“Our procedure has been always haunted by the ghost of the innocent man convicted. It is an unreal dream.”

— Justice Learned Hand, 1923

With this quote opens a documentary that explores a terrifying error in the American justice system. Named for Hand’s quote, An Unreal Dream does more than just question the power of the law. It embarks on a journey through the pain, torment, and ultimate salvation of a man who spent 25 years in prison for a crime he did not commit.

On 12 August 1986 Michael Morton celebrated his 36th birthday. He considers this day, as simple and common as it was, to be the happiest of his life. He was in love with his wife, Christine, and their three-year-old son Eric was finally doing well after heart surgery. The family marked the occasion by going out to eat and on their way home Mortonl found himself struck by the normality of it all. The beauty of it. The following morning he went off to work, unaware that the happiest day of his life would be the last for many years to come.

Morton’s wife, Christine Morton, was found dead in their home on 13 August 1986, bludgeoned to death by a blunt object. Morton claimed to be at work at the time of the attack and upon returning home found the scene to be a nightmare, with yellow police tape around the house and police cars everywhere. He asked to see his wife one last time, but was promptly refused by police at the scene.

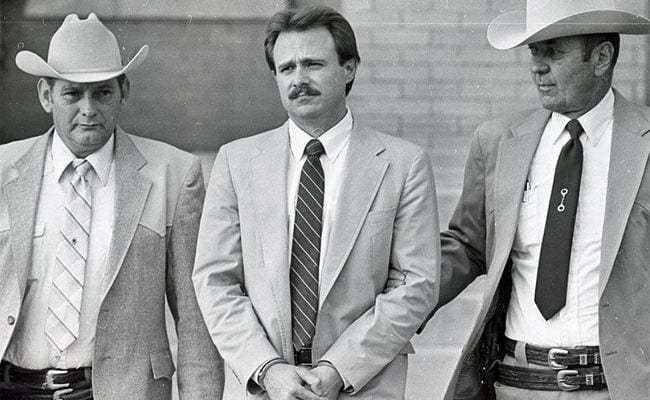

The loss of his wife was devastating, but little did Morton know that things were about to get worse. A few weeks after Christine’s death, Morton was formally charged with her murder. His son was taken away and he was brought in by police, who had no other suspects. He was tried, convicted, and sentenced to life in prison. Morton always maintained his innocence, even refusing parole when he found out that a condition of it would be to admit remorse for his crime. He could not feel remorse for something he did not do, and so for 25 years he remained in prison as his son grew up and away from him. He had nothing but his own thoughts, and he utilized this time as best as he could to mold himself into a more reflective man.

The Innocence Project, an organization dedicated to DNA testing in order to help free wrongly convicted men and women across America, played a big part in Morton’s release, but what the film succeeds in highlighting is not only the scientific limitations in the 1986 case, but the withholding of key evidence that would have had a significant impact on a jury.

An Unreal Dream sets the tone by opening with Morton himself. He is seated in the center of a large, empty courtroom, the same courtroom in which he had been convicted of murder many years earlier. He speaks carefully and concisely, with a great deal of emotion painted across his face and embedded in a pair of rather soulful eyes. The entirety of his interview is conducted in this courtroom, which is likely meant to provoke an emotional response from both Morton and the viewer.

Near the start of the film, a wave of old audio clips plays across images of the courtroom seats and while this proves for rather heavy-handed filmmaking, things soon quiet down and the film develops a steady, even pace. Director Al Reinert is no stranger to the smooth construction of a complicated narrative, and he deftly balances a collection of interviews with archival materials.

There’s nothing more poignant than the way in which Morton discusses his wife. The mention of Christine sparks a light inside of him, and so it seems only natural for him to begin with her. He discusses their life together, how they met, the raising of their son. This display of his love for her at the start of the film only deepens the sense of devastation left in the wake of her death. Morton lost his wife, but by being blamed for her murder he lost everything he had ever known or loved. He never thought he would be convicted for the crime, and the film paints the shocking ease of that conviction in brutally honest strokes.

Perhaps one of the most interesting aspects of the film is the collection of subjects Reinert chooses to include. He compiles testimony from Morton and his lawyers, but also Morton’s son, Eric, now grown, and men who knew Morton in prison, some of whom are still there today. Reinert even interviews a man and a woman who sat on the original jury that convicted Morton, who today feel cheated by the prosecution for the burying of facts.

An Unreal Dream unfolds in a way that is both narratively satisfying and structurally engaging. The story, of course, is central, but the telling of that story manages to live up to the material.

The DVD edition of the film possess a wealth of after-the-fact information, including highlights from the court inquiry and a plea deal hearing for the district attorney who withheld information during Morton’s case. There’s also footage from the film’s premiere at SXSW, where it won the Audience Award, as well as interviews with Morton, his lawyer, and Reinert at this festival itself.

An Unreal Dream is not a flashy film, nor is it, for the most part, a melodramatic one. Instead it prefers to explore Morton’s personal journey, which proves to be more enlightening than one might imagine. His resolve and subsequent freedom are raw, real, and make for one incredible story.