After making a name for himself in B westerns, “Wild Bill” Elliott dropped his wildness and starred as mild-mannered Bill Elliott in a series of five police mysteries for Allied Artists (formerly Monogram). Although these modest pictures are nobody’s idea of lost masterpieces, they’re nice-looking (with some real locations), well-paced, crisply told stories with thoughtful character parts. This must be attributed to Daniel B. and Ellwood Ullman, whom I’d assume are brothers, though I can’t prove it; one or both of them wrote all except the worst one. All five films are now available in one package on demand from Warner Archive.

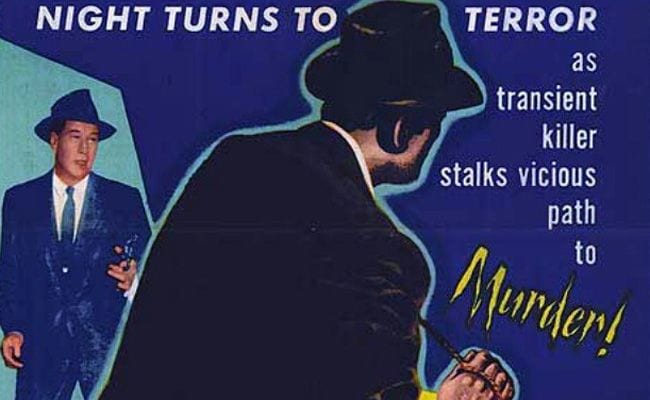

Elliott plays a homicide detective in the Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department; he’s called Lt. Andy Flynn in the first outing and Lt. Andy Doyle thereafter. As of the second film, Don Haggerty shows up as his blander sidekick, Sgt. Mike Duncan. The stories all feature people suspected of murder until the patient, phlegmatic, fedora-and-necktie-wearing lieutenant cracks the case, thus reassuring us that despite tough breaks, happy endings prevail thanks to the intelligence and professionalism of law enforcement.

The hapless individuals feel trapped in common situations from film noir, but those halves of the plot are firmly wrestled into place by the police-procedural half that’s wound around them. It always turns out that the impetuous schlemiels who get themselves in a jam should have trusted the cops instead of getting in their own way. There’s even one movie (the fourth) where the camera looks up towards an avuncular Doyle wagging his finger as he expounds that he’s not sure the suspect is guilty. “We don’t know all the facts!” This isn’t usually what we hear from police characters when it looks open and shut.

Daniel B. Ulllman, a specialist in westerns and TV episodes, wrote and directed Dial Red O (1955), whose most striking element is the detailed and handsome set decoration. You’d think they had a much bigger budget, or else they filmed in real interiors. Keith Larsen plays that uneasy noir standby, a war vet who’s had a nervous breakdown and trouble finding a civilian job. When his wife (Helene Stanley) divorces him, he escapes the hospital and becomes the object of a manhunt after her murder, with everyone assuming he’s a “psycho”. The viewer knows who did it, and the comings and goings around the apartment are well handled, including the nosy neighbor (Jack Kruschen) who writes science fiction. We fear for the hero’s well-being as the circumstances tighten around him.

In a good scene, future director Sam Peckinpah runs the outdoor diner where our hero overhears his description on a motorcycle cop’s radio. This and the next feature, which have the nicest photography, were shot by Ellsworth Fredericks shortly before he did Invasion of the Body Snatchers. The others were shot by the incredibly prolific Harry Neumann, whose final effort was The Wasp Woman.

Sudden Danger (1955), written by both Ullmans and directed by Hubert Cornfield, stars Tom Drake and Beverly Garland in what’s probably the most twisty and noir-ish story. Drake (Judy Garland’s dreamy “boy next door” in Meet Me in St. Louis ) plays a surly, suspicious blind man who may have killed his mother. One nice element is that the viewer doesn’t know whether he’s guilty, although we’ve followed his shoes and seeing-eye dog in the opening sequence toward discovery of the body. Thanks to the delicious performance of next-door battle-axe Minerva Urecal, the police suspect it could be a carefully planned alibi. This is Cornfield’s directorial debut; he’d later do Pressure Point with Sidney Poitier, and The Night of the Following Day with Marlon Brando.

The Ullmans had nought to do with Calling Homicide (1956), written and directed by Edward Bernds. (Bernds worked with Elwood Ullman on Three Stooges and Bowery Boys films, which is another matter entirely.) The whodunit aspect, centered on a modeling school, is both obvious and ridiculous, with one laughable scene of public murder just as a drunk is about to bellow out the name of the guilty party.

This is the only entry to exploit the Hollywood angle; we even visit a movie studio in a nicely framed scene that respects people who plug away on B pictures. The plot has the earliest example I can recall of the trope where somebody gets in a car and it blows up (just offscreen, keeping the budget in mind)–a device soon to be in every TV crime show many times over. If it’s original here, that’s a minor claim to fame; if not, somebody else will just have to research it.

Paul Landres directs Chain of Evidence (1957), starring Jimmy Lydon as the most self-destructive schnook of the series. He’s already been in jail for assault, and he keeps asserting that the guy had it coming. When we see that the guy is tall, sneering, scar-faced Timothy Carey, we believe it. Our pigeon finds himself enmeshed in a femme-fatale triangle out of James M. Cain, here borrowed for Elwood Ullman’s script. This tale even throws in the amnesia angle, as carefully explained by psychiatrist Dabbs Greer.

Elwood collaborated with Albert Band on Footsteps in the Night (1957), directed by Jean Yarbrough. The set-up here is ingenious, as gambling addict Douglas Dick discovers the corpse of his friendly penny-pinching neighbor (Robert Shayne) in the living room during the time he went to the kitchen for a drink. Talk about open and shut, but Doyle invents a theory that could have come out of some twisty novelist’s mind and goes about proving it.

Doyle declares that one must be a judge of character, and he just has a feeling that our excitable hero with mental issues (the third in the series!) didn’t strangle the victim with electrical cable. Eleanore Tannin is the worried girlfriend, and James Flavin is the glad-handing, big-talking out-of-towner who’s key to the murder. This one climaxes in a big ill-advised shoot-out in which, miraculously, nobody gets killed.

So some stories are whodunits and some aren’t, and some are more plausible than others. All are presented and enacted with professionalism and the inevitable sense of 1950s Los Angeles that comes in low-rent crime films of that time and place, and all are at least highly watchable examples of B-pictures that run just over an hour. They make you think Elliott might just as well have starred in a Dragnet-type TV show, and he’d have been exactly the homicide cop you’d want when you get yourself arrested, you poor dumb sap.