This summer, all eyes are on Brazil and the World Cup. The beauty of the event, football lovers contend, is that it brings people from nations as geographically and culturally disparate as Sweden and Ghana and units them in the spirit of competition. At the same time, the World Cup can unintentionally shine a light on some of the aspects of modern life that most prefer to keep in the dark.

Many soccer clubs have a long history of racial exclusion. Racist chants and gestures, frequently targeted at black players playing in Europe, are disturbingly common (“Racism in football will never be a thing of the past”, by Harry Reekie, CNN, 13 June 2013). And in the heat of a match, the passions of the crowd, the players, and even the referees boil over to a point that can be downright terrifying (“Player stabbed, referee dismembered over soccer quarrel in Brazil”, by Umaro Djau and Ben Brumfield, CNN, 07 July 2013).

But the occasionally ugliness on the field and in the stadium is no match for the sordid things that go on behind the scenes. The Fédération Internationale de Football Association (FIFA), which organizes the World Cup, is widely regarded as a brazenly corrupt body.

Recently, British Prime Minister David Cameron has charged that the bidding process for the 2022 World Cup was “sorted” before voting took place, and an investigation is underway into how football’s governing body chose to stage the 2022 World Cup in Qatar, a country where the average temperature in the summer (when the World Cup is normally held) routinely exceeds 50 °C (120 °F), a fact that has forced FIFA officials to postpone the 2022 cup until the winter of that year.

While the selection of Qatar is highly suspect, Brazil seems like the ideal place for the World Cup. A developing economic power, Brazil is one of the BRIC (Brazil, Russia, India, and China) nations, which economists point to as prime drivers of economic growth in the first decade of the 21st century. Perhaps more importantly, football runs through the blood of Brazilians. The Brazilian national team has won five World Cups (more than any other country) and, in Brazil footballers like Garrincha and Pelé ascend to the status of near gods.

Still, the Brazilian World Cup has not been without controversy. Construction delays, state relocation of poor residents, and massive investment in facilities at the perceived expense of social welfare programs have left many Brazilians questioning the true value of hosting the games. A recent graffiti mural of a starving boy sitting at a table with a lone soccer ball sitting on the plate before him illustrates this complaint. (“Let them eat football: Rio de Janeiro’s anti-World Cup street art”, by Jonathan James, The Guardian, 9 June 2014) But big international events should bring in tourists and raise the status and global awareness of a country, right? Well, not exactly.

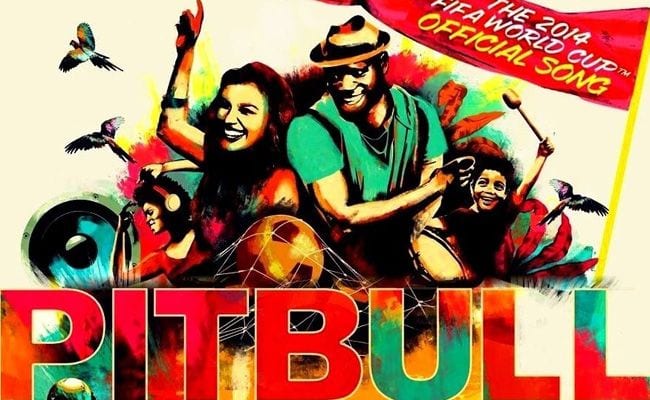

According to the Economist, the high cost of the London and Beijing Olympics have left citizens in those countries wondering if hosting a global sports mega-event really pays off. On the cultural front, the shallow portrayal of rich, diverse cultures in short television snippets between matches don’t necessarily promote a culture. In fact, if the recent release of the 2014 FIFA World Cup theme song, Pitbull’s “We Are One”, featuring Jennifer Lopez and Brazilian singer Claudia Leitte (whose limited contribution makes her inclusion feel obligatory) the World Cup highlights one of the worst trends in a global society: the 20th century desire to boil all culture down to a handful of bland elements and sell it as some sort of triumphant universal human-ness.

It would be hard to find a country more tied in to a genre of music than Brazil is to samba. So it’s no surprise that “We Are One” rides over a rolling samba-like rhythm. But samba represents so much more than a rhythm or even a genre of music. Samba (along with football) is reflective of the idealized oneness of Brazil’s not so distant past.

Originally harassed by police and confined to poorer neighborhoods, samba found its way to national prominence under the rule of dictator Getúlio Vargas. Borrowing from the work of social anthropologist Gilberto Freyre, Vargas sought to promote the notion that all Brazilians, no matter their ethnic makeup, were at least partially racial mixed and therefore a singular people. Samba and soccer were both seen as ways to promote this concept of a monolithic Brazilian identity.

As seemingly well-intentioned as the concept of the “mullato-nation” was, it also gave Vargas a cover, of sorts, to suppress descent as counter-progressive—particularly when coming from factions organized on racial or socio-economic lines. Samba lyrics—once focused on Malandrego, a Brazilian sort of ‘rude boy’—became increasingly censored and the bawdy music of the favelas became the clean, but no less exciting music of the State.

Still, with its joyful, stomping gait and memorable choruses (perfect for bacchanalian sing-a-longs) samba found a national, then international audience. In Brazil the samba assumed a special place in the national consciousness not only through the music’s perceived ability to unite Brazilians in joyous, egalitarian celebration, but also through the samba schools that took root in favelas across the country, which in addition to bringing musical and cultural instruction to the poorest neighborhoods, also provided social and health services to the communities.

One such school, Pracatum, was founded by Carlinhos Brown. A native of the favela Candeal Pequeno, the singer-songwriter/producer was nominated for an Oscar in 2012 for his musical contributions to the animated film Rio. Brown has made a habit of paying tribute to and investing in the Bahia neighborhood he hails from. It’s no wonder that Shakira chose Brown to collaborate with her on the alternative World Cup anthem “La La La”, which many critics and fans have labeled a more appropriate official anthem and video for the World Cup.

If there is a an equivalent to pre-Vargas samba in contemporary Brazil, it’s baile funk, a rough-around-the-edges dance music which was first heard in Brazilian favelas in the ’80s. As a genre, baile funk can’t be separated from its context of loud and lively favela dance parties. The music itself can encompass a wide range of influences, one moment 808-driven Miami bass music, the next traditional instruments and rhythms taken from Brazil’s acrobatic martial art—capoeira.

The genre has seen its share of controversy, however, and baile funk’s perceived relationship with Rio de Janeiro gangs meant the parties were outlawed for a period in the ’90s. Whereas samba was promoted to promote social unity, funk claws at racial and economic fissures. Critics charge that the taboo-smashing lyrics of the genre all too often—like those of its Jamaican cousin dancehall—veer into the misogynistic and grotesque.

Here late baile funk pioneer DJ Amazing Clay gives us an instrumental to get a taste of the deep roots and endless vistas of the music:

There’s more than dance music in Brazil’s hip-hop scene. A number of young artists, inspired by Brazil’s long history of socially conscious music, have used the medium to take on current issues. Here is Criolo with “Não Existe Amor em SP”, which looks at the sometimes bleak, sometimes beautiful landscape of “The Endless City”, São Paulo:

In the coming weeks fans throughout the world will watch the World Cup, and by necessity tune out the contradiction of an event that ostensibly celebrates unity but has a tendency to foment the basest of in-group/out-group racist and nationalist thinking, because we do feel that despite the ugliness, the beautiful game has something to offer the world. This torn sense of loving the idea of the World Cup while hating the realities of the corrupt quasi-state that is FIFA and all it brings to and demands from the countries that host the World Cup is captured in this protest song by Brazilian popular music singer-songwriter Edu Krieger. It is addressed to Brazilian star forward Neymar, to whom Krieger apologizes for his misgivings about the event: