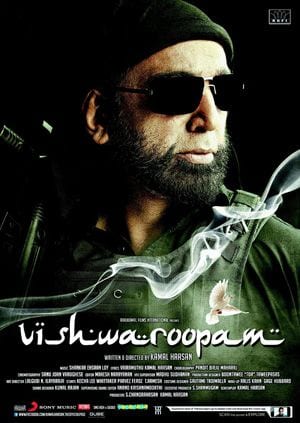

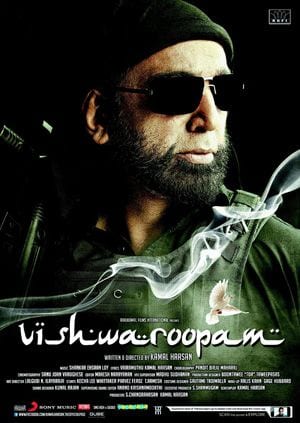

Above: From the poster for Vishwaroopam (2013)

Tamil Cinema’s Action-Masala Genre Goes Global

Since the advent of the talkies, when the visual medium of film acquired an aural element that transformed its techno-teleological appeal and created the institution of cinema in India, the Tamil movie hero has been mired in parochialism. An insular worldview that saw him spend the last 70 years battling a variety of local tyrannies on-screen: feudal landlords, industrialists, fake godmen, gangsters, smugglers, malfeasant cops and bureaucrats, militant feminists, and of course, corrupt politicians [“Rage against the State: Historicizing the ‘Angry Young Man’ in Tamil Cinema”, Kumuthan Maderya, Jump Cut 52 (Summer 2010)].

Since the end of the noughties however, a new kind of action hero exploded on screen via big budget Tamil blockbusters. Seemingly tired of languishing in the shadow of the Bollywood hero who has acquired a global presence, the Tamil hero has started to project himself as an international gendarme battling transnational hazards to peace. His aggressive assertion of Indian power in recent action flicks is represented as a force for global stability, a cinematic synecdoche for Pax Indica. While it’s a grandiose vision consonant with the ambitions of the Tamil film industry to look beyond traditional markets to sell its films, it’s incongruous with actual Indian foreign policy.

Like Hindi-language cinema, now globally known as Bollywood, which began in the colonial Bombay Presidency, Tamil-language cinema had its roots in Madras, the capital of Madras Province, British India. Once Hindi became the lingua franca of postcolonial India, Bollywood became the de facto national film industry and gained greater international presence. Yet, Tamil cinema, now based in Chennai, the capital city of the state of Tamil Nadu, still produces more films than Bollywood, and has also travelled wherever the South Indian diaspora has gone. Southeast Asia, and to a lesser extent, the Middle East have been big overseas markets for Tamil cinema since the ’60s. The Chennai-based film industry is amongst the biggest worldwide, largely because there are more native speakers of Tamil in India alone than there are of many languages worldwide, and Kollywood, Tamil cinema’s trading name, has successfully staved off competition from Hollywood unlike many national cinemas [Dennis Hanlon, “Detachable transnational film style and the global-local dialectic in Mani Ratnam’s Indian adaptations of Amores perros”, Transnational Cinemas 4, 1 (January 2014)].

Nonetheless, aiming to capitalize on intensifying globalization, Kollywood is on the lookout for bigger markets, and larger audiences comparable to what Bollywood has achieved. Over the last three decades, cosmopolitan filmgoers in North America, Western Europe, and Japan have started to embrace Kollywood. To compete effectively with Bollywood, Kollywood must manufacture cultural products to appeal to different target groups and segmented audiences: local filmgoers in Tamil Nadu, a pan-Indian audience through post-production dubbing or multilingual versions (the same movie made imon three different languages sometimes with different casts), overseas Indian communities, and increasingly, foreign audiences across the world. No longer content with being mere import-substitutes to Hollywood and Bollywood, an export-oriented industrial outlook has prompted Kollywood to weave stories with a transcendental appeal, in a bid to surpass Bollywood.

Yet, the severest challenge to Kollywood’s dominant aesthetic form did not come from without. For decades, the action-masala genre (described so since Tamil movies like most of India’s cinemas do not abide by the genre taxonomy of other film cultures) amalgamated song-and-dance numbers, comedy interludes, alongside staples like stunt sequences, fight scenes, extended shootouts, and car chases. Organized around a popular action star with a fanatic fan following as lead, profits were almost guaranteed from this formula.

Because Tamil films began as an ethnic rebellion to North Indian political domination, a site for the assertion of ethno-linguistic nationalism against Hindi, and the celebration of local folk culture [“How a Tamil star is born” Jason Overdorf, Global Post, 3 July 2012], it was unlikely that Hollywood or Bollywood could seriously erode its niche market in Tamil Nadu. The threat came from an unlikely source: what has been referred to as the Tamil “new wave” cinema [“The New Southern Sensation”, Pradeep Sebastian, The Caravan, 1 February 2010]. Circa 2006, an aesthetic revolution began with a series of gritty neo-realist thrillers, ethnographic dramas, and indie black comedies [“After the Cinema of Disgust”, K.Hariharan, OPEN Magazine, 10 August 2013]. The reasons for the emergence of the “new wave” will not be explored here, but all three categories of films gained widespread critical acclaim, financial success, or both.

Seduced by the refreshing “new wave”, the globalized Tamil filmgoer, who was also exposed to transnational film culture, began to expect more from his action films. Soon, a genre purification process began that made the mongrel action-masala films seem insultingly inferior.

Most importantly, the innovations associated with the Tamil “new wave” challenged the hackneyed formulas of hero-centric star-dominated potboilers. The majority audiences rejected movies without a compelling narrative, focused solely on glorifying the cult of the star, which satisfied only their fans. Studios and producers who banked solely on the charismatic presence of the major action stars to sell their films soon found themselves facing a loss. The offbeat low-budget films ended up as winners at the box office. A paradigm shift had taken place in Kollywood. Film critics and intellectuals declared that the larger than life Tamil action hero, who could never perish on screen, was now artistically dead.

In order to resurrect the action-masala genre, and to justify the return of the Tamil action hero, exotic locales, new missions, and new villains tethered to weighty new stories, were found. The regenerative enterprise seems to be to invoke the jingoism of Tamil, and national audiences against real and imagined threats to India from outside, to facilitate the suspension of disbelief critical to the success of the action-masala genre and its heroic excesses.

At the same time, Kollywood had to produce narratives based on global themes resonant with the political consciousness of non-Indian audiences. Whether this particular brand of revived Tamil action-masala genre is merely a coincidental commonality or is indicative of a growing trend is immaterial. Examining these movies as texts offers insight into the collective fears, national aspirations, and Weltanschauung of India’s Tamils vis-à-vis the rest of the global society.

In these fictional narratives, the mission of the Tamil action hero, the coalescing signifier of the films’ various components, is to annihilate antagonists from parts of the world beyond the control and influence of the West. He forestalls the acquisition of Weapons of Mass Destruction (WMDs) by unnamed foreign terrorists in Thaandavam (2012), disrupts illegal genetic engineering by Eastern European scientists in Maattrraan (2012), and polices the Indian Ocean from African pirates and the transnational drug trade in Singam II (2013). His personal struggles are also magnified into an assertion of muscular Indian nationalism in fights and shootouts with Russian arms dealers in Billa II (2012), and a hostage crisis with Sudanese paramilitia in Maryan (2013).

Closer to reality, a Chinese PLA assassin attempts to paralyze India by spreading a contagious virus but is foiled in 7aam Arivu (2011), and he wages a covert war of attrition with Pakistan-sponsored anti-Indian anarchists in Thuppakki (2012). And in the most compelling narrative of all, an Indian secret agent infiltrates Al-Qaeda posing as a jihadi to support NATO operations in Afghanistan in Vishwaroopam (2013). Emanating from the genre’s reorganization, hitherto unseen or uncommon plot devices and conventions have found greater cinematic commitment in Kollywood. There appears to be a genuine interest in faithfully recreating popular genres in the West, like the spy flick, the terrorism thriller, and films about nuclear weapons, to appeal to an international audience.

While on the other hand, the characterization of the weakened West, and the allegorization of confrontations between the Tamil action hero and foreign antagonists [“Foreign baddies muscle into Tamil cinema”, Janani Sampath, The New Indian Express, 1 September 2013] emerge as gimmicks to satisfy pan-Indian audiences. Since in reality India’s foreign policy appears to have limited imagination, the impulse is to elevate the aspiration to the mythic, seeking a vicarious Pax Indica through the action-masala genre.

The novelty is not in the search for foreign locales or a multinational cast, it is in the thematic preoccupation of the genre. Since 1969, Tamil films have on occasion been shot in offshore locations, and Tamil action heroes have sometimes battled foreign-coded henchmen of the principal villain who was invariably South Asian [Selvaraj Velayutham, “The diaspora and the global circulation of Tamil cinema”, Tamil Cinema: The Cultural Politics of India’s Other Film Industry, ed. Selvaraj Velayutham (London: Routledge, 2008)]. However, the regenerated Tamil action-masala genre focuses on macroscopic issues of global concern: the rapidly metastasizing potential of threats, anxieties over lawlessness in the international system, the collapse of hegemonic stability, and fears of a nuclear conflagration, have all generated a sense of impending catastrophe. These films would have us believe that an imminent cataclysm threatens to engulf not just India but also all of humanity, unless the Tamil action hero, the ‘brown messiah’, does something about it.

The top-grossing Tamil film of 2013, the multilingual Vishwaroopam (‘Universal Form’, Dir. Kamalhaasan) released as Vishwaroop in Hindi, crucially illustrates the transformation of the Tamil action-masala genre. The mission of the secret agent Major Wizam Ahmed Kashmiri, belonging to India’s Research and Analysis Wing (RAW) intelligence agency, is to apprehend two of Al-Qaeda’s chief terrorists. In the released instalment, the backstory of Wizam as a double agent who helps Al-Qaeda train jihadis while covertly aiding the US-led NATO forces in Afghanistan search and rescue captured US troops circa 2002, segues into a plot to stop the explosion of dirty bombs in present-day New York city.

In the second half of the Vishwaroopam, Wizam, and his team of RAW agents, and a senior MI6 commander, help the FBI root out sleeper cells in New York city, foiling Al-Qaeda’s latest strike. At the end of Vishwaroopam, Wizam swears not to rest till the more dangerous of the two Al-Qaeda leaders, who have escaped, is dead, setting up to continue the pursuit in a forthcoming sequel. By the end of Vishwaroopam, the multilayered poignancy of its Sanskrit-based title is lucid.

Vishwaroopam intimates to the confluence of Hindu mythology, and atomic theory made famous by the “father of the atomic bomb”, American physicist J. Robert Oppenheimer. Oppenheimer’s adaptation of a quote from the Bhagavad Gita, to describe the effects of an atomic explosion, “Now I am become Death, the destroyer of worlds,” was in effect describing the polycephalic multiarmed avatar of the supreme Hindu deity, Krishna, thereby converging the terrifying image of a wrathful god with the deadliest weapon in human history. The naming of the film more directly refers to the ubiquitous universal threat that radical Islamist terrorism has manifested beyond just the Middle East and South Asia. Finally, the theme song, a paean to the star persona of its lead actor, and the character of Major Wizam, alludes that Vishwaroopam refers to the heroic qualities of the global ‘brown messiah’ who will take on a terrifying form to save humanity.

Because it epitomized spectatorial beliefs and sympathies by indexing actual events, film critic Lenny Rubenstein posits that the spy film was intensely political. Vishwaroopam is no exception, announcing its ambitions with a modified disclaimer at the start of the film that it was a work of fiction not intending to hurt any individual or community. This implies intentionality in bearing more than just coincidental references to actual individuals and developments. More in response to Islamist groups in India pushing for a ban on the film than an apologia on the political message of the film, director-actor Kamalhaasan pulls no punches in this historical fiction. Vishwaroopam directly addresses both ordinary Afghans and Americans as unfortunate victims of NATO intervention in Afghanistan, empathizes with misguided Islamist volunteers for Al-Qaeda’s cause, and spews vitriol at what the film considers to be the warmongers responsible for the conflict: corporate greed in the USA and power-hungry radical Islamist demagogues.

Vishwaroopam reserves its harshest criticism for Pakistan’s Inter-Services Intelligence (ISI) agency as the mercenary interloper, chiefly responsible for the continued political unrest in Afghanistan. The ISI and its double game of being publically allied with NATO but covertly helping Al-Qaeda is exposed in one scene as “the greedy scum that eats in the gutter one day, and in the kitchen the other day.” Facilitated by award-winning cinematography, costume-design, and casting that constructs verisimilitude to war-torn Afghanistan, it draws attention to the troubled country while like most spy films also revealing the national loyalties and fears generated by public and official opinion in India, about the impact that the civil war would have on the rest of South Asia [Lenny Rubenstein, “The Politics of Spy Films”, Cinéaste 9, 3 (Spring 1979)].

Vishwaroopam’s characterization of the Tamil action hero as saviour of both Afghans and Americans, and punisher of threats to global security also reveals the hawkish tendencies some members of the India’s intelligentsia. Kamalhaasan’s grand vision appears to be for India to play a more active role not just in South Asia as an American ally displacing Pakistan, but to be a great power that can project its political and military influence across the world. Hence, a discernibly strident pro-American tone underpins the narrative of Vishwaroopam.

The Moral-Cultural Codes for Tamil Action Heroes

Similarly, in Thaandavam (‘Dance of Death’, Dir. A.L.Vijay), the protagonist Shiva is also a RAW Agent, but this time assassinating threats to Anglo-Indian security and cooperation in London. Agent Shiva’s uses violence to prevent Indian WMDs, from falling into the wrong hands, which is implied to not only seriously cool relations with the United Kingdom, but could also compromise India’s safety. Even after Agent Shiva becomes visually impaired after a bomb blast, he uses echolocation to find the terrorists, their sponsors, and traitors to India, and assassinates them before any further attacks occur.

The intertextuality between Thaandavam and Vishwaroopam lies not only in the titles that allude to Hindu theophany, but also functions to imbue the Tamil action hero with a messianic-nationalist duty. Thaandavam literally refers to the angry dance of the Hindu deity Shiva, from whom the protagonist gets his name. Agent Shiva’s mission to avenge those killed in a London bombing perpetrated by terrorists, and root them out to be executed is portrayed as a Manichean mission. Like Major Wizam in Vishwaroopam, Agent Shiva’s mission in Thaandavam is elevated by these texts to a higher ideological plane that justifies the transmogrification of the Tamil action hero into a punishing deity. He becomes a divinely sanctioned messiah who would use excessive force or all means necessary, to vanquish enemies of India and establish world peace. Acting in the name of global justice rather than a license to kill appears to legitimize his actions.

The dictates of the action-masala genre necessitate displays of pathos by characters in both films. To avoid criticisms of being a mindless action flick, both films take great lengths to present the mission of the ‘brown messiah’ as an ethically just war, waged not just by a surrogate, but an agent of humanity acting against an insidious threat to all of civilized society. In this way, both Thaandavam and Vishwaroopam merge two philosophies in Indian foreign policy into one heroic persona: the older Gandhi-Nehru internationalism based on moral supremacy with Indira Gandhi’s realpolitik undergirded by military predominance. Therefore, the Tamil action hero becomes a symbolic tool to actualize a Pax Indica based on ethical principles and justice backed by force.

Likewise, both Vishwaroopam and Thuppakki share a martial provenance in justifying extralegal actions by the military to confront the scourge of terrorism. In Thuppakki (‘Gun’, Dir. A.R.Murugadoss), Captain Jagdish of the Indian Army’s Defense Intelligence Agency, represents the pinnacle of India’s technological-defensive-strategic capabilities. Unlike Major Wizam who combats terrorism in its bases in South Asia and sleeper cells in the US, Jagdish wipes out sleeper agents in the northern half of his own country. Leading an army team made up of many Indian ethnic groups, Jagdish ingeniously flushes out potential threats to the Indian nation-state, killing them before they are activated. Mumbai city, the Indian economy’s nerve center and the setting for Thuppakki, is sustained by the protection of the Tamil action hero.

Thuppakki

The main antagonist and terrorist mastermind in Thuppakki, bent on balkanizing India, and crippling her economy, is at once familiar and alien: the Kashmiri militant. Unlike other Tamil and Hindi films, such as Roja (Dir. Mani Rathnam, 1992) and Mission Kashmir (Dir. Vidhu Vinod Chopra, 2000), Thuppakki uses various strategies to demonize the Kashmiris as foreign agents orchestrated by anti-Indian paymasters, not as insurgents fighting for the right to self-determination. By unsubtly naming the Kashmiri terrorists as affiliated to the Pakistan-based terrorist group Harkat-ul-Jihad al-Islami, any political sympathies it may invite is drained.

Here. Thuppakki replicates right-wing films like Vallarasu (‘Superpower’, Dir. N.Maharajan, 2000), Keerthi Chakra (‘Medal for an Act of Valour’, Dir. Major Ravi, 2006), and Velayutham (‘Divine Spear’, Dir. M.Raja, 2011) where the terrorist as freedom fighter association is delinked, and the radicalism of the Kashmiri militant is criminalized as a Pakistan organized subversion of India. The militants in Thuppakki are postured as murderous anarchists, who make no authentic references to Islamism or national liberation, thereby justifying Jagdish’s use massive retaliation via extrajudicial murders, torturing suspects, and forced suicides.

The sequence where Jagdish’s team annihilates the sleeper cells is even constructed in the format of a training video with a montage of synchronous multiple frames. An instructional video by the ‘brown messiah’ on how to prevent threats to national security from sleeper cells, so to speak. The self-assured Jagdish ostensibly commanding the operation describes to the viewing audience the entire process, as though advising the international community on how best to deal sleeper cells otherwise impervious to the reach of conventional counter-terrorist procedures. Jagdish’s unconventional methods to eliminate the Kashmiri terrorists are rationalized as necessary in the war against the dehumanized and deideologized mercenary troops of Pakistan or Al-Qaeda.

Singam II

Jingoistic to say the least, the latest action-masala products from Kollywood also make explicit the limitations of the West, exaggerate the threat from rogue states, and situate the unorthodox methods of the Tamil action hero, the synecdoche for India, as the solution to international threats to peace. The murdered senior MI6 commander (an aged James Bond?) in Vishwaroopam, the ritually sacrificed Australian coast guard in Singam II, and the clueless FBI Agents in the former, are fictional constructions of Western ineptitude [“The weakened West”, The Economist, 21st September 2013], which the Tamil action hero must supersede to achieve his mission.

In contrast, the foreign adversary is depicted as a formidable threat, a barbarous villainy unhindered by legal limits, moral paradigms, or ethical concerns. The choice of threats originate from parts of the world where the West has neither the will nor the capacity to enforce international law or establish any influence: Russia, former Soviet Socialist Republics, Sudan, the Horn of Africa, Afghanistan, Pakistan, and China. Here, the Hero’s willingness to transgress international law, sovereignty, violate ethical principles, and escalate violence in excess of what the threat can offer to establish order ultimately accounts for his triumph.

The most astute commentary about the anarchical state of international relations is made in the least gratuitously violent film in the list: Maryan (‘The Immortal’, Dir. Bharatbala). The kidnapping of four Oil and Natural Gas Corporation (ONGC) workers by Sudanese tribesman in 2008 provided the inspiration for the film’s plot, which melodramatized the event through the travails of a single fictional character Maryan Vijayan Joseph. The titular Maryan is a love-struck daredevil fisherman in the southern-most coast of India, who is pushed out of India due to the high uncertainty of income, migrates to work in the oilrigs of Sudan, and gets caught in the maelstrom of the Darfur conflict.

Maryan

Kidnapped by mercenary paramilitia, Maryan’s torment and humiliation at the hands of the paramilitia, and how he escapes from them completes the film’s narrative arch; a messianic monomyth. A recurring leitmotif in Maryan is the contrast between the manageable class and caste related troubles in the idyllic coast of Kanyakumari, Tamil Nadu, and the dangerous world that exists beyond India’s maritime boundaries. A foreshadowing of international lawlessness is made early in the film when Maryan’s friends are shot by the Sri Lankan Navy, re-enacting a problem that continues to plague Indo-Sri Lankan relations [“Sri Lanka Arrests 64 Indian Fishermen”, Ankit Panda, The Diplomat, 25th June 2014].

The bone-dry, arid, and dusty mise en scène in the Sudan sequence in Maryan signifies a post-apocalyptic political landscape, which the Tamil action hero must overcome as part of his heroic journey. Bedlam reigns in the territory where the central authority of the state has collapsed, and the national army no longer holds monopoly over violence. Maryan’s filmmakers have taken great pains to find a desolate desert setting to throw the reluctant Tamil hero into.

Sudan is convincingly staged as a savage world where modernization and development have failed, in which only the fittest survive. A political geography analogous to many parts of the developing world ruined by post-Cold War intrastate wars as retreating superpowers and contracting hegemonic stability destabilized fragile states. Far beyond the hegemony of the West, in Maryan, Darfur represents the hostile wilderness where international law, norms, human rights, and diplomacy, have no reach. Where only the ‘brown messiah’ might have any chance of surviving, and punishing those responsible for perpetrating the atrocities associated with destructured warfare.

In the penultimate scene of the film, the suffering Tamil action hero, escapes from, and kills his hostage taker, thereby completing his heroic journey. Maryan is most unlikely as a ‘brown messiah,’ who nevertheless survives the descent into the hell of genocidal warfare, and returns intact. Maryan’s struggle, takes a leaf from Joseph Campbell’s The Hero with a Thousand Faces (1949) as he reaches “into depths were obscure resistances are overcome, and long lost, forgotten powers are revived, to be made available for the transfiguration of the world.” Finding his way into the coastal regions, where the sea meets Sudanese land, Maryan gathers the strength to fight back against his oppressors, and avenge the death of the other kidnapped oil-workers murdered by the tribesmen.

Earlier, Maryan was helpless to retaliate against what is postured in the film as the state-sponsored terrorism of the Sri Lankan Navy killing innocent Tamil fisherman. Now with the option available, Maryan unleashes retributive justice as an emissary of the civilized world on the Sudanese mercenary, an unknowing instrument in service of Pax Indica. The ideological subtext of Maryan appears to once again vindicate the use of armed force against threats to life and liberty in international affairs where the law of the jungle endures.

If the law of the jungle was the prevalent spirit of current international relations, one blockbuster in the new action-masala genre leaves no doubt as to who is king. Singam II (‘The Lion’ Part II, Dir. Hari, 2013) is the apotheosis of the myth of the ‘brown messiah’. The original Singam (‘The Lion’, 2010) made by the same director and lead star team, was declared a super hit when most of the big budget star vehicles sank without a trace at the box-office in the face of the Tamil “new wave”. The cross-cultural appeal of Singam spawned multiple clones in India’s Bollywood, Kannada, and Bengali language industries. The success of Singam lay not only its projection of an ideal law and order apparatus, effective, efficient, and incorruptible in an India where malfeasance is rife, but also in its fast-paced narrative, plot twists, and thrilling action sequences.

The similarly high-octane narrative of Singam II continues to follow Deputy Superintendent of Police Duraisingam, this time on the supercop’s mission to end the drug smuggling network on the southern most coast of India, propped up by maritime piracy from the Indian Ocean ports on Africa’s east coast. The nexus between politics, business, and the underworld is elaborated in Singam II through the local gangster-politician Bhai, and the business moghul Thangaraj. The rogues’ gallery is complete with a villain who globalizes the narrative, colluding with Bhai and Thangaraj: the Nigerian pirate and international druglord, Danny.

Danny’s character fuses the cold-blooded killers in Thuppakki, with the exotic savages in Maryan, into an antagonist who is callous and brutal. The posturing is conscious because it sets up a showdown between druglord Danny, and supercop Duraisingam, allowing the Tamil action hero to triumph where even the collective actions of Interpol failed. Singam II opens with an Australian coast guard being ritually murdered by Danny on board a ship in the Indian Ocean. After the Caucasian who tried to arrest Danny is disposed off, amidst his shipload of celebrating pirates, Danny declares, “I am the King of the Indian Ocean!” The fan, and the filmgoer would expect quite predictably that Duraisingam would have something to say about this at some point in the narrative. After apprehending Bhai and implicating Thangaraj, Duraisingam pursues Danny all the way to South Africa, teaming up with the law and order officials there to arrest and extradite the pirate.

Markedly different from the desolation of Sudan in Maryan, urbanized South Africa also allows multiple opportunities to display the Tamil action hero’s hypermasculinity. Whether in the planning phases of Operation D named after Danny or the execution of the mission, Duraisingam, the idealized epitome of the Indian Police, a tagline used in the promotional posters and advertisements of the film, is differentiated as physically and mentally superior to his South African counterparts who openly acknowledge this fact. In one action sequence, while in pursuit of Danny and his hoodlums, Duraisingam manages to outpace the South African police who are shown to be in awe of the superhuman prowess of the ‘brown messiah’. These tropes are deliberate because the sacrificed Australian coast guard in the opening scene occupy a similar symbolic position to the South African police officers who cannot catch up with Duraisingam: the weakened West. With only the most perfunctory consideration for western institutions, laws, or procedures, which Singam II fascistically professes as the reason for thriving criminality in the world, Duraisingam hunts for Danny.

In the final fight scene on the Indian Ocean, not dissimilar to that between Captain Jagdish and the Kashmiri terrorists on the high seas in Thuppakki, Duraisingam singlehandedly overcomes Danny and his shipload of pirates. Supercop Duraisingam reinvigorates traditional expectations of heroism, not just as an Indian policeman serving a social purpose to rid Tamil Nadu of anti-national elements, but as an agent of the international community, which wants to end maritime piracy, and the transnational drug trade. The soundtrack accompanying the fight scenes is unrestrained in extra-diegetically eulogizing Duraisingam as an ubermensch. The most overtly racist of the action-masala genre, the Tamil action hero in Singam II is shown to be morally superior to the African, and sharper and tougher than the Caucasian (consciously coded as a white person to trigger postcolonial triumphalism). Rearranging global core-periphery power relations between the West and India, and subverting the white saviour myth Singam II feeds into nationalist fascination with a strong Indian nation-state feared and respected by other nations.

Confused Action-Masala Par Excellence

The action-masala genre even reveals clues as to where the core of Pax Indica will be. There are multiple subtle and obvious references to South Asia as an Indian sphere of influence, where unparalleled hard power, and uncompromising political and economic control, must be asserted. At the end of Singam II, when the Tamil action hero emphatically declares to the defeated Nigerian pirate: “Indians are always King of the Indian Ocean! [Sic]” it is just one instance of cinematic irredentism.

Machismo and ‘trash-talking’ aside, Duraisingam’s unilateral declaration, if it were official, will offend a host of countries sharing the Indian Ocean: Australia, South Africa, Mozambique, Madagascar, Kenya, Somalia, Oman, Myanmar to name a few, and especially Bangladesh, Maldives, Pakistan, and Sri Lanka in South Asia. Maryan’s unilateral reference to himself as the prince of the Indian Ocean, in the eponymously named film, reinforces the irredentist claims of Duraisingam’s impudent rhetoric in Singam II.

Likewise, Wizam’s benevolence towards Afghans in Vishwaroopam who in turn accept the ‘brown messiah’ as one of their own parallels popular pro-India sentiment [“Afghanistan Favors India and Denigrates Pakistan”, Jack Healy and Alissa J. Rubin, The New York Times, 4th October 2011] in contemporary Afghanistan. Afghanistan looks favourably to India for political backing and economic support, compared to its distrust of other foreign intruders. The positive representations of interactions between Wizam and the Afghan locals appears to be symbolized as an inducement for India to continue to extend its influence, supplanting Pakistan and Al-Qaeda presence in the country.

Vishwaroopamuses the iconic figure of Osama Bin Laden as a warning to India against allowing Afghanistan to politically backslide. Osama ‘cameos’ as a character, known as ‘the Sheikh’, not only to authenticate the historical fiction of Vishwaroopam with realist markers, but appears to function as a critique of the blind faith of Al-Qaeda terrorists, who venerate him and risk their lives to protect. In Vishwaroopam’s analysis, the alternative to Indian influence in Afghanistan would be regression into a pariah state ruled by religious fanatics sponsoring jihadist terrorism, as it was under the Taleban. This would be a situation certain to destabilize South Asia and the world [“A Deadly Triangle: Afghanistan, Pakistan, and India”, William Dalrymple, The Brookings Essay, 24th June 2013]. The new Tamil action-masala genre melodramatizes the options facing India: messianic leadership to help stabilize a volatile region, or face the backlash of passive non-interference.

7aam Arivu

Traditionally, India’s geopolitical imperatives were limited to South Asia, but 7aam Arivu (‘Seventh Sense’, Dir. A.R.Murugadoss, 2011) has a farther strategic imagination. In 7aam Arivu, a Chinese assassin Dong Lee, trained in martial arts, hypnosis, and mind control, is sent by China to spread a deadly virus to destroy India. The Chinese in the film call it “Operation Red”, a hint at the low intensity Maoist insurgency in central and eastern India, supposedly sponsored by China. Starting from Chennai, the contagion quickly spreads throughout Tamil Nadu, and the rest of India. In order to stop Dong Lee and the spread of the disease, a group of young Indian scientists, attempt to revive the ancient knowledge of a Tamil monk, who apparently founded the Shaolin School of martial arts, the Bodhidharma. They attempt to do this by retrieving the genetic memory of his only surviving descendent, the protagonist of 7aam Arivu. Of course, the Bodhidharma’s wisdom and martial arts skills are revived in time, and the Chinese assassin succumbs in a kungfu showdown with the ‘brown messiah’ who also has an antidote to the plague. Part documentary, part mythopoeic, part love story, part nationalist propaganda, part science-fiction, part medical thriller, and part martial arts film, 7aam Arivu is the confused action-masala genre par excellence.

Indulging in more than a cursory reference to history, 7aam Arivu is the most neo-traditionalist of the recent films in the Tamil action-masala genre. Using science fiction, and historical fantasy to mask its atavism, it harkens back to antiquity for a political purpose. 7aam Arivu has a specific historiographical agenda to support the construction of the ‘brown messiah’ myth. The narrative commences with a documentary-style introduction to the Bodhidharma, complete with vox populi interviews, screenshots of a Wikipedia page dedicated to him, and other Internet images, showing common knowledge of the monk amongst East Asians unlike the clueless Indians.

While there are competing accounts about the origins of the Bodhidharma, 7aam Arivu, hijacks him for its ideological project, declaring with certitude that he was a Pallava prince. Using digital simulation, a Tamil kingdom from late antiquity is recreated: a utopian world where all men appear to be gold encrusted and god-like in stature, practicing martial arts, as though implying a genealogy from a glorious martial civilization. The prince leaves his kingdom, renouncing all material trappings, becomes a Buddhist monk, the Bodhidharma, and travels to China where he settles. The myth of the ‘brown messiah’ gains tractions when the Bodhidharma fights against marauding bandits, and cures a child of a deadly disease, anticipating a future plot device. Soon the people of China begin to venerate him as a sage when he imparts aesculapian knowledge and begins training them in martial arts, leading to the creation of Shaolin Kungfu.

The rest of the convoluted story continues in the contemporary times where on multiple occasions, the exalted past is compared with a degenerate present. In an important turning point in the narrative, 7aam Arivu makes allusions to recent political history: the marginalization of Tamils in Malaysia, and the oppression of Tamils in Sri Lanka. In this scene, the auteur uses the camera to make the protagonist directly address the audience. The alienation effect associated with the Brechtian strategy instead has an ideological function: to instill a siege mentality among the Tamil audience that they are no different from the Palestinians or Kurds or Roma or Basques, urging them to be boldly assertive.

The extended metaphor of foreign threats to Tamil Nadu, and India in general, conflates conspiratorial themes from three earlier movies. The medical thriller E (Dir. S.P.Jananathan, 2006) where multinational pharmaceutical companies use slum dwellers in Chennai as unwitting guinea pigs for human medical experimentation, Peranmai (‘Hypermasculinity,’ Dir. S.P.Jananathan, 2009) featuring foreign mercenaries trying to stop India’s scientific progress by destroying a space shuttle launch, and the blockbuster Enthiran (‘The Robot’, Dir. S.Shankar, 2010) in which European weapon manufacturers attempt to reprogramme an Indian androhumanoid, the world’s first, into a killer robot for use in warfare. In the diegesis of 7aam Arivu, the discussion of the history of oppression between the characters triggers the transformation of the protagonist from passive citizen to nationalist superego, a ‘brown messiah’, resolved to fight against enemies of the Tamils, and by default, foreign threats to India.

The didactic nature of 7aam Arivu is confirmed in its denouement. Replacing the documentary in the introduction, it ends with a television talk show, where the Tamil action hero, makes a clarion call for Tamils, and Indians to retrieve their heritage, to find the wisdom that would make India great again, and to be a superpower. Preceding the talk show, snapshots of the Tamil action hero are shown, researching to find cures for various untreatable, rapidly metastasizing 21st century diseases around the world, and receiving international recognition for his work. 7aam Arivu also proposes that the biomedical technology engineered by the ‘brown messiah,’ based on the scholarship of the ancients, should be exported by India to help the rest of the world providing scientific leadership just as it apparently did in late antiquity.

Billa II

While the images assembled in the movies thus far address the sense of impending global catastrophe in their diegesis, conspicuously foregrounding the role of the ‘brown messiah’ as savior, some leave open the possibility without being brazen about it. Looking at the casting of the gangster film Billa II: The Beginning (Dir. Chakri Toleti, 2012), the nationalist drive is latent. By transposing gangster film clichés on the grid of international relations, a hermeneutic reading of Billa II reveals a hawkish foreign policy manifesto. In order to become a great power, India must act opportunistically to make the best of the new world disorder to acquire wealth, aggrandize territory, intimidate neighbors, threaten hostile states, and create a Pax Indica solely for India’s self-interest. Billa II also derides the older paradigms of internationalism based on universal brotherhood, and non-violent pacifism, associated with Gandhi and Nehru, as naïve, and anachronistic.

Read against the grain, the gangster film Billa II is an ultranationalist allegory. Inspired by Scarface (Dir. Oliver Stone, 1983), Billa II chronicles the criminal ascent of David Billa, a refugee of the Sri Lankan civil war, who becomes an international criminal dealing with drug smuggling, money laundering, and the illegal arms trade. Lacking the distinctive accent of the indigenous Tamil, David Billa appears to be a Tamil of Indian origin in Sri Lanka, the child of Indian immigrants in the country. Forced out by civil strife, he returns to India, grows from a local thug to the lieutenant of a kingpin in India, and eventually rises to become the biggest gangster in the subcontinent, wherein he finally establishes himself in transnational crime networks.

Functioning as a prequel to Billa (Dir. Vishnuvardhan, 2007) and the latest remake of the highly successful gangster series inaugurated by Bollywood’s Don (Dir. Chandra Barot, 1978), Bila II was intended to be darker, grittier, and more graphic in its portrayal of India’s underworld than any prior remakes. However, strip away the razzmatazz, and the beeline for Billa II racial politics may very well be. Paunchy, scruffy, grungy Tamil hero is pursued by Malayalee beauty, outsmarts the Telugu capitalist, easily kills multiple East Asian thugs, nails a Brazilian model, annihilates competition from European and African crime lords, and reserves the best action to take on the North Indian gangster, who betrays him, and defeats the head of the Russian mafia to become an international kingpin. The intricate constellation of multiethnic stars, with local and foreign identities diegetically and extra-textually, makes possible a further realist reading of the narrative, and our location of the ‘brown messiah’ in this mix.

It appears that the ethical paradigms in Billa II are rearranged for good — fair is foul and foul is fair in our dystopian present reality. The film aligns its gangster protagonist on the other side of the moral perimeter. David Billa bears some of the characteristics of screen villains from five decades ago; defying the moral-cultural codes established for Tamil action heroes. Yet, in comparison to the rest of the characters in an underworld described in one song in the soundtrack as akin to perdition, David Billa’s courageous drive postures him as a superior warrior, and therefore worthy of our cheers. His unflinching protection of those who subordinate themselves to his authority is another redeeming quality of an otherwise blood-soaked messiah. When he annihilates his enemies in an orgy of violence without hesitation, the audience is privy to the massacre because the scum of the earth are wiped out.

The symbolism is indicative. Victory, in multiple shootouts, outwrestling bigger athletic foes, prompt in vengeance, and ascendancy in the power structures of the narrative, is an unapologetic show of muscular nationalism through warfare. Fetishizing violence in Billa II is an extended metonymy for military assertion, the only means by which the Indian nation-state can achieve paramount position in the cutthroat world of international relations. Acting as a foil, the only morally sound individual in Billa II is David Billa’s elder sister who asks him: “Why do you carry a gun, when you should be carrying a Bible?” However, her voice is drowned out by the sound of gunfights and explosions throughout the film. Moreover, she is ill and paralyzed, and meets a quick end early into the story.

The suggestion is uncomplicated: in a vicious social darwinistic world, there is no room for the saints or the pacifists. Reiterating the philosophy of most of the aforementioned films, and especially Vishwaroopam, Billa II advocates that only the ‘brown messiah’ with his almost superhuman strength, irreverence for legal procedure, dedication to defend those who seek his guardianship, and unequivocal willingness to take on a terrifying form to annihilate global ‘evils’ can stop the cataclysms that confront humanity.

However, none of the visions in the recent Tamil action-masala films are accurate, nor do they reflect the thinking of India’s policy makers. India’s foreign policy has been marked by cautious self-interest. With the same number of Foreign Service staff as tiny Singapore, Pax Indica is at best aspirational. As The Economist bemoans in the language of the action-masala genre: “India is still punching well below its weight in foreign affairs.” In its most recent report about India abroad two years ago, the analysis is that the foreign policy apparatus that guides India abroad is cautious and cumbersome, i.e., in real life there are no Major Wizams, Captain Jagdishs, or supercop Duraisingams, to project Indian power beyond its borders [“India Abroad: No frills”, The Economist, 29th September 2012]. One official is quoted by the newspaper as saying “We run a no-frills policy… We’re not trying to cut a grand figure abroad, it’s a realist approach.”

The gap between fantasy and reality appears to be vast and insurmountable at present. Moreover, when domestic politics remains shambolic — secessionist movements, economic slowdown, a third of the population in poverty, widespread crime and corruption — superpower ambitions remain laughable. India would certainly benefit from a more assertive and imaginative foreign policy, but only after it resolves its internal mess, and reorganizes its severely underequipped foreign department. In this sense, the Tamil action-masala genre has been far more creative than the Indian Foreign Service.

Forthcoming films like Ai (Dir. S.Shankar), Booloham (Dir. N.Kalyanakrishnan), and Vishwaroopam II (Dir. Kamalhaasan), seem set to continue the globalizing verve of the recent action-masala genre. Critically, for a film industry and genre often accused of being parochial, these recent developments show willingness on the part of some Tamil filmmakers to experiment with making Kollywood globally relevant [“Foreign film professionals find space in Tamil cinema”, M Suganth, The Times of India, 27th May 2013] As argued earlier, there were very material considerations for regenerating the genre, and the attempts have been profitable. Given the spread and the growth of the Tamil Diaspora around the world, especially in US, Europe, East Asia and even Africa, it only makes sense to appeal to a global audience with internationally relevant themes. Especially when Bollywood’s recent preoccupation is to mock South Indians and in particular Tamils [“Kollywood furious as Shahrukh’s Chennai Express makes a mockery of Tamils”, Kollytalk, 14th June 2013], the response by Kollywood, to focus on bigger ambitions, is laudable.