* * *

If you were born any time after 1970 you might be asking yourself exactly what Jimbo’s problem was. The idea of somebody getting upset because some major corporation wanted to give them $75,000 to use one of their songs in a TV commercial seems preposterous. Happens all the time today. Hell, rock stars these days openly lobby to have their music included in the latest Gap or Volkswagen commercial; rappers have rhymed for years about their Rolexes, diamonds and Mercedes-Benzes. Who was this Morrison guy, you might ask, some sort of troublemaker? Well yeah, he was, but that’s not the point.

The point is, there once was a time during the new Age of Aquarius (roughly 1967-1972) when the length of someone’s hair meant more than the balance in their bank account, and calling a rock star a “sell out” was one of the vilest accusations you could level against them. In fact, it was a badge of honor to be perceived as a disenfranchised, disenchanted, dropout, long-haired pot-smoking rebel who would rather kiss Richard Nixon full on the lips than dare prostitute the integrity of your music (i.e., “sell out”) by making deals with corporate America (i.e., “The Man”).

There once was a time when rock musicians openly rejected materialistic society (at least they gave it lip service), preached free love and gave free music festivals. There was a time when they put flowers in their hair, painted peace symbols on their foreheads, cut the soles off their shoes, learned to play the guitar and muttered “come the revolution” the Man would be one of the “first muthafuckers up against the wall”. Consequentially, and not too surprisingly, the Man wanted nothing to do with them either.

To the Man these “commie pinko fags” were nothing but dirty, smelly, long-haired, draft-dodging bums who did nothing all day but have sex, do drugs and bang on the drums like a chimpanzee. It was labeled by Life and Time magazines as “the Generation Gap”, but in a time when the entire world was polarized between the Left and the Right, Conservatives versus Liberals, Young versus Old, Corporate versus Cosmic — it was less a gap than a great divide.

But it hadn’t always been like that. Before the mid-’60s, teenagers were basically harmless. They might have irritated their parents with that “rock ‘n’ roll nonsense” but they hardly frightened them. They were “good kids” who were “going through a phase”, not rebel youths or drug-taking demons. Rock ‘n’ roll was still around, but the beast had been tamed.

So had Elvis.

His stint in the Army had seen to that. He was now churning out songs like “Are You Lonesome Tonight” and movie fluff like “Girls, Girls, Girls”. Teens were portrayed on TV as pleasant and slightly-addled ‘young adults’ and embodied by the likes of Gidget and Dobie Gillis. But there was another side to teendom, a more somber and slightly darker side; the land of the Hipster and the Beatnik, the Folknik with the torn sweatshirt, sandals and goatee who carried “Ban the Bomb” signs.

These kids read Kerouac in coffee shops, they listened to Dylan and Baez, discussed the Vietnam War, civil rights, talked openly about sex and injustice and, most of all, saw straight through the white picket fence and blue sky bullshit being fostered on them by the older generation. It was the early beginnings of the Protest Movement, which officially began on October 1st, 1964, when a University of California student named Jack Weinberg was arrested for distributing leaflets promoting civil rights on the Berkeley campus. Before a police car could take him away, 2,000 of Weinberg’s fellow students surrounded the cruiser, sat down, and refused to move.

The stand-off (actually the first recorded sit-in) lasted for 32 hours and marked the beginning of the Free Speech Movement which shaped the ‘60s Generation, and frightened authorities. Some time later, when officials appointed a young man to negotiate with the FSM, Weinberg famously remarked, “We don’t trust anyone over 30.” Although he admitted later that he’d said in jest, it became the unofficial slogan of the coming counter-culture.

Adults were wary and scared by these developments and by its representatives, and they did their best to diffuse the creeping menace by portraying the kids as dirty bums in the press, and on TV as fangless and goofy cardboard cutouts. (Exemplified by the Maynard G. Krebs Beatnik character on Dobie Gillis, played by future Gilligan, Bob Denver. Maynard said that “the G stood for Walter”.)

The teens viewed them with both curiosity and trepidation; repulsed and fascinated. They represented something serious and dark and so … grown up. Emboldened by the assassination of President Kennedy and the anti-violent message of Martin Luther King, the Beats (as they became collectively known) began to shout a little louder.

But their message was soon drowned out by the screams of Beatlemania, and they were ultimately overwhelmed by the perky power — and sheer numbers — of those who would rather listen to the Beach Boys than discuss the plight of Cuban revolutionary Che Guevara. But the Beats and Folkies never truly went away, they just mutated into new forms which eventually came out in the music and politics of bands like the Byrds and people like Jim Morrison.

In a complete reversal of fortune, the beliefs and politics of the Beats — which had been mocked and ignored at the start of the ’60s — had, by decade’s end, become the prevailing attitude of their generation. By 1969, the Beach Boys (who had ruled the airwaves in the early ’60s) were hopelessly square and out-of-date while Che Guevara’s picture was plastered on posters and t-shirts and proudly pinned to the walls of crash pads and college dorms across the country.

Riots and protests, sit-ins and draft card burnings were as commonplace as sock hops and beach parties had been. And not just on college campuses either. High school and grammar schools also saw their fair share of turbulence too, mostly in the Deep South where the forced busing of school kids was a hot topic.

Leaders were being assassinated.

The President was conducting secret wars in Southeast Asia.

The country was tearing itself apart and the music and the musicians reflected this.

And then sometime around the mid-’70s, things changed. The Vietnam War ended. Nixon was thrown out of office. Rock ‘n’ roll was coming into its own as the dominant force in mainstream culture. The malcontents who, just a few months before, had railed against the Almighty Dollar and the Man realized that they didn’t have to storm the barricades after all; they were given the key to the palace.

And once inside the golden gates they worked to turn the music of a disenfranchised people into the sound of the mainstream — and make a ton of cash in the process. Thanks to bands like Led Zeppelin and Fleetwood Mac, albums now sold in multi-platinum units. Rock ‘n’ roll was Big Business and young entrepreneurs (like David Geffen) were in charge. As rock music grew in power, as a driving force in pop culture, it transformed from a small movement and into an industry (which it what it became by the mid-’70s). The idea of “keeping the faith” and “sticking it to the Man” grew from a rallying cry of the disenfranchised into a marketing ploy.

By the late ’60s the “marketing boys in the backroom” (who merely shifted in age as a younger generation of ‘Hippies’ were brought in to ‘relate to the kids’) used the philosophy and words of the counter-culture to sell them product. The most ludicrous example is the marketing slogan used by Columbia Records in 1968 to promote their catalog. A slew of ads appeared in magazines like Rolling Stone announcing “But the Man Can’t Bust Our Music”. The fact that were the Man (or one of them anyway) didn’t seem to occur to them. Regardless, now that the corporate Big Boys had put a toe into the water the counter-culture was doomed.

Rock ‘n’ Roll Sells the Burgers, Man…

So, here we are today with rock ‘n’ roll, the music once the sound of outcasts and outlaws, being used to flog everything from automobiles to hamburgers.

So? Why does anyone care? Why should you care?

People don’t get upset when some country music star hawks Ford trucks on TV. But rock ‘n’ roll is still rebel music (even if in image only these days). Since its inception, rock music fans have held their heroes to a higher degree of responsibility and consistently struggled with the paradox of “selling out”. For to be considered “authentic”, rock music must keep a certain distance from the establishment and its constructs; however certain compromises must be made in order to become successful and to make music available to the public. This dilemma has created friction between musicians and fans, with some bands going to great lengths to avoid the appearance of selling out.

Some artists have resisted Madison Avenue (Neil Young, Bruce Springsteen, Tom Waits to name a few), but the paradox of rock ‘n’ roll is, despite all its anti-establishment rants, it has never been completely immune to the corporate lure. Selling out has always been less a question of If than of When. Back to the original example: Despite Jim Morrison’s passionate position, he ultimately lost his fight with the band. While Buick never created the “Let Buick Light Your Fire” TV commercials as planned, they did run a similar-sounding print campaign for the Buick GS 455, in 1970 (which only goes to show how out of touch the automakers were to try and bask in the reflected glory of a three-year old song).

To tweak the band for having even considered working with the Man, Morrison added a little ‘jingle’ of his own to their 1969 hit “Touch Me”. At the very end of the song you can make out Jimbo singing “stronger than dirt”. That was the slogan for Ajax cleaner. But the Doors were by no means the first rockers to nuzzle up to advertisers…

In 1954, Elvis Presley did his one and only endorsement, a radio jingle for Southern-Maid Donuts, as part of his contract with the Louisiana Hayride show. In 1963, the Rolling Stones cut a jingle for Rice Krispies cereal. Not only did they record it, they wrote it (for the record it’s called “Wake Up in the Morning” and it’s really a pretty good tune). It stands as the only song they ever released that was written by the late Brian Jones. (Interestingly, the writing credits actually read Jones/J.W. Thompson. J.W. Thompson is J. Walter Thompson, the advertising agency behind the commercial, surely the first, and last, time an anonymous copywriter at an ad agency shared writing credit on a Rolling Stones song.)

During the peak of “First American Visit Beatlemania” it was not uncommon at all for the Fabs to endorse local radio stations, even going so far as to quote their tag lines on air and wear promotional shirts, and George and John inadvertently doing an advert for Marlboro cigarettes. Of course, these were done in innocence — they weren’t really endorsing anything per se, just having fun.

While the love affair between rock and revenue has not always been smooth (there was a period when the corporate world was scared of its “sex, drugs and rock ‘n’ roll” stance) it has remained steadfast and true to the point where, today, it’s a mutual admiration society.

Coca-Cola was one of the original leaders of the trend. Roy Orbison did a Coke jingle (as did the Supremes, Jay and the Americans, the Moody Blues, Jan and Dean, Petula Clark, and Ray Charles). And when the decade ended with what was perhaps the most successful television ad campaign for Coca-Cola, the so-called “Hilltop” commercial featuring the song “I’d Like to Buy the World a Coke” — which actually became a radio hit for the New Seekers — the line between art and commerce was becoming as cloudy as Roy’s vision. And while we’re on the jingle bell rock theme it bears mentioning that (although they were hardly rock ‘n’ roll) the Carpenters’ big hit, “We’ve Only Just Begun”, was originally written by Paul Williams and Roger Nichols as a radio jingle for a California bank.

Also, Tony Asher, Brian Wilson’s lyricist for the legendary Pet Sounds album, was originally a jingle writer. Warren Zevon got his start as a jingle writer for Chevrolet, Hunt’s ketchup and Boone’s Farm wine. And, as every child knows, Barry Manilow was the writer of the infamous “You Deserve a Break Today” jingle for McDonald’s. Harry Nilsson, the Beatle’s favorite singer, started out singing jingles, his most famous being for Ban Deodorant. Iron Butterfly did one for them too. Blurring the already splotchy line between art and advert yet even more, Nilsson also recorded a commercial for himself, a song of the flip side of his “Down to the Valley” single titled “Buy My Album”.

Things were getting weird indeed.

* * *

Rock ‘n’ roll rose in popularity in the ’50s as a direct response to the stifling popular music of the day which, for the most part, consisted of innocuous ‘pop’ tunes like “How Much Is That Doggie in the Window?” aimed not at the youth but at their parents. Before the rise of the (now infamous) Baby Boomers, youth (soon to be labeled “teenagers”) was merely a short, awkward, stage of growth between childhood and adulthood. It was a stage to get out of as fast as possible, not relish and luxuriate in. The idea that the teen years should be celebrated — and marketed to — was quite new.

Before Elvis, the world of teenagers was a small time affair. Major merchandisers hadn’t yet learned to aim their wares at youth, and so teens were left alone for the most part to wallow in fads and fancies, to which the world of grownups was oblivious. Out of this private world of secret language and signals came a true sub-culture. It was the teen who cared about acne, eye liner, fuzzy pink sweaters and leopard-skin pants.

When Elvis blazed upon the scene in the mid-‘50s, arguably giving birth to rock ‘n’ roll, it had all the trappings of untamed youth banding together to give voice that the old days and old ways were on their way out. Here was a new music, a new attitude, a generation of youth creating their own world by their own “Teen God”. This was, for the most part, complete bullshit. Elvis was an authentic talent all right, but he was hardly the leader of a new youth culture in the sense that he instigated any thing or led anybody anywhere. He took a sound that had been quite common in the rural South, a jump blues created by African Americans that was played on many a porch by many a picker, and made it popular.

Elvis didn’t invent rock ‘n’ roll, nor was he a committed rocker, as was proved by his later music. He was in fact the willing puppet of his handler, “Colonel” Tom Parker, a former circus barker who was at least a generation older than the teens he sold Elvis to, and was more interested in marketing than management or rock ‘n’ roll (he even covered all bases by selling both “I Love Elvis” buttons and “I Hate Elvis” buttons). Parker was not a military colonel, it was an honorary title given to him in 1948 by Governor Jimmie Davis of Louisiana. His pre-Elvis experience included shows called The Great Parker Pony Circus and Tom Parker and His Dancing Turkeys and was a veteran of carnivals, medicine shows and various other entertainment enterprises.

Parker was a man who saw Elvis not unlike the circus freaks he had previously worked with, as a sideshow attraction, a commodity to be sliced and diced, packaged and reshaped to the fans in any manner that made a buck before the fad faded. The fact that the Colonel was able to do the most wretched things imaginable to Elvis’ career over the years — had him star in films that were as interchangeable as they were unworthy, and record crap like “Can’t Rumba in the Back Seat Baby” and yet have Elvis retain any degree of street cred is amazing. And that’s only because no matter what amount of poo was piled atop his persona Elvis was still, at his core, the real deal.

To be fair, the idea that Elvis, or rock ‘n’ roll, was anything but a commodity; a passing fad like the Hula Hoop that could be bought and sold like, well, Hula Hoops, had not yet formulated. It doesn’t matter whether it was Elvis, Ike Turner, Bill Haley or Chuck Berry who first “invented” rock ‘n’ roll, Elvis (well, the Colonel) was the first one to recognize the money that could be made off of the damn thing. In some respects it was Colonel Tom Parker, and not Elvis Presley, who was the true innovator.

Under the Colonel, rock ‘n’ roll and commerce got along splendidly for several years. But once the marketing boys in the backroom woke up to the fact that there was gold in “them thar hillbillies” all bets were off. They began to manufacture their own teen idols geared strictly to make the cash register ring and whether or not they could sing didn’t mean a thing.

They managed to best the Colonel at his own game and after Elvis went into the Army, Chuck Berry went to prison, and Buddy Holly went to rock ‘n’ roll heaven, the plastic pop stars they’d created, like Fabian and Frankie Avalon, took over.

They were then force-fed upon an innocent teen public as this year’s model and, sadly, the teens lapped it up. It didn’t matter to them one bit that their new heroes were about as authentic as Jane Mansfield’s breasts, they were cute and the fan’s simply didn’t know any better. It was at that point that mainstream rock ‘n’ roll went from rebel wild child to sweet painted whore, willing to drop her panties for anyone at any price. And it’s really been the same ever since.

* * *

It’s often thought with the appearance of early ’60s bands like the Beatles and the Rolling Stones that rock ‘n’ roll became more of a movement truly belonging to teens; that they took it out of the hands of the elder image makers and created their own counter-culture. This is, of course, complete bullshit. The Beatles and the Stones — both authentic rock ‘n’ roll talents — were just as carefully packaged and sold to the teenagers as had been Frankie Avalon.

Brian Epstein took the scruffy leather-clad Beatles out of the musty Cavern and put them into suits. Stones manager, Andrew Loog Oldham, created the Stones’ image as the ‘anti-Beatles’ in one fell swoop with the headline “Would You Let Your Sister Go With a Rolling Stone?”

The difference is that these bands (and others) were more in touch with the authentic spirit of rock, and more in control of their own destinies — after all, they’d been the target audience for the plastic pop stars that had come before them and had rejected them wholeheartedly.

Their management too understood the importance of “keeping it real” and, unlike the Colonel, were roughly the same age as the artists they represented. In the case of Oldham he was actually younger than the band. But that’s not to say that they didn’t also understand the importance of a dollar — they were managers after all — and thought nothing of having their bands endorse products or record commercial jingles. The Beatles cut the theme to the radio program “Pop Goes the Beatles” (years later McCartney wrote a song specifically as the theme for a Cilla Black TV series, Step Inside Love) and, as previously stated, the Stones cut a jingle for Rice Krispies.

What’s interesting about the Rice Krispies jingle is that the Stones did it under the stipulation that it never be reveled who the band playing it was. Whether that was because they didn’t want to be seen as shilling for the Man, or because they didn’t want to be associated with the song (an R&B workout which really isn’t any worse than a lot of songs on their first few LPs) we don’t know. Even the great avatar of anti-consumer-culture, Frank Zappa, did a magazine ad in 1967 for Hagstrom guitars.

The Who Break Out…

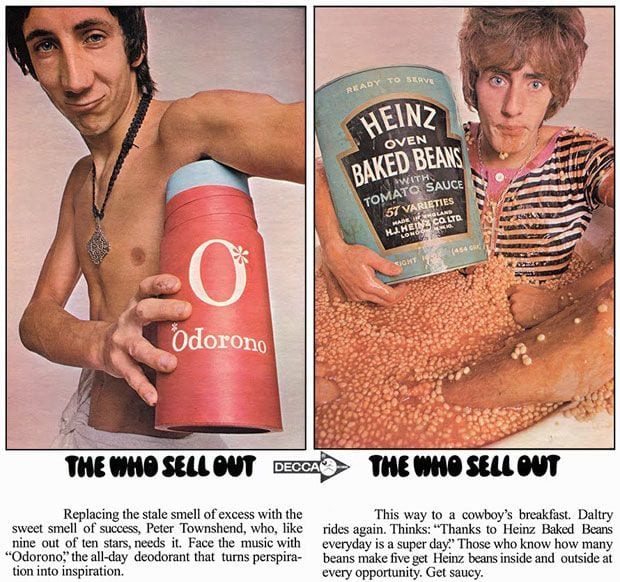

In 1967, the Who were so keen to break through that they even recorded an entire LP, The Who Sell Out, where they interspersed their songs with original jingles for Rotosound guitar strings, Coca-Cola, the Speakeasy and Jaguar cars, among others. Of course, being the Who it was a brilliant record, done with great style and wit as a tongue-in-cheek Pop Art piece. But, as they themselves have said, the jingles were not recorded as spoof; they were serious attempts to arouse the interest of corporate sponsors to off-set recording and touring costs.

The idea had come from Who manager Chris Stamp (brother of actor Terence) who tried to interest advertisers in paying for the adverts recorded by the Who on the record but, with only 50,000 copies of the album expected to be printed, none of the companies would buy. The idea was revived with less artistic-success in 1986 by a band called Sigue Sigue Sputnik. They actually managed to sell commercial space on their LP, Flaunt It, to Tempo Magazine, Network 21 and Studio Line by Loreal.

The Who (or rather, Chris Stamp) was on to something. They were just ahead of their time, and not yet quite popular enough to make it work. That is what lies at the very heart of what selling out is all about. In order to sell out you have to have something worth buying and, bluntly put, for corporations, that means major acts on major labels with major hits. It isn’t a question of talent; it is a question of popularity. (Interestingly, this has proved less and less true since the ’90s as virtually unknown or forgotten artists and their songs have actually broken in the mainstream market through their use in commercials.)

And the very act of inking a deal with a major record company is, in itself, a sell out of sorts.

Signing with a large label gets you a lot of money and a lot of exposure, but it can also carry with it some hidden dangers to the ‘ol’ street cred’ as some musicians in the ’60s learned when it was discovered that two of the world’s biggest labels, Decca and EMI Records, the homes of the Stones and the Beatles respectively, were heavily involved in the production of electronic equipment for the huge munitions company Armscor, during the Vietnam War.

So while the Beatles were out singing “All You Need Is Love”, their parent record company (EMI) was helping airplanes more accurately bomb Vietnamese villages. Even non-controversial singer Tom Jones (who was on Decca) was so upset that he was compelled to make a statement. He released the LP, A-Tom-ic Jones, featuring the sex bomb gyrating in front of a giant mushroom cloud.

So, what’s a poor boy to do (as Mick Jagger once asked in song) when confronted with the realization that you sold out without even meaning to, that your image as a rock rebel has been compromised because your record company didn’t tell you that they were involved in the munitions industry. You go to an anti-Vietnam rally. But when Mick arrived at the 1968 anti-Vietnam War demonstration in London’s Grosvenor Square, he did so in a sleek, expensive car.

And although he sang about going down “to the demonstration” to get his “fair share of abuse” when the tear gas started pumping and the bottles started flying he was back in that sleek motorcar and on his way home before you could say “Jumping Jack Flash”. But all was not lost, he did manage to turn the experience into not one, but two top-selling songs (“Street Fighting Man” and “You Can’t Always Get What You Want”) which helped repair his credibility, and also made him a lot of jack, Jack.

But is it wrong to turn a political hot potato into a hit record? When did the idea of being a rich, successful rock star become something to hide anyway?

Until the late ’60s, when the whole idea of revolution and anti-materialism was conceived, there was no shame in pop stars making money. Gallons of ink would be spilled in the major music magazines of the day gushing on and on about so-and-so’s new sports car, their gadget-ridden luxury apartment, and their beautiful model/actress/whatever girlfriends. Thousands of photo exposes were taken of rock stars (such as the Beatles and the Stones) attending gala luncheons to commemorate their having sold x-thousand units of their LP.

The rockers were seen smoking big fat cigars, sloshing back Champagne, chumming it up with politicians and publishers… wagging it up with some of the biggest wigs in the recording industry.

Some of them were awarded medals from the Queen. Others were on a first name basis with the Prime Minister. The stars hung out at the biggest and most exclusive night clubs, drank for free, drove Bentley’s into swimming pools, starred in movies, they had affairs with starlets…

And then one day it all changed. Suddenly Hipsters were out and Hippies were in. Cosmic consciousness was hot and commerce was not. The new Left was right, and the Right was wrong. Knowingly or not, a bond was created between artist and audience, a sense that it was Us against Them and a lot of bands were caught in the crossfire. Suddenly pop became rock and hit singles (or “product”) were less important than creating “art” and making “a statement”.

Some bands fell easily into the new way of thinking (the Beatles, Pink Floyd, the Who), others were less successful with it (the Hollies, the Beach Boys, the Rolling Stones), while still others knew enough to realize that it was good business to at least give lip service to it and so donned their Nehru jackets and paisley print pants and bided their time until the fad passed (the Association, the Four Seasons, Paul Revere and the Raiders).

So where did this whole concept of selling out come from?

California, of course.

* * *

While no one person or band can be absolutely credited with the idea of selling out, there is a lot of evidence to suggest that it first took hold in the earliest days of the San Francisco music scene. Before San Francisco, New York had been the place where everything happened. It had been the home of the Brill Building, the fabled ‘music factory’ where songwriters like Carole King, Gerry Goffin, Barry Mann and Cynthia Weil sat in office cubicles churning out hit songs for everyone from the Righteous Brothers to the Shangri-Las.

But it was also the home of the Greenwich Village Beatniks and the folk scene, including Bob Dylan and Peter, Paul and Mary, artists who felt a higher obligation to use music as a political tool. New York was also the on-again-off-again home of record producer Phil Spector.

Although he first made his name in New York as a member of the Teddy Bears, and as the producer of hits by the Crystals (such as “He’s a Rebel”), by the early ’60s Spector had returned again to Los Angeles. He was at the peak of his fame and his success showed those back in New York that “California was the place to be”; that it had a growing and productive music scene, a fact that was underlined by the popular surf sound of the Beach Boys and Jan and Dean. Slowly the cream of Manhattan’s musicians, intrigued by Spector’s success and having grown tired of New York’s brutal winters, moved west. It wasn’t too very long before the trickle became a great flood.

John Phillips, later of the Mamas and the Papas and a seminal figure in the history of rock ‘n’ roll, recalls that it was all happening in California by 1964. Fellow band mate “Mama” Cass had already moved there from New York and that by the time Phillips, wife Michelle and Denny Doherty, returned to Manhattan after a stint in St. Thomas in the Virgin Islands (where they lounged around on the sand, smoked pot, swam, and perfected their harmonies while John worked on some songs like good Hippes) they discovered that all of their boho music friends had already headed to Hollywood.

The great exodus west had begun. New places and faces invigorated the musicians and the music. Minds and morals loosened and drugs began to proliferate freely. Nowhere was this more true than in San Francisco, the city by the bay that has always prided itself on being the wildest in the wild west; a place where notorious (but harmless) loonies like “Emperor” Joshua Norton (a bankrupt British merchant in the 1800s who went mad and declared himself Emperor of the US) had been treated as seriously as their own elected politicians.

It was a broad-minded city that tolerated eccentrics, homosexuals, musicians and new ways of thinking. Encouraged it even. It eventually became the stomping ground for bands like the Grateful Dead, Jefferson Airplane, Janis Joplin, Moby Grape, Quicksilver, Country Joe and the Fish, and many other lesser-known but amazingly talented bands. And just about all of whom owe their success to a legendary, nearly-forgotten, acid-rock-western band called the Charlatans.

The seeds of the San Francisco music scene were first planted in 1965 in Virginia City, a small western Nevada town. It was there that Charlatans put on dance concerts at a dive called the Red Dog Saloon. Psychedelic posters celebrating their shows at the Red Dog began appearing in San Francisco and almost overnight folks started showing up at the saloon to find a happening music scene, one which soon spread west to San Francisco’s Haight-Ashbury district.

With the new music came new attitudes, fueled by mind-expanding drugs like LSD (which was still legal) that de-emphasized the importance of ego, Eastern philosophy that taught harmony and peace with the universe, and groupies that showed sex could be free and fun with none of the trappings of marriage that ‘straight society’ brought.

Everybody was happy — at least until the eventual rot set in — and in their happiness they saw all they had and decided ‘the best things in life were free so who needs money?’ The vibe was shared by fans too, and they saw all the ‘non-enlightened’ rock stars — their heroes as well as their brothers in ‘the cause’ — trapped, trying to measure their success by the Man’s rules: fancy cars, groovy apartments, and the accumulation of money. They saw them pawning their talents for 30 pieces of silver, thoughtlessly creating ‘product’ instead of the art they were capable of. Those musicians who saw the light got a pardon, but those who did not were called out and branded with the two words that spelled expulsion from the magical garden: Sell out.

Of course, ‘sell out’ was a relative term. Was it selling out to hawk the glittery beads and bangles of Hippiedom to gawking tourists at Haight-Ashbury head shops? Or was it simply a way to make a few dollars in order to support themselves without having to succumb to getting a straight job? Were they truly creating a new society, a counter-culture, based on freedom and love, or merely extending their adolescence? The touristic influx that accompanied the highly-publicized San Francisco Summer of Love (helped by the 7 July 1967 issue of Time magazine cover story: ‘The Hippies: The Philosophy of a Subculture’) did nothing to intensify counter-culture. In fact by the time Hippiedom became commercialized, mid-late 1967, being a Hippie had lost its real purpose.

Hippie society was being co-opted by the Man, so on 6 October 1967, dozens of mourners gathered in the panhandle of Golden Gate Park in San Francisco to mark the Death of Hippie, an imaginary character killed off by overexposure and rampant commercialism. A broadside distributed at the event stated, “H/Ashbury was portioned to us by Media-Police and the tourists came to the Zoo to see the captive animals and we growled fiercely behind the bars we accepted and now we are no longer hippies and never were.”

The mock funeral celebrated not the end of ideals and beliefs but hippie commercialism and its ultimate core site, the Haight-Ashbury. It was a commendable idea, but they didn’t really kill off the Hippie so much as wash their hands of things. There was a still lot of money to be made off of the counter-culture, and a lot of enterprising young people saw no reason why the Man had to be the only one enjoying the spoils. “Beatniks are out to make it rich,” Donovan had warned us in “Season of the Witch”. That was soon to become a prophesy.

Woodstock Was the Man Too…

In the summer of 1969 several hundred thousand people gathered on Max Yasgur’s farm in upstate New York to listen to a little music. Woodstock Ventures, the promoters of the counterculture’s biggest bash (it ultimately cost more than $2.4 million) was sponsored by four very different, and very young, men: John Roberts, Joel Rosenman, Artie Kornfeld and Michael Lang. The oldest of the four was 26. John Roberts supplied the money. He was heir to a drugstore and toothpaste manufacturing fortune. He had a multimillion-dollar trust fund, a University of Pennsylvania degree and a lieutenant’s commission in the Army.

He was the Man.

They all hoped to see a tidy profit — after all, the cream of ’60s rock was scheduled to attend: Janis Joplin, Creedence Clearwater Revival, the Who, Jimi Hendrix… Abbie Hoffman, the head of the Yippies, an irreverent left-wing quasi-political organization spawned from the Death of Hippie movement, wanted the money to fund various community projects, including New York City storefronts they rented to shelter runaways and defense funds they established for the “politically oppressed”. The large majority of music fans wanted the event to be free. The promoters were selling out, they cried, trying to make bread off of “their music, man”.

Days before the festival, Hoffman and his lieutenant, Paul Krassner, mimeographed thousands of flyers urging festival-goers not to pay. Of course, that issue became moot as soon as the fence went down which they did almost immediately after the festival opened on Friday. On Saturday night, Janis Joplin, the Who and the Grateful Dead refused to play. Their managers wanted cash.

In advance.

Woodstock Ventures feared the fans would riot if the stage was empty so they pleaded with Charlie Prince, the manager of the White Lake branch of Sullivan County National Bank, to put up the money. Peace and love and a cashier’s check, man…

* * *

It’s convenient to put ‘selling out’ in a box marked ‘Relics from the 1960s’, but it doesn’t stop with Woodstock Nation. The accusation of selling out is still often made against punk bands who sign to major labels, since punk too has a cultural tradition of independence and doing it yourself.

Punk also has a cultural tradition of rejecting not only authority, but also the previous generations of Hippie music. Similarly, the sell out cry is often heard in the indie rock and metal communities which, like punk, have a tradition of mainstream rejection and/or anti-consumerism. Metallica is perhaps metal’s most famous supposed sellout. On the other hand (and there’s always the other hand), Metallica brought metal to the mass audience…

Nirvana did a great job of anti-sellout by writing a hit song about a deodorant, “Smells Like Teen Spirit”, and never cashing-in on it, although the Mennen Company, which produced the deodorant, wouldn’t say whether the song caused sales to spike, but six months after the single debuted, Colgate bought the company for $670 million.

Of the older crowd, Bob Dylan too outraged folk music purists by, in their view, selling out their favorite music for rock ‘n’ roll in 1965, at the Newport Folk Festival. However, Dylan has changed direction repeatedly throughout his career, always gone his own way — something made blindingly obvious in the ’90s when Bob licensed his music for a commercial. No doubt all the folk purists from Newport smiled and muttered “I told you so” when a television commercial for the Bank of Montreal came on accompanied by “The Times They Are A-Changin’” on the soundtrack.

And again, in 2003, “His Bobness” caused heads to swivel when he went so far as to actually in a commercial for Victoria’s Secret, singing “Love Sick”. Is this selling out, or is it simply an older artist trying to reach his audience, utilizing the medium in a new way? I’m not sure, but Bob did it again when he actually starred in a TV commercial for Cadillac in 2007.

After all, in this new Age of Acquisition, where only three or four major conglomerates control what is played on commercial radio, it’s a real struggle for older rockers to remind the world that they still exist. Part of the problem (especially in Dylan’s case) is that it’s all so confusing to know what to think. On the one hand you’ve got the man who wrote “money doesn’t talk, it swears” and “don’t follow leaders, watch parking meters”, while on the other hand Dylan is quoted as saying in a 1965 interview that the only product that might tempt him to sell out was “ladies undergarments”. (Hmm, maybe the Victoria’s Secret thing isn’t so weird after all…)

Which statements did he believe?

Any of them?

The floodgates to the all-out rock ‘n’ roll sell out opened up in 1981, when the Stones inked a deal with Jovan cologne to sponsor their 81-82 world tour. Since then, Led Zeppelin has endorsed Cadillac (Rock ‘n’ Roll), Iggy Pop (“Lust for Life” for Royal Caribbean Cruise Lines), and Ringo Starr appeared (with three of the Monkees) in a Pizza Hut commercial and had a tour sponsored by Century 21 Real Estate. In return for the sponsorship, Starr appeared in one of the mega-firm’s TV commercials and chatted on its website. “When we were all 20, we were really anti-establishment,” Starr is quoted as saying. “Now,” he says of corporate tie-ins, “it’s part of the business.” (Ringo also did commercials for Charles Schwab and Sun Country Classic wine coolers, to name but two others.)

It’s easy to dismiss this because, well, it’s Ringo — but when his Beatle band mate, Paul McCartney, agrees and says that he’s “less disturbed” by commercial use of Beatle music than he used to be then it gets sort of disheartening. But, less we forget, as owner of Buddy Holly’s music catalog, Paul is responsible for the licensing of Buddy’s music for advertising (although he insists he does only at the request of the widow Holly).

Perhaps the biggest shock of all was when Yoko Ono Lennon allowed Absolut Vodka to parody the infamous and controversial Lennon/Ono Two Virgins LP cover for an ad. (So have Bowie and the Velvet Underground, by the way.) How far have we come when an LP cover that was deemed so pornographic that it had to be sold in a brown bag is now displayed in the pages of a glossy magazine? Is that even progress? What’s next, Lennon’s Power to the People as the jingle for the electric company?

Contrary as ever, the late George Harrison said it best in 1987: “If (this commercialism) is allowed to happen, every Beatles song ever recorded is going to be advertising women’s underwear and sausages. We’ve got to put a stop to it in order to set a precedent. Otherwise it’s going to be a free-for-all. It’s one thing you’re dead, but we’re still around! They don’t have any respect for the fact that we wrote and recorded those songs, and it was our lives.” George was right. The Man’s got absolutely no respect for that sort of thing at all.

Then there’s the flip side, cases where the rock-and-ads marriage didn’t work out well at all. Madonna’s aborted “Like a Prayer” commercial for Pepsi, which aired less than a handful of times, fell apart after her controversial video for the same song showed her cavorting in front of burning crosses and featured a somewhat erotic encounter with a black Christ (although the only thing the commercial and the video shared was the music).

And we all remember Nike’s oops-a-daisy campaign featuring the Beatles song “Revolution”, although that was merely a mistake about what rights they had purchased. The late Michael Jackson, who controlled the music of Lennon and McCartney, had only allowed the use of the song itself, not the use of the Beatles themselves singing it.

And then there’s “Poopgate”, the little-remembered Huggie’s diaper commercial that appeared on US television in the early ’80s. It featured the Dave Clark 5 singing “Glad All Over” while a baby cooed and giggled on screen and the announcer told us how new Huggie’s kept baby drier than ever. The fact that the company didn’t bother to get permission at all (assuming, I suppose, that Dave Clark was dead and/or didn’t care) is mind-boggling. Turns out that they were wrong. Dave Clark was not only alive, he was the head of a large British media company and owned all the rights to the DC5 catalog. The poop promptly hit the fan and the commercial was pulled.

Since 1981 the litany of rockers to bow to Madison Avenue is long and varied, including such acts as:

The Kinks (“Picture Book” for Hewlett-Packard), the Hollies (“Bus Stop” for JCPenney), the Rolling Stones (“Start Me Up” for Microsoft, “She’s a Rainbow” for Apple), the Beatles (“Help” for GTE and for Lincoln-Mercury, “Taxman” for H&R Block, “When I’m 64” for Allstate, “Come Together” for Nortel, “Getting Better” for Phillips), Suzanne Vega (“Tom’s Diner” for Nissan), James Brown (“Hot Pants” for Planters), Harry Nilsson (“Everybody’s Talkin’” for Wrigley’s), Queen (“I’m in Love with My Car” for Jaguar), Janis Jopin (“Mercedes Benz” for Mercedes Benz), Nico (“These Days” for KMart), Canned Heat (“Let’s Work Together” for Target), Jethro Tull (“Thick as a Brick” for Nissan), Roy Orbison (“You Got It” for Target), David Bowie (“Heroes” for FTD), Donovan (“Mellow Yellow” for the Gap), the Beach Boys (“Fun, Fun, Fun” for Carnival Cruise Lines), Van Morrison (“Crazy Love” for American Express), Elvis Presley (A Little Less Conversation for Nike), Jimi Hendrix (Purple Haze for Pepsi), the Ramones (Blitzkrieg Bop for Nissan), Sam Philips (I Need Love for Ralph Lauren), the Guess Who (“American Woman” for Nike), T. Rex (“20th Century Boy” for Mitsubishi), the Sex Pistols (“Anarchy in the UK” for Nike), the Who (“Overture From Tommy” for Clarinex, “Won’t Get Fooled Again” for Nissan, “Bargain” for Nissan, “Baba O’Reily” for Nissan), Cream (“White Room” for Apple, “I Feel Free” for Hyundai), Cat Stevens (“The Wind” for Timberland), the Buzzcoks (“What Do I Get” for Toyota), Steve Miller Band (“Fly Like an Eagle” for the US Postal Service), Marianne Faithfull (“Kissin’ Time” for Sony Ericsson), Stereolab (“Fiery Yellow” for Volkswagon), Creedence Clearwater Revival (“Fortunate Son” for Wrangler), the Smiths (“How Soon Is Now” for Nissan), Madness (“It Must Be Love” for Hunt’s) Iggy Pop (“Real Wild Child” for FTD, “The Passenger” for Guiness), Blur (“Song 2” for Mercedes Benz), AC/DC (“Back in Black” for the Gap) and…

…last but not least…

…John Lydon.

Granted, the commercials are pretty funny and it’s true that John has always followed his own muse with a stiff middle finger pointing the way. He’s been making the shift away from angry young punk (which he probably never, really, was) to eccentric old geezer for some few years now — in fact he’s starting to resemble another great British eccentric (dare I say it: his old nemesis, the late Malcolm McLaren — but… really John? Butter? Really? (To quote the Great Man himself: “Ever get the feeling you’ve been cheated?”)

But it’s wrong to always wag a finger at the artists. Many times they don’t own the publishing to these songs (the late Michael Jackson owned the Lennon/McCartney catalog, former Stones manager Allen Klein the Jagger/Richards songbook up-to 1970), or in some cases the performance rights.

Some artists are surprised to find themselves hawking underwear as you are, but there’s little they can do about it. They already made their deal with the Man. Some bands, like They Might Be Giants, decide to write original jingles (as they have for Dunkin’ Donuts rather than have other songs appropriated while others end-up defending themselves from cries of ‘sell out’ when they had nothing to do with it at all.

In 1988, Tom Waits filed a lawsuit against Frito-Lay claiming “voice misappropriation” for having a sound-alike record a Doritos jingle that sounded a lot like a Tom Waits song (years later he did it again against Audi/Spain and General Motors — I’m guessing Tom’s never heard the Waitsianesque jingle for David’s Bridal or the growly Tom-like voice-over for Butcher’s Blend dog food). And then when you throw in a band like Gomez masquerading as the Beatles (singing the original “Getting Better” commercials for Philips — you’ve got some really weird kind of cannibalism going on; a mad cow of rock ‘n’ roll.

Even underground cult faves, like the late Nick Drake for Volkswagon), who never had any real degree of commercial success while alive can find themselves as pitchmen. Although it’s hard to begrudge someone like Drake or the Buzzcocks, if only because they never really received the recognition due them, but for others, like Sting (for Jaguar), James Taylor (for MCI), the Stones and the Who, it’s much harder not to wince. And for still others, there’s no real feeling at all. Do we really care that Men at Work licensed “Who Can It Be Now” to KMart? That the Romantics licensed “What I Like About You” to about a zillion different companies? Likewise Katrina and the Waves with “Walking on Sunshine”?

There’s nothing wrong with rock stars enjoying the fat of their fame, but when you hear “Won’t Get Fooled Again” as the soundtrack to four different commercials between breaks during CSI: Miami then clearly there’s something askew.

“People don’t know how to do anything anymore except shop,” Tom Waits complains. “Eventually, all the products will be owned by one company and someone you know will be singing the theme song.” He believes public acceptance of the rock-and-ads marriage is part of a larger trend where consumerism has become religion and increasingly large monopolies serve as God. And all indications are that it will only get worse.

As in the case of older rockers who are still producing records but who have been ignored by radio (except for oldies and classic rock stations) and are frozen out of MTV and VH-1, commercials give them an outlet to fans new and old. And for acts like Elvis Costello, the Smiths, the Replacements, the Buzzcocks, Nirvana and Soundgarden — bands who are considered seminal but who were criminally underplayed on rock radio when they were new and vital — advertising serves as the Great Career Salvation; the Rock ‘n’ Roll Retirement Fund. How long it will be before we’re treated to the White Stripes singing Hello Operator for AT&T, or Elvis Costello crooning “Accidents Will Happen” for Bounty, is anybody’s guess however, Howard Kramer of the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, has made a frightening prediction.

Kramer sees sponsorship and endorsements going much, much further, going so far as to turn live concerts into “more sophisticated versions of Formula I racing events in which the drivers, their cars, their suits and their crews are covered with endorsements.” Kramer says that the only thing that would curb the trend is if the public stopped buying products that used rock music to sell them, and if they boycotted music events, and musicians, that are so saturated with product pitches and signage that they resembled a car race.

Hmmmm…

Hey Jimbo, uh… you still got that sledgehammer, man?